Note: This novel was WINNER of the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize for 2015 and WINNER of Germany’s 2014 Hans Falada Prize.

“If her grandmother had left for the Vienna Woods just half an hour later; …or if [she] who was so eager to cast her life aside had not…taken a right turn from Babenberger Strasse onto Opernring, where she coincidentally encountered her own death in the form of a shabby young man; or if the fiancée of this shabby young man had not broken off their engagement; …or if the shabby young man’s father hadn’t left his Mauser pistol in the unlocked drawer; …then she would not have been thinking of [being] shot, but [instead] about…a dark painting inside the [nearby] museum.”

The above quotation is not really a spoiler, since this unusual novel features a cast of characters whose lives change constantly in response to the circumstances of their lives. Even death is not permanent. If the unnamed main character makes a bad choice and dies, usually through no fault of her own, German author Jenny Erpenbeck simply changes one or more of the conditions which brought about the character’s death and its terrible consequences to the family and retells her story. In fact, the unnamed main character here has five “deaths” in the novel’s five “books,” and other characters experience similar changes of fortune as the author examines the very nature of time, mortality, fate, coincidence, and the effects of a death or other terrible event on the people connected to that character. There is no heavenly hand, no higher deity, no fate with predictable goals or rewards controlling the outcomes here, only the hand of the author, with her long view and broad themes.

The above quotation is not really a spoiler, since this unusual novel features a cast of characters whose lives change constantly in response to the circumstances of their lives. Even death is not permanent. If the unnamed main character makes a bad choice and dies, usually through no fault of her own, German author Jenny Erpenbeck simply changes one or more of the conditions which brought about the character’s death and its terrible consequences to the family and retells her story. In fact, the unnamed main character here has five “deaths” in the novel’s five “books,” and other characters experience similar changes of fortune as the author examines the very nature of time, mortality, fate, coincidence, and the effects of a death or other terrible event on the people connected to that character. There is no heavenly hand, no higher deity, no fate with predictable goals or rewards controlling the outcomes here, only the hand of the author, with her long view and broad themes.

Erpenbeck aims high, creating an unnamed main character from early twentieth-century Galicia (now incorporated as parts of Poland and Ukraine) who endures two world wars and their aftereffects, the growth of communism, the division of Germany and later the fall of the Berlin Wall, and other major events of European history over the course of a century. The main character’s death-defying personal traumas match those wrought by political changes, and as she endures, or dies and is given a second chance, she also becomes an “Everywoman” for the century. The main character’s intimate life story, portrayed within the context of major historical events in various locations in Eastern Europe, makes the small details of a person’s life feel real at the same time that major political and sociological ideas are sweeping the continent. Her setting becomes the world of Europe in miniature, a microcosm of the continent over the course of a century.

The country which was Galicia in 1914 has now been incorporated into Poland and the Ukraine. Its former territory is now bordered by the present countries of ( E – W) Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Moldava.

The novel opens with the death of an eight-month-old baby shortly after the beginning of the twentieth century and vividly recreates the personal devastation it brings to the child’s mother and the family surrounding her. The baby’s Jewish grandmother, whose husband had been killed by a neighbor during a bloody pogrom by Poles against Galician Jews, had arranged for the baby’s mother, who survived, to marry a “goy,” enhancing her chances to live, she believed, but this daughter’s half-Jewish baby has just died anyway of unexplained causes. As the mother must reorder her life following the baby’s death, her “goy” husband learns that if they had put snow on the baby’s chest, under its shirt, that it might have stimulated its breathing impulse and kept the baby alive. Then “fate would have kept quiet, and this first moment when the child might have died would have passed without further ado,” and without changing the lives of everyone in the family.

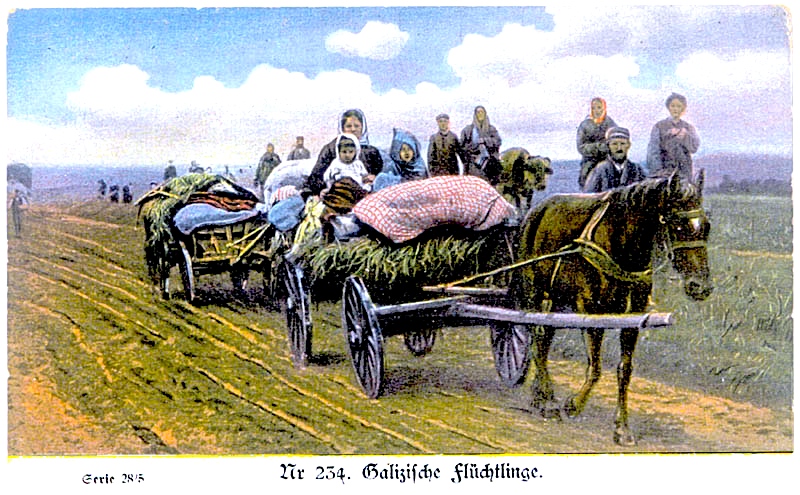

Book II takes place in 1919, after World War I, and what is left of the family has moved to Vienna, where 450,000 refugees like them from Galicia and 150,000 refugees from other places in Europe have congregated, hoping to find food. Instead they find themselves taking turns standing in lines all night in order to get a small piece of cow’s udder for “food.” The main character, who is the subject of the opening quotation of this review, “dies” here at the hands of a medical student who sees her and thinks that she is a whore who has rejected him. The girl, shot, might have been a writer, and she has hidden some writing behind the wardrobe.

The medal of the Great Patriotic Order of Merit, given to Soviets who were especially deserving, was won by one of the characters here.

The first two “books” of the novel, tension-filled and dramatic, keep the focus on the relationships among time and chance and death, while each “Intermezzo” between the chapters offers suggestions regarding an alternative time frame which could have changed the course of lives. The smooth descriptive prose, trenchant dialogue (both real and imagined), and the occasional glimpses of hope as the author changes the outcomes of a death provide ample opportunity for the reader to reflect on the themes and enjoy the author’s creativity in conveying them without bogging down the narrative with an excess of philosophizing. Book III takes a new direction, and the narrative style changes as description becomes subordinated to the tumult of political events. Here, it is 1935, and the main character, a committed communist, has gone to Moscow, become involved in political intrigue, and walked the narrow path between the Trotskyites and the Stalinists. Married, she watches as her husband goes off to war and later gets arrested. She herself is suspect regarding her ideas. The horrors of Russian life and the threats of the gulag are front and center, with images which feel almost rat-a-tat-tat in the precise staccato of their presentation. The main character is writing an apology for her life in an effort to save it and that of her husband, something which most readers who have studied this period will find familiar, and even the sections which look like poetry feel abrupt, constrictive. The emphasis on the political and sociological, while important from the point of view of twentieth century history, supersedes that of the main character here, and some readers may find their attention to the narrative wandering in this section.

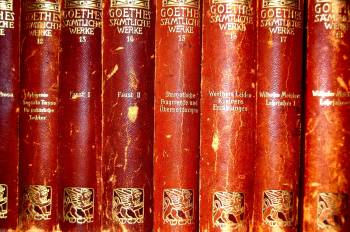

Throughout the novel, a collection of the works of Goethe becomes symbolic for the power of writing and its importance. This photo shows Vols. 12 - 18, including both volumes of Faust.

Book IV continues the story through the next generation represented by the son of the main character, who has many questions about his past. Book V, one which will hit hard for anyone over sixty, depicts the life and thoughts of an elderly woman, Frau Hoffmann, age ninety and in a home for the aged, as she and her heirs separately relive her experiences through the possessions which she has left behind. Erpenbeck deserves high praise for writing a novel about major ideas in a serious and literary way, never underestimating the reader and always providing new insights which expand our view of the past and increase our understanding of themes. With the exception of Book III, which seems to lose its way, this is a first-class literary novel which deserves all its attention and praise.

Photos, in order: The authors’s photo, by Maarten ten Haaff, appears on http://nrcboeken.vorige.nrc.nl/

The map of Galicia in 1914, shows a country which has now been incorporated into Poland and the Ukraine. Its former territory is now bordered by the present countries of ( E – W) Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Moldava. http://mobile.ztopics.com/

This 1918 photo of Galican refugees to Austria, and a story about them, appears on http://www.austrianphilately.com/

The Great Patriotic Order of Merit, won by one of the characters here, is shown on http://daliscar.deviantart.com

The 40-volume Collected Works of Goethe, a recurring motif here, represents the power of writing and its importance. This photo shows Vols. 12 – 18, and the includes two volumes of Faust. http://goaliesanxiety.blogspot.com/

ARC: Other Press