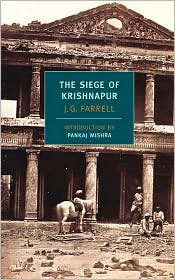

Note: In 1973, this novel was WINNER of the Booker Prize for fiction.

“What a lot of Indian life was unavailable to Englishmen.”

The bloody Siege of Krishn apur in 1857 is the pivot around which the action revolves in this Booker Prize-winning novel by J. G. Farrell, but Farrell’s focus is less on Krishnapur and the siege than it is on the attitudes and beliefs of the English colonizers who made that siege an inevitability. He puts these empire-builders under the microscope, then skewers their arrogant and superior attitudes with the rapier of his wit, subjecting them to satire and juxtaposing them and their narrowly focused lives against the realities of the world around them. Remarkably, he does this with enough subtlety that we can recognize his characters as individuals, rather than total stereotypes, at the same time that we see their absurdity and recognize the damage they have done in their zeal to spread their “superior” culture.

apur in 1857 is the pivot around which the action revolves in this Booker Prize-winning novel by J. G. Farrell, but Farrell’s focus is less on Krishnapur and the siege than it is on the attitudes and beliefs of the English colonizers who made that siege an inevitability. He puts these empire-builders under the microscope, then skewers their arrogant and superior attitudes with the rapier of his wit, subjecting them to satire and juxtaposing them and their narrowly focused lives against the realities of the world around them. Remarkably, he does this with enough subtlety that we can recognize his characters as individuals, rather than total stereotypes, at the same time that we see their absurdity and recognize the damage they have done in their zeal to spread their “superior” culture.

From the opening pages, Farrell builds suspense as the English colony ignores reports of unrest in Barrackpur, Berhampur, and Meerut. The flirtations of the single women, the amorous attentions of the young men, the boorish and insensitive behavior of the officials, the gossipy whispering of their wives, and the unrelenting efforts to maintain the same society they enjoyed at home–with tea parties, poetry readings, and dances–all attest to their degree of isolation from the world around them. When violence breaks out in Krishnapur and all the inhabitants take refuge in the colonial Residence, Farrell turns it into a microcosm which illuminates their misplaced values and goals as they interact with each other and face dangers from without–and from within. The siege continues for more than three months, with bloodshed, disease, starvation, lack of water and medicine, and the summer weather taking their toll.

Farrell’s dark humor is unparalleled. Using irony, understatement, and a sense of the absurd, he conveys his disapproval of colonialism without resorting to the harshness of polemics. By concentrating exclusively on the English in the Residence and not on India’s local population (ironically reflecting the approach of the colonizers themselves), he makes their behavior appear ridiculous in its own right, rather than ridiculous in comparison to other cultures. Mr. Rayne, the Opium Agent, calls the sale of opium, “progress.” The Padre cannot understand why the Bible was originally written in an obscure language like Hebrew, rather than English, which is “spoken in every corner of every continent.” A dying man offering up his last, heartfelt prayer is told by the Magistrate, “Yes, yes, to be sure, don’t worry about it.” The heads from a collection of small sculptures of the “great minds of Europe” are used as deadly explosives when shot becomes scarce.

Through his precise imagery, his acute eye for memorable and revealing details, his unerring ear for dialogue, his ability to maintain pace and suspense, and his humor, Farrell creates a historical novel with the enduring qualities which make it as relevant today as it was when published more than thirty years ago.

Also reviewed here: TROUBLES and THE SINGAPORE GRIP