“This country slowly but surely is going to explode…South Africa’s on the way up, and we’re on the way down. Bread’s become a luxury, and what do [our leaders] go and do? Blow a stack…on luxury Mercs for ministers; Bob [Mugabe]’s so out of touch, with his trips and that chick of his, he knows shit all…I hate to say this, but no one starved under [Ian] Smith.”

Set in Zimbabw e from the early 1980s through the late 1990s, Irene Sabatini’s debut novel focuses on the racial conflicts which underlie the history of Zimbabwe, formerly Rhodesia, which was under British rule for a hundred years before being granted independence in 1980. Independence was not a clear-cut victory for one side over another, however, as many factions contributed to the victory of the majority black population over their white rulers. Using the love story of a white Rhodesian man and a mixed race, “colored” woman, over the course of almost twenty years, Sabatini traces the country’s deterioration economically, culturally, and socially, under President Robert “Bob” Mugabe, who is still president of Zimbabwe after more than thirty years.

e from the early 1980s through the late 1990s, Irene Sabatini’s debut novel focuses on the racial conflicts which underlie the history of Zimbabwe, formerly Rhodesia, which was under British rule for a hundred years before being granted independence in 1980. Independence was not a clear-cut victory for one side over another, however, as many factions contributed to the victory of the majority black population over their white rulers. Using the love story of a white Rhodesian man and a mixed race, “colored” woman, over the course of almost twenty years, Sabatini traces the country’s deterioration economically, culturally, and socially, under President Robert “Bob” Mugabe, who is still president of Zimbabwe after more than thirty years.

The narrative begins in the early 1980s, when Lindiwe Bishop, a young teen, is shocked by a terrible crime which takes place next door. The McKenzies’ house has been torched, and the stepmother and the father of seventeen-year-old Ian McKenzie have both been burned to death. An unidentified woman has also been seriously burned, taken to the hospital with life-threatening injuries, and young Ian has been arrested after confessing to the crime. The McKenzies are the “last remaining whites on the street” where Lindiwe lives, and Ian has been a casual friend who has visited her house numerous times. When Lindiwe’s dog finds a lighter in the bushes near the McKenzie house, she keeps it hidden for fear of what it might mean regarding Ian.

Sabatini quickly establishes the human qualities of her characters, along with their resentments and jealousies as she recreates the social milieu of Bulawayo in Zimbabwe. Lindiwe, light-skinned, is one of the few mixed-race children in her nearly all-white school, and she suffers from the mockery and name-calling of her white peers, her mother avoiding the  problems by allowing herself to be regarded as one of the maids when she visits the school. Lindiwe is symbolic of much of the country in that she has learned to tolerate even gross abuses in order to survive. With no sense that she has any power, she has a limited, childish view of the country’s political situation, and her impressions of the various rebel movements, some of which continue to fight for their own special goals in areas all around her, are equally limited. After Ian is released from prison less than two years later, she and he form a tight bond, each regarding the other as the only real friend.

problems by allowing herself to be regarded as one of the maids when she visits the school. Lindiwe is symbolic of much of the country in that she has learned to tolerate even gross abuses in order to survive. With no sense that she has any power, she has a limited, childish view of the country’s political situation, and her impressions of the various rebel movements, some of which continue to fight for their own special goals in areas all around her, are equally limited. After Ian is released from prison less than two years later, she and he form a tight bond, each regarding the other as the only real friend.

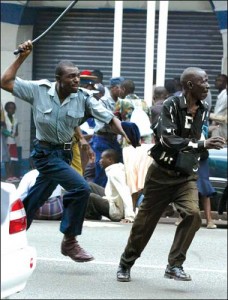

As time moves forward, Sabatini shows the country’s deterioration in terms of the effects on her main characters and on the country at large. Skipping significant chunks of time in Part II, she reintroduces Lindiwe seven years later, in the early 1990s, as a graduate student in Harare. Ian is a photojournalist, working mostly in South Africa, when he returns to Zimbabwe. Throughout, Sabatini keeps the reader abreast of the changing political climate, the social unrest and the riots, the increasing racial violence—this time against whites by young blacks—and the precarious position of those who are “colored.”

Burning farm of Mike Campbell and Ben Freeth

Ultimately, Sabatini creates a vibrant novel in which she explores the downward spiral of Zimbabwe over the past nearly-thirty years, despite the hopes of much of the population. The corruption, the intolerance, the sense of entitlement by soldiers and militias who have fought against the white establishment, the economic hardships, the violence of the army and police against those who oppose those currently in power, and the complications created by South Africa and other African countries who may fear the possible effects of a free Zimbabwe are all explored in detail, especially as they affect Lindiwe, Ian, and their friends. Though the novel is uneven and takes some time to establish its themes and its direction at the beginning, Sabatini gains her footing for the last half and creates well developed characters facing challenging and emotionally wrenching problems, not always of their own making.

Mike Campbell and Ben Freeth in front of burned farm

As the characters grow over time, the reader develops empathy for them, seeing them as complete human beings, not as representatives of any particular racial or political point of view. Though melodrama plays its part in the evolution of the plot, Sabatini uses it to connect her characters to the themes and to show the human costs of the racial divide which has dominated African life for so long. By working actively to “keep it simple,” Sabatini has created a memorable picture of life in Zimbabwe since its independence, a picture which does not lose its power in complicated details.

Robert Mugabe on 85th birthday

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from her publisher’s site: www.hachettebookgroup.com

The street violence in Harare is shown on www.thenewblackmagazine.com.

The burning family farm above “belongs” to Mike Campbell and Ben Freeth (shown in the next photo). http://www.dailymail.co.uk. Campbell, Freeth, and Freeth’s wife were beaten for nine hours, suffering 14 broken bones among them when they refused to give up willingly.

In the final photo strongman Robert Mugabe celebrates his 85th birthday, an event for which his supporters reportedly donated $400,000. http://www.abc.net.au

The story of Campbell and Freeth became the subject of a documentary which won Best Documentary of 2010 at the British independent Film Awards: The very dramatic trailer may be seen here: