“ [I] have the occasional white night in which a chef’s panic about running out of thyme somehow takes on a disproportionate and dismal urgency. I’m also reduced to compulsively playing with words¸ which appear in my fevered mind as large white letters on a blackboard that re-shuffle themselves unstoppably. The anagrams take on an aura of spurious significance that fades even as dawn strengthens outside. Thus Lyme Regis is turned to Grey Slime…”

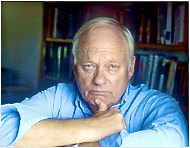

Having won the Whitbread Award in 1989 for Gerontius, a literary novel about composer Sir Edward Elgar, James Hamilton-Paterson has written most recently in a completely different vein – three wild, off-the-wall novels starring Gerald Samper, an aesthete with a love for gourmet food, clothing, and cutting edge social commentary. Samper is, however, something of an ass, a man so self-absorbed and so convinced of the importance of his (as yet undiscovered) “mission” in life that he “lurches from crisis to crisis,” never pausing for reflection. Despite these unsympathetic qualities, however, Samper cannot help but amuse and intrigue readers as he involves us in his whirlwind activities and invites us to join him on the rollercoaster of his life.

Having won the Whitbread Award in 1989 for Gerontius, a literary novel about composer Sir Edward Elgar, James Hamilton-Paterson has written most recently in a completely different vein – three wild, off-the-wall novels starring Gerald Samper, an aesthete with a love for gourmet food, clothing, and cutting edge social commentary. Samper is, however, something of an ass, a man so self-absorbed and so convinced of the importance of his (as yet undiscovered) “mission” in life that he “lurches from crisis to crisis,” never pausing for reflection. Despite these unsympathetic qualities, however, Samper cannot help but amuse and intrigue readers as he involves us in his whirlwind activities and invites us to join him on the rollercoaster of his life.

In the first of the three Gerald Samper novels, Cooking with Fernet Branca (2004), Hamilton-Paterson introduces the reader to Samper and his friends and acquaintances (and those with whom he refuses to associate), creating a novel that is bursting with life and filled with puns, word play, and humor – while he also describes a series of Samper’s repulsive “gourmet” recipes. (Jack Russell Pate and Smoked Cat with Fernet Branca Sauce are particularly memorable). In Amazing Disgrace (2006), he continues the story of Samper, who is supporting himself by writing books about sports and media figures whom he not-so-secretly scorns, most recently Millie Cleat, a one-armed yachtswoman, who loves the spotlight. When Millie has a fatal accident on camera in Australia, Samper regards it as a blessing, since it  permanently removes Millie from his life, leads to astonishing sales of his book, and results in a high price for the movie rights. At the end of Amazing Disgrace, however, Samper has his own misfortune – during his 50th birthday celebration with friends at his home on a Tuscany hillside, an earthquake sends his house plummeting down the hillside, ending as a pile of rubble.

permanently removes Millie from his life, leads to astonishing sales of his book, and results in a high price for the movie rights. At the end of Amazing Disgrace, however, Samper has his own misfortune – during his 50th birthday celebration with friends at his home on a Tuscany hillside, an earthquake sends his house plummeting down the hillside, ending as a pile of rubble.

Rancid Pansies continues Samper’s story (though it is not necessary to have read the other wild works). Even “in exile” in someone else’s house, he has continued his “gourmet” experiments with unusual ingredients. Hedgerow broth with gently seethed owl pellets, liver smoothies, and Mice Krispies Vol-au-Vent, become the basis for a disastrous meal at an English country house Samper visits after the Tuscany house debacle, giving new meaning to the term “throwing a dinner.” (We should probably  be grateful that he did not embrace cannibalism when he contemplated the nutritional slogan to “Eat your Greens.”) And a facetious remark Samper made while being evacuated from the site of his now-vanished home – that Princess Diana had appeared in a vision and warned him and his guests to abandon the house just seconds before disaster struck – has led to hordes of pilgrims descending on his destroyed property. A makeshift shrine there soon becomes a grotto, and the local mayor and the comune see the tourist potential for marketing the site.

be grateful that he did not embrace cannibalism when he contemplated the nutritional slogan to “Eat your Greens.”) And a facetious remark Samper made while being evacuated from the site of his now-vanished home – that Princess Diana had appeared in a vision and warned him and his guests to abandon the house just seconds before disaster struck – has led to hordes of pilgrims descending on his destroyed property. A makeshift shrine there soon becomes a grotto, and the local mayor and the comune see the tourist potential for marketing the site.

Marta Priskil (the anglicized name used by the Voynovian composer and former nemesis of Samper, who lives in the house next door) can no longer work at home because of the noise and distraction. At Samper’s urging, she sells her property and buys another house, while also agreeing to work with Samper to create an opera about Princess Diana, the royal family, and the movement to declare her a saint.

Hamilton-Paterson is too good a writer to rely on low humor like the disgusting food conceit for the entire novel. He delights in poking fun at British pretentions, British life, and even the royal family. His satire takes on added dimensions as Samper travels and comments about the differences between Italy, where he lives, and England where his business interests, and many of his friends, reside. Italy, too, comes in for his satire, especially as Samper must deal with local politics and the permitting process to be able to restore a house he intends to buy.

A great punster, lover of word play, and creator of wild anagrams, including the title of this book (which is also the name of Samper’s opera), Samper keeps the reader constantly in awe at his never flagging cleverness, even as the “plot,” such as it is, explodes in several different directions at  once. His startling use of unique similes and metaphors (elderly, retired nuns described as “midget creatures like worn-out bats,” for example) make Samper’s commentary and opinions about his surroundings a delight to read. Providing perspective on Samper’s life is his British companion Adrian, whose regular e-mails at the end of each chapter update a friend on Gerald’s latest (absurd) fiascos.

once. His startling use of unique similes and metaphors (elderly, retired nuns described as “midget creatures like worn-out bats,” for example) make Samper’s commentary and opinions about his surroundings a delight to read. Providing perspective on Samper’s life is his British companion Adrian, whose regular e-mails at the end of each chapter update a friend on Gerald’s latest (absurd) fiascos.

When the opera created by Samper and Marta finally has its premiere in England, Hamilton-Paterson gives new meaning to the term “opera buffa,” as the evening turns so hilariously absurd that no pretense at seriousness can be maintained. The opera’s libretto is clever and blackly humorous, the satire of the royals is wicked, and the results are unforgettable. Impossible to categorize, this novel is a series of loosely connected episodes, each more absurd than the previous one, with dark humor, satire, and word play running riot, and the reader hanging on in delight for the wild ride.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Canarsa is from http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com

Vols-au-vent appear on http://persnicketypalate.com

The landslide appear on http://www.kalimpong.info

The picture of Princess Diana is from http://www.rumormillnews.com