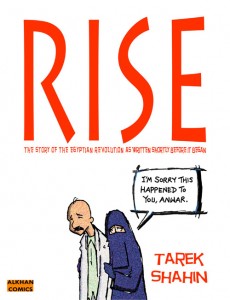

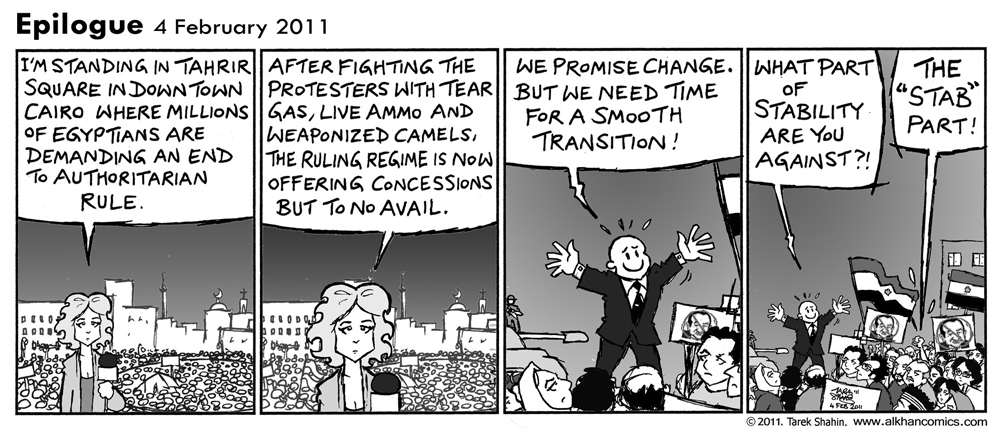

Many thanks to Tarek Shahin for granting an interview about his book RISE: the story of the Egyptian Revolution, a collection of satiric cartoons from the Daily News Egypt from April, 2008 – April 2010, in the lead-up to the Egyptian Revolution of January 25 – Feb. 11, 2011. I hope this interview will shed some light on what it is like to be a cartoonist during the tensions near the end of the Mubarak regime and how one finds humor in serious topics:

Q: It is clear that Omar, the newspaper publisher, is, in some ways, your alter-ego, and you are obviously having fun with him. Like Omar, you, too, have been in the financial services industry with jobs in both Cairo and London, so I’m going to ask the obvious: How much of yourself have you put into Omar? In what ways is he very different from you? And are you Egyptian, British, or a dual citizen?

Q: It is clear that Omar, the newspaper publisher, is, in some ways, your alter-ego, and you are obviously having fun with him. Like Omar, you, too, have been in the financial services industry with jobs in both Cairo and London, so I’m going to ask the obvious: How much of yourself have you put into Omar? In what ways is he very different from you? And are you Egyptian, British, or a dual citizen?

A: There’s a little of me in all the main characters and there’s a lot of Omar in me. And I am Egyptian.

Q. How did you go about getting a job in the newspaper business in Cairo? That must have been a “plum” position for a such a young cartoonist—or was it unique, a result of the cartoon itself and what it had to say?

A: The editor of The Daily News Egypt had been a fan of my cartoon blogging and had occasionally asked to publish my online editorial cartoons in the paper. When I pitched a daily character-driven comic strip to her, thankfully she was on board.

Q. Did you ever study drawing or have a cartoon strip before Al Khan?

A: I never studied drawing academically – my bachelor’s degree was in business finance and I followed that with an MBA. In university I wrote a comic strip in the weekly student paper, which was quite popular, if I may say so, and not without controversy. My mother is a remarkable oil painter, in her spare time, but I don’t know if that had a direct affect on my abilities as a cartoonist.

Q. And how did you manage to work in the investment business during the day and do cartoons at night? That sounds like more than a 12-hour day to me, and in two very different worlds.

A: With great difficulty.

Q. The cartoons are written in English but were originally published in Cairo. Is that because you were trying to attract a different audience from what you’d have attracted if you had published in Arabic? How would you describe the audience you did attract in Cairo?

A: I set out to reach an international audience because I was sick of the generalizations that people make about other peoples. I did fear I would alienate and lose many a potential Arabic-reading reader at home, but refreshingly I was surprised to gather many readers who are not fluent English speakers. Generally, the audience I gathered at home was the minority of people who gave a s— about something other than the damn football game. Very few people cared about politics and most were still averse to discussing socially sensitive issues like sex or sex crimes. What a difference two years make, now after the successful uprising in January 2011, everyone and their uncle wants to talk politics.

Q. I was really impressed by the variety of beliefs you managed to present with such good humor—Omar is a “liberal capitalist” who tries to see all sides of issues, though his ego and pragmatism sometimes get in his way; Nada is an extreme leftist, considered a communist by Omar; Anwar’s a conservative Muslim who uses the idea of taking other wives as a ploy to keep his wife (in niqab and burka) in check; Yunan is a Coptic Christian, whose views I haven’t found very often in Egyptian fiction, so that especially interested me. And the Big Falafel, the beggar, is obviously extremely intelligent, able to absorb mountains of information. Were you ever harassed for the points of view you presented so humorously (and often satirized) in the cartoon?

Q. I was really impressed by the variety of beliefs you managed to present with such good humor—Omar is a “liberal capitalist” who tries to see all sides of issues, though his ego and pragmatism sometimes get in his way; Nada is an extreme leftist, considered a communist by Omar; Anwar’s a conservative Muslim who uses the idea of taking other wives as a ploy to keep his wife (in niqab and burka) in check; Yunan is a Coptic Christian, whose views I haven’t found very often in Egyptian fiction, so that especially interested me. And the Big Falafel, the beggar, is obviously extremely intelligent, able to absorb mountains of information. Were you ever harassed for the points of view you presented so humorously (and often satirized) in the cartoon?

A: Yes. Al Khan is acknowledged to be controversial, to say the least, when it comes to social topics and edgy at the time when it came to jabs at the now ousted former regime. Whether it was ahead of its time in foreseeing – or wishfully thinking – that a revolution of this magnitude would occur is for the reader of ‘Rise’ (the Al Khan collection) to decide.

Q. You certainly do not shy away from “hot topics.” Did you get any negative feedback at all (from the public or from the newspaper itself) when you tackled topics like the belief that rape victims “ask for it” if they are not covered; that rape is not a serious “crime”; that marriages between cousins, not unusual, might produce a “three-eyed baby”; that multiple wives are good for the family; that some gynecologists have made a lucrative career from the surgical “repair” of young girls who have been raped; and that genital mutilation of women is an advantage for their husbands?

A: Also yes. From both the public and the publishers of the newspaper who would yell at Rania, the editor, but never from Rania herself. She gave me all the freedom.

Q. Which issues drew the most attention? Sociological issues like the ones in the previous question or the host of topical political issues which you also address? And how did you decide where to draw the line on what to depict as absurd?

A: I use subtlety as an artist for comedic effect. That’s my style. As it happens subtlety leads to self-policing in that I always chose to be controversial without being vulgar or if one of the characters uses vulgarity, I made sure the reader would not walk away feeling the words were out of character or forced or that I was doing it only for shock value.

Q. Your strips were running in Cairo at the same time as the essays of Alaa Al Aswany, who was writing in the opposition press (His new book, published recently by American University of Cairo Press, is ON THE STATE OF EGYPT: A Novelist’s Provocative Reflections) Did writers, cartoonists, photographers, and journalists involved with the opposition have any organized way to communicate with each other, or were you all working independently for the same goal?

A: Oh yes, most of us writers and bloggers knew each other and became friends – which at times was awkward because most of the bloggers wrote anonymously (they have since revealed themselves in the wake of the January 2011 uprising). Mind you, there was also a lot of friction amongst us because although we were vocally pro-democracy, we had very different world views (classic left versus right) – that I think becomes very clear to the reader of ‘Rise’ because it is only towards the end that the characters not only were able to rise above their fears but also above their differences in order to come together for change.

Q. I liked the way you wound up the series in April, 2010, as it provides a sense of resolution regarding the characters. Is there any possibility of your restarting another series, post-revolution, to keep the public up to date about what’s happening in the wake of the revolution?

A: I’m now working primarily on a self-contained graphic novel which is not about politics (or is it?), and in terms of restarting the series – I am waiting for the dust to settle. Al Khan was cool in part because it was written before it was cool to write about the sociopolitical. Rest assured, as a writer I will continue to say what most people don’t want to hear.

And I’ll be one of the first to look for it! Best wishes for much success with it! Mary

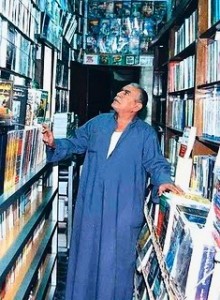

POSTSCRIPT: Q. At one point during the series, I was really touched by your homage to Hajj Madbuli, who started out selling magazines on the street, and eventually became Egypt’s biggest publisher. I just found a similar post honoring him in the Kirmalak blogspot: http://kirmalak.blogspot.com What factors made it possible for Hajj Madbuli to propel himself into this position? And how would you describe the status of independent bookstores around Cairo?

A: I am not an authority on Hajj Madbuli’s biography, but in as far as character has anything to do with how he got to be in his position, let me tell you a story. I’m a 19-year old undergrad in Cairo responsible for fundraising for the Cairo Model United Nations (and Model Arab League), an  extracurricular activity. Our job was to go door to door to business owners and corporate CEOs to raise money for the student conference in return for advertising space on our university campus. After signing several such contracts as well as getting many more rejections, I walk into Madbuli’s flagship bookstore (incidentally adjacent to Tahrir Square) and ask for the store manager. Instead, as it happens, the man himself is there. I do the pitch: Madbuli (the business) helps sponsor the conference and in return we offer ad space for Madbuli. Hajj Madbuli takes a roll of cash out of his pocket and puts it in my hand. We’d never met before. I ask him if he’d like to know more about the on-campus advertising package we offer in return for his sponsorship. “The only return,” he said, “is that one day I will pass by a big building – a company, a hospital, a law office – and the sign at the entrance will read your name.” I would meet him another time many years later at the Cairo book festival but of course he was surrounded by people who wanted to shake his hand. He died the following year.

extracurricular activity. Our job was to go door to door to business owners and corporate CEOs to raise money for the student conference in return for advertising space on our university campus. After signing several such contracts as well as getting many more rejections, I walk into Madbuli’s flagship bookstore (incidentally adjacent to Tahrir Square) and ask for the store manager. Instead, as it happens, the man himself is there. I do the pitch: Madbuli (the business) helps sponsor the conference and in return we offer ad space for Madbuli. Hajj Madbuli takes a roll of cash out of his pocket and puts it in my hand. We’d never met before. I ask him if he’d like to know more about the on-campus advertising package we offer in return for his sponsorship. “The only return,” he said, “is that one day I will pass by a big building – a company, a hospital, a law office – and the sign at the entrance will read your name.” I would meet him another time many years later at the Cairo book festival but of course he was surrounded by people who wanted to shake his hand. He died the following year.

By the way, it might interest you to know that the blog you reference, Kirmalak.blogspot.com, belongs to my cousin Khaled. Freaky coincidence!

On the second part of your question, I think independent bookstores have an opportunity in the medium term as many people feel that they were too docile before the uprising and are keen to become better informed – but of course, globally, I don’t know how bookstores in general will cope with an increasingly e-world.

Graphics, in order: All of the graphics were provided by Tarek Shahin, at my request, with the exception of the photo of Hajj Madbuli, which appears on http://kirmalak.blogspot.com

The cartoon of the main characters show (top row) Omar and Nada, and (bottom row) the Big Falafel, Yunan, and Anwar.

In the photo of Tahrir Square, the author is seen in the center, holding the blue water bottle.

Link to review of RISE: The Story of the Egyptian Revolution…