“Your goal, like mine, is to send every refugee to a safer place. Sound about right? Sadly, that won’t happen. Not now. Probably not ever. There’s not room, politically speaking. Not in any country…tens of millions worldwide….No matter how sincere a story sounds, or what it makes you feel, remember that tears don’t qualify as evidence. We need proof of origin, proof of trauma, proof of flight. That means source documents. Identity cards, medical records, pay stubs, death threats, even envelopes in which death threats were sent.” – Liaison, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

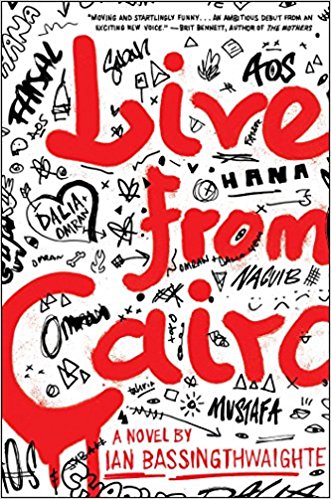

During his Fulbright Program in Egypt, beginning in 2009, debut novelist Ian Basingthwaighte had personal, daily contact with the horrors of displaced families – not just Egyptians but throughout the Middle East – as they flooded Cairo seeking help from the legal aid organization in which he worked helping refugees. Each day, he saw their scars and heard their stories as they left their homes, and often their families, to flee for their lives and the lives of their children. Unfortunately, getting to Cairo, often by foot, the goal of most of these refugees, does not guarantee the solutions they seek, no matter how much they are willing to give up. As the Liaison for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees points out in the opening quotation of this review, the size of the crisis is just too great. Setting his book in 2011, just after the overthrow of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak and the student revolt in Tahrir Square, which students hoped would change the nature of Egyptian government, Basingthwaighte creates a moving and absorbing novel of the human costs borne by innocent victims of the religious and political strife throughout the Middle East.

During his Fulbright Program in Egypt, beginning in 2009, debut novelist Ian Basingthwaighte had personal, daily contact with the horrors of displaced families – not just Egyptians but throughout the Middle East – as they flooded Cairo seeking help from the legal aid organization in which he worked helping refugees. Each day, he saw their scars and heard their stories as they left their homes, and often their families, to flee for their lives and the lives of their children. Unfortunately, getting to Cairo, often by foot, the goal of most of these refugees, does not guarantee the solutions they seek, no matter how much they are willing to give up. As the Liaison for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees points out in the opening quotation of this review, the size of the crisis is just too great. Setting his book in 2011, just after the overthrow of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak and the student revolt in Tahrir Square, which students hoped would change the nature of Egyptian government, Basingthwaighte creates a moving and absorbing novel of the human costs borne by innocent victims of the religious and political strife throughout the Middle East.

His characters represent several countries, all connected in some way with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Cairo. Hana, who opens the novel, has just started working for the UNHCR’s Refugee Affairs Department. She is an Iraqi-American whose father was blown up in Baghdad before she was born, and she is familiar with the issues of the refugees. Shortly after she arrives, she must act on the case of Dalia, a woman married to Omran, an Iraqi who helped the Americans build water mains in Baghdad until the tides of war changed and he had to escape. The Americans provided him with a visa because of his work for them, but Dalia did not qualify. After persuading her husband to leave, naively promising to follow him soon, she has come to Cairo to get a visa to join her husband, who is now waiting impatiently in Boston. Helping Dalia is an American immigration lawyer named Charlie who has been working for a legal aid society since 2007, and he has become somewhat jaded by the hopeless issues he faces daily. It is his secret love for Dalia which keeps him going now. Aos, an Egyptian, his translator, tries to live by the rules, but he yields to his feelings at night to continue protesting in Tahrir Square.

His characters represent several countries, all connected in some way with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Cairo. Hana, who opens the novel, has just started working for the UNHCR’s Refugee Affairs Department. She is an Iraqi-American whose father was blown up in Baghdad before she was born, and she is familiar with the issues of the refugees. Shortly after she arrives, she must act on the case of Dalia, a woman married to Omran, an Iraqi who helped the Americans build water mains in Baghdad until the tides of war changed and he had to escape. The Americans provided him with a visa because of his work for them, but Dalia did not qualify. After persuading her husband to leave, naively promising to follow him soon, she has come to Cairo to get a visa to join her husband, who is now waiting impatiently in Boston. Helping Dalia is an American immigration lawyer named Charlie who has been working for a legal aid society since 2007, and he has become somewhat jaded by the hopeless issues he faces daily. It is his secret love for Dalia which keeps him going now. Aos, an Egyptian, his translator, tries to live by the rules, but he yields to his feelings at night to continue protesting in Tahrir Square.

Hana, Charlie, Dalia, and Aos represent different aspects of the same refugee crisis – lively characters whose motivations become increasingly complex as they interact and as the points of view of each chapter rotate among them. Shortly after Hana starts work and has an orientation by Margret, her boss, Hana must decide on the case of Dalia. Margret has already decided that since the paper work proving Dalia’s marriage to Omran does not exist and because there is no proof, either, of the abuse Dalia has faced in her attempts to get to Cairo to apply for refugee status, that she cannot legally approve Dalia’s application. Charlie, Dalia’s lawyer, is horrified, and he is desperate to help Dalia. Though Hana has originally agreed with Margret, she later realizes that Dalia has been so seriously abused on her way to Cairo that she simply cannot bear to speak about those issues, which might, in fact, make her eligible for the visa she so desperately desires. Eventually, Charlie comes up with an illegal plan that might help Dalia, and he draws in Hana to be part of this plan. It will take a great deal of money if Dalia is to acquire the papers she needs, and though no one has that money, Charlie is not giving up. Helping Dalia has become the only thing in his life that has meaning.

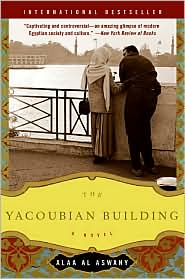

The Yacoubian Building by Alaa Al-Aswany, reviewed HERE:

Within this framework, the novel develops with excitement, at the same time that it is also sensitive to the very real, human issues involving the characters (and by extension, other refugees like Dalia). The characters’ anxieties and their stresses slowly build as Bassingthwaighte provides rich visual and atmospheric details which make Cairo come alive and their crises become even more affecting. He also broadens the scope by including many cultural references which often add irony to the narrative. Aos, Charlie’s translator, is frustrated with the fact that though Mubarak has been deposed, “Only the image of the regime has changed.” He took a chance by demonstrating at Tahrir Square, at one point, but he was captured and tortured in the basement of the Egyptian Museum, an irony which made him decide that “Next time he’d sacrifice himself.” He reconnects with a man from his school days at Cairo University, where together they had studied Alaa Al-Aswany’s The Yacoubian Building, a book of present day culture that has sold more copies than any other contemporary novel in Egypt, and he continues to stay in touch with him during a later crisis. Hana, by contrast, simply walks to the busy market at Khan el-Khalili when she needs a break, then sits and gazes at al-Fishawi, the historic cafe where Nobel Prize-winning author Naguib Mahfouz often spent his days writing in the Mirror Room, “beneath a giant Spanish mirror with lotus blossoms carved into the frame.”

El Fishawi cafe, at el-Khalili, where Naguib Mahfouz often wrote from his table in the Mirror Room. Review of Naguib Mahfouz books HERE.

Seemingly casual cultural references like these – to the Egyptian Museum, to Alaa Al-Aswany, and to Naguib Mahfouz (who wrote fifty novels) – broaden the focus of the novel beyond the short-term issue of Dalia’s visa and the refugee crisis, and links it to Egypt’s long cultural history. Other descriptive details expand the reader’s involvement, allowing him/her to picture every aspect of the action. When the climax occurs, it is worthy of the book – both heart-rending and cathartic. Dramatic and life-changing for all, it inspires resolution among the characters. A short Part IV takes place six months later, concluding the novel, and though it is a bit awkward structurally, it is necessary to resolve issues for the reader. Bassingthwaighte has created a big novel with important themes and information about a world crisis, within an intimate novel, which feels “live from Cairo” – a book in which real human beings do the best they can and with the best of intentions. Exciting, enlightening, important, and very human.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.booksonthecape.com/

The student uprising in Tahrir Square, from Jan. 25, 2011, – Feb. 11, 2011, culminating in the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak: http://arabspring-us-geopoliticalcodes.weebly.com/

The Yacoubian Building by Alaa Al-Aswany is reviewed on this site: http://marywhipplereviews.com

El-Fishawi cafe, where Nobel Prize winner Naguib Mahfouz often spent time writing in the Mirror Room: http://travel.nationalgeographic.com/

Portrait of Naguib Mahfouz: https://www.nobelprize.org/