Note: Swiss author Peter Stamm was WINNER of the Friederick Holderlin Prize in 2014 and was SHORTLISTED for the Man Booker International Prize in 2013.

“She couldn’t remember how the crash had come about….[but] suddenly she understood that time had a direction, that it was irreversible. Her first memory was that sense of not being able to do anything anymore, of having no force and no mass. It was as though consciousness had already deserted her body, which accelerated…collided…was thrown back…hit something else in a ridiculous to-and-fro.”

Gillian, a TV commentator and drama school graduate, has just begun to regain consciousness in the hospital following an accident which has killed her husband Matthias, and as her memory of blue water and empty space comes and goes, she alternates between awareness of her surroundings and complete befuddlement. The impact of the crash has destroyed her face, and it will be many surgeries and many months before it can be rebuilt. She “had always known she was in danger, that she would sometime have to pay for everything. Now she had paid.” She and her husband, both intoxicated, had been quarreling because he had found a long-forgotten roll of film hidden in her desk, had had it developed, and was not pleased by what he saw. Already jealous about her career, her friendships, and her easy conversations with those she interviews, Matthias was outraged – “no one took him seriously” – later refusing to let her drive, though he was even more intoxicated than she. Now he is dead, and she will not have a real face for six months, at least.

Gillian, a TV commentator and drama school graduate, has just begun to regain consciousness in the hospital following an accident which has killed her husband Matthias, and as her memory of blue water and empty space comes and goes, she alternates between awareness of her surroundings and complete befuddlement. The impact of the crash has destroyed her face, and it will be many surgeries and many months before it can be rebuilt. She “had always known she was in danger, that she would sometime have to pay for everything. Now she had paid.” She and her husband, both intoxicated, had been quarreling because he had found a long-forgotten roll of film hidden in her desk, had had it developed, and was not pleased by what he saw. Already jealous about her career, her friendships, and her easy conversations with those she interviews, Matthias was outraged – “no one took him seriously” – later refusing to let her drive, though he was even more intoxicated than she. Now he is dead, and she will not have a real face for six months, at least.

What follows in this novel of relationships by Swiss author/dramatist Peter Stamm is a vibrant story of love with its many complications, as damaged people, including Gillian, try to rebuild their lives and find some sort of peace. Time is fluid here, as memories intrude for Gillian, and as Stamm, dramatist that he is, recreates much of her life in vivid scenes of natural and revealing dialogue. As in Stamm’s Seven Years, a previous novel reviewed here, marriage among these characters feels more like a merger than an overwhelming sense of commitment to the well-being of another person, and few of these characters express much self-awareness. The result is that the novel speeds along, compelling the reader to keep reading it for its story and its outcome, rather than for any deep self-analysis by the participants or complex thematic development. Though it is tightly and thoughtfully organized, and filled with vibrant imagery, the novel’s main interest is in the ways the characters try to make sense of their lives. What is significantly different from Stamm’s earlier novel Seven Years is that this one is full of dark ironies and is often funny as the author sees and highlights the absurdities in the lives of these shallow people.

While Gillian is in the hospital, an exhibition poster, similar to this one by John Armleder, is on the wall opposite her bed.

The novel divides into three sections: The first is focused on Gillian, whose “life before the accident had been one long performance – her job, the studio, the designer clothes, the trips to cities, the meals in good restaurants, the visits to her parents and to Matthias’s mother. It must have been a lie if it was so easy to destroy with a moment’s inattention.” The person who took the photographs of Gillian is artist Hubert Amrhein, age thirty-nine, who usually photographed ordinary women performing ordinary tasks. Gillian had found him to be a “jerk” and a “chatterbox,” but also found his instinctive connection to what she herself was thinking during an interview to be “striking.” Still, Hubert’s reaction toward her in the photographs was almost indifferent. “I get the feeling that there’s nothing coming from you,” he says, as he looks at her images.

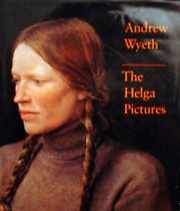

The unnamed American artist mentioned by Hubert’s gallerist as having secretly painted the same neighbor woman for fifteen years, may have been Andrew Wyeth.

The second section, from Hubert’s point of view, takes place five or six years later, when he is married to Astrid, though they are emotionally separated. Anxious for even more “space,” Astrid now wants him to remove all his memorabilia and the old work which he has been storing in their attic. When he is invited to have an exhibition at a cultural center in the mountains one summer, he accepts, though he has not done any new work in years. Later he learns from his “gallerist” about a famous American painter who painted pictures of a neighbor for fifteen years, keeping the paintings hidden away for that whole time, and he wonders if he has anything hidden away in his own attic that he can use or adapt for the exhibition. He does not know that one of his former models, Gillian, now known as Jill, is the person directing this event.

At one point Hubert recalls the landscapes of Georgia O’Keeffe, where the hills looked like the bodies of naked women.

The third section consists of what happens in the present when Hubert goes to the cultural center and reconnects with Jill. Much from the past is revealed here, as he tries to reinvigorate his sense of creativity; as his wife tries to get him out of her life; and as he begins to respond to the peacefulness of the mountains. In what amounts to a coda to all this, Gillian/Jill comes to her own awakening and begins to think about changes in her own life. Stamm’s sense of direction for the action is unerring, and his ability to focus is total. His characters, though limited in personal awareness, are consistent, and their inner thoughts are clearly revealed to the reader. Because of this realism, most readers will be hoping for the characters to awaken, eventually, to new possibilities in their personal lives, and it is this hope which keeps the reader engaged, rather than the development of complex themes.

When Jill shows Hubert the photos he took of her, he is struck by one which shows her vulnerability. She is sitting with her hands in a pose which Hubert has “cribbed from Edvard Munch” in a portrait he did of a young girl.

The author’s own interest in art infuses this novel, as it did in Seven Years, and he sets up parallels between some of his characters and famous artists whose lives have similarities to the characters’ lives – Andrew Wyeth, Georgia O’Keeffe, and even Edvard Munch. The famous artists have managed to live with their creativity and to use it, however, and one is not sure whether Stamm’s characters, especially Hubert, in search of inspiration, will also be able to gain the insights to do so, too. After the exhibition has come and gone, Hubert makes some decisions, and soon after that, Gillian/Jill remembers the origins of her “blue water” imagery, which opens the novel. It remains to be seen if she will act on what she discovers.

[Michael Hofmann, one of the premier translators of German language novels, has translated this and several of Stamm’s other books.]

ALSO by Peter Stamm: SEVEN YEARS, AGNES, TO THE BACK OF BEYOND

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.roxy.ulm.de/

The abstract picture by Geneva artist John Armleder, similar to one on the wall of Gillian’s hospital room, is one of a pair done in 2003: http://www.nonobjectifsud.org/2007/aja1.html

John Wilmerding’s book about Andrew Wyeth’s “Helga Pictures,” was released in 1987 and may be found on Amazon and other book-selling sites. http://en.wikipedia.org/

Georgia O’Keeffe’s “Red Hills, Gray Sky,” from the late 1930s, is shown on http://dailycristo.com

Edvard Munch’s depiction of the vulnerability of a young girl (1894) stands in sharp contrast to his most famous painting, ” The Scream.” Ironies abound when thinking of this sweet painting in relation to Gillian, though she posed for her photo by Hubert in the same position. http://www.edvard-munch.com

ARC: Other Press