Note: This book was a FINALIST for the National Book Award for Fiction, 2018.

“Not long after the incident…my mother left us, and later she divorced my father….My father worshipped my mother, [and] after she left, he became bitter. One day he complained to me that she wasn’t really gone at all, that she was much too wicked for such a mercy. She was still there, he said, stuck in him: a froth in the veins, a disease of the blood. That’s how I began to think of her, as a sickness, a betrayal on the cellular level.”—Ben, in “No More Than a Bubble.”

Jamel Brinkley, author of this extraordinary debut collection of stories, is much more than “a lucky man” in having this collection published by Graywolf, one of the most respected literary publishing houses in the country. Brinkley’s literary talents and his insights into people – all kinds of people of various backgrounds and ages – kept me spellbound for the entire time I spent reading and rereading these stories. I am not young, black, male, or a city dweller, as these characters are. I have not experienced (or do not remember) most of the kinds of events which Brinkley’s characters experience as normal – growing up in a broken home, having few resources for dealing with the turmoil of the teen years, struggling with responsibilities which would be challenging even for an adult, and living a life in which “betrayal on the cellular level” is complicated by surprising naivete regarding love and sex, expectations and reality, and issues of identity and reputation. Still, as the young male characters of the nine stories here live their lives as well as they can, given their ages and limitations, they achieve a kind of universality which cannot help but touch the heart of the reader as s/he connects with these characters on a deeply personal level.

The opening story, “No More Than a Bubble,” from which the opening quotation here has been taken, has a simple enough beginning, as two young college students, Ben and Claudius, attend a house party in New York given by a couple of Harvard grads. “The main difference between a house party in Brooklyn and a college party uptown was that on campus you were just practicing. You could half-ass it or go extra hard, either play the wall or go balls-out booty hound, and there would be no actual stakes, no real edge to the consequences.” They soon meet two women from Hunter College, but the women are a bit older than they, and it is obvious from the dialogue that Ben and Claudius are overmatched. Throughout this episode and its consequences, Ben keeps flashing back to emotionally intense memories of his parents and their marriage. Eventually, when the party is over, the women try to leave on their bikes, but are unable to balance, and Ben and Claudius walk them home to Brooklyn. There Ben discovers that not only are the women different from what he had thought, but so is Claudius, a life-changing moment.

The opening story, “No More Than a Bubble,” from which the opening quotation here has been taken, has a simple enough beginning, as two young college students, Ben and Claudius, attend a house party in New York given by a couple of Harvard grads. “The main difference between a house party in Brooklyn and a college party uptown was that on campus you were just practicing. You could half-ass it or go extra hard, either play the wall or go balls-out booty hound, and there would be no actual stakes, no real edge to the consequences.” They soon meet two women from Hunter College, but the women are a bit older than they, and it is obvious from the dialogue that Ben and Claudius are overmatched. Throughout this episode and its consequences, Ben keeps flashing back to emotionally intense memories of his parents and their marriage. Eventually, when the party is over, the women try to leave on their bikes, but are unable to balance, and Ben and Claudius walk them home to Brooklyn. There Ben discovers that not only are the women different from what he had thought, but so is Claudius, a life-changing moment.

“J’ouvert, 1996” features Ty, an innocent seventeen-year-old whose only desire is to have fifteen dollars so he can go to a barbershop to get a professional haircut at the place where his now-departed father used to go. He has little control over his life, however, as he must take care of his eleven-year-old brother Omari during the summer when school is out. His brother, who clearly has some problems, insists on wearing a rubber mask of an owl and “smoking” a candy cigarette whenever he is outside, and when his mother sends the boys out one night so that she and her boyfriend can have some privacy, Ty and Omari take off. The boys are bullied, Ty loses a gift from his departed father, and Omari escapes into his imagination. Ty eventually decides to go to J’ouvert, a Caribbean carnival which starts very late that night, a place where both he and Omari learn important things about themselves and the world.

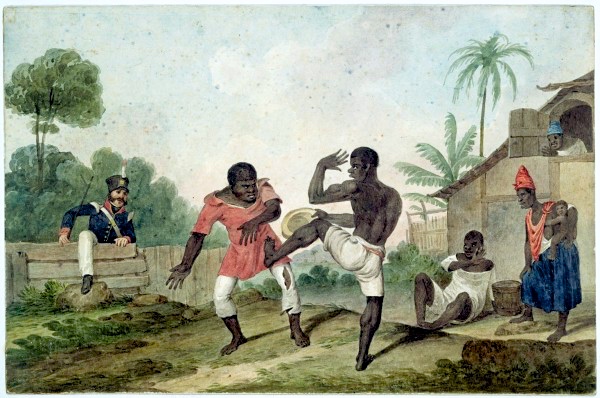

Capoeira angola by August Earle, 1824.

These two stories – one of a college boy and one of a much younger boy and his eleven-year-old brother – show Brinkley’s ability to capture the thinking of these youths as they face real events associated with maturing. In “Everything the Mouth Eats,” he shows his ability to make an adult character equally intriguing. Main character Eric describes himself as a “lost” adjunct professor at a Manhattan college, and he admits he “hadn’t had a talk – a real talk” with his younger brother Carlos in many years. The two brothers have both experienced the same kind of abuse, but Carlos, unemployed and sometimes in trouble, has recently managed to get his life under some control through his serious study of capoeira, an Afro-Brazilian martial art which includes acrobatics, dance, and music. Eric, Carlos, Carlos’s girlfriend, and their young daughter are driving to Virginia for a conference and demonstrations of capoeira, and Carlos’s girlfriend has confided to Eric that Carlos really needs him now. Eventually, the performances of capoeira in which they both participate open new lanes of communication and purpose.

Other stories focus on different subjects. “I Happy Am” tells of a young boy at summer camp who takes a field trip to a wealthy estate to enjoy the day swimming, only to discover that the estate is not that much different from what he has at home, and the hostess is not very different from his mother. “A Family” concerns a man who has served twelve years in prison and who is now faced with the possibility of becoming a lover to his deceased best friend’s wife. “Wolf and Rhonda” offers the reader a female character whose hard life and possible relationship with Wolf turn the story on its head. “Clifton’s Place” is a story of aging and change, and this is the one place where obvious symbolism occurs as two men involved with the same woman, walk through Brooklyn’s Fort Green Park, where the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument serves as a memorial to the American soldiers who died on British prison ships anchored in the East River during the Revolutionary War.

Focusing on the past and its importance in our lives, and masculinity and what it means in the present, Brinkley develops sub-themes of guilt and innocence, assertiveness and shyness, independence and isolation, desire and frustration, and power and subservience, all within nine compressed and dramatic stories which will awe most readers.

Photos. The author’s photo appears on: http://www.startribune.com/

The author’s photo perfectly reflects his style throughout. He is looking directly at the reader, with no pretense, hiding nothing. http://www.startribune.com/

Photo of the L’ouvert celebrations by Stephanie Keith, Getty Images. https://observer.com/

A painting of capoeira angola activity by August Early in Brazil in 1824. https://en.wikipedia.org

The Prison Ship Martyrs Monument in Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn. https://www.dnainfo.com The inscription on the monument reads: In the name of the spirits of the departed free, sacred to the memory of that portion of American seamen, soldiers & citizens who perished in the cause of liberty & their country on board the prison ships of the British (during the Revolutionary War) at the Wall-about. This is the corner stone of the vault which contains their relics. Erected by the Tammany Society or Columbian Order of the City of New York. The ground for which was bestowed by John Jackson, Nassau Island, season of blossoms, year of discovery, the 316th, of the institution the 19th, and of American Independence the 32nd, April the 6th, 1808.