Note: This novel has been Shortlisted for the 2013 Booker Prize.

“[On harvest days] our work is consecrated by the sun. Compared to winter days…it’s satisfying work, made all the more so by the company we keep, for on such days all the faces we know and love…are gathered in one space and bounded by common ditches and collective hopes…Anything we say is heard by everyone. So there is openness and jollity.”

Jim Crace’s powerful and dramatic new novel, set in an unnamed rural farm community in England in an unstated year, wastes no time in shifting the atmosphere from the “jollity” and feeling of community resulting from the hard work of the harvest to the kind of mindless hysteria, based on fear, which American readers will instantly recognize as similar to that which existed during the Salem witch trials (as is seen in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible). Working for Master Kent, whose wife inherited a large portion of land from her family, the farmers on the land are all too aware that theirs is a tenuous life, one in which they have a small cottage for their families and a small portion of the harvest for their own use in exchange for back-breaking work under uncertain weather conditions, with most of the harvest going to Master Kent. Bad weather or a bad harvest means hungry winters and less seed for the next season’s planting.

Jim Crace’s powerful and dramatic new novel, set in an unnamed rural farm community in England in an unstated year, wastes no time in shifting the atmosphere from the “jollity” and feeling of community resulting from the hard work of the harvest to the kind of mindless hysteria, based on fear, which American readers will instantly recognize as similar to that which existed during the Salem witch trials (as is seen in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible). Working for Master Kent, whose wife inherited a large portion of land from her family, the farmers on the land are all too aware that theirs is a tenuous life, one in which they have a small cottage for their families and a small portion of the harvest for their own use in exchange for back-breaking work under uncertain weather conditions, with most of the harvest going to Master Kent. Bad weather or a bad harvest means hungry winters and less seed for the next season’s planting.

Main character Walter Thirsk came to the manse originally as Master Kent’s manservant, but he, too responds to the need for extra hands when harvest day arrives. He has married one of the women from a farming family, and though now widowed, he still lives in a cottage among these workers and feels closer to them than to the residents of the Master’s manse. Times have changed since he first arrived, however, and the number of workers on the farm has decreased below the number needed to bring in a big harvest. “We’ve lost good friends but not had much success with breeding their inheritors or raising sturdy offspring. We’re growing old and faltering. Harvests have been niggardly…[and] there are days in winter when our cattle dine and we do not.” This year is especially difficult. A stranger has been watching the men harvest the barley crop, recording what is happening, measuring and surveying, and appearing to map the land. No one knows what he is doing there, but tensions rise as some workers begin to wonder if the Master is going to sell the land on which they are totally dependent.

On the last day of the harvest, two plumes of smoke are seen—one from a hearth fire outside a remote hut newly built by three strangers. An ancient ruling allows the right of settlement and a portion of the harvest for any “vagrants who might succeed in putting up four vulgar walls and sending up some smoke before we catch them doing it.” Three people, two men and a woman who resembles a sorceress have staked out a claim on the Master’s land and, with it, a right to a portion of the meager harvest the community of workers has just worked so hard to bring in. When the newcomers’ hut is investigated, the farmers discover bird bones, proof enough for some workers that they have stolen and eaten some of the Master’s prized doves. The newcomers, overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of hostile residents, greet them armed with bows and arrows, further heightening the tension.

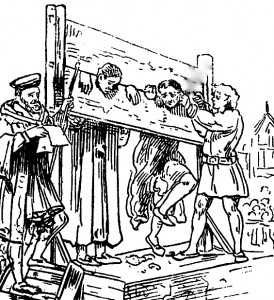

The second plume of smoke proves to be the roof of the Master’s haylofts, where his doves live. Though Walter Thirsk knows from the outset that the newcomers have not set the barn fire, he keeps his mouth shut when the group of harvesters decides differently. Thirsk saw three residents among the harvesters who were under the influence of the wild fairy cap mushrooms they collected that day and heard them implying their involvement, but he convinces himself that they have simply set the fire in an effort to smoke out the doves. As there is no constable nearby, the Master eventually sentences the two newcomer men to the pillory – seven days and nights to be spent confined outside, uncovered, in the elements – not for the burning of the barn but for the theft of one or more of the Master’s doves. Thirsk knows that this charge, too, is false. The feathers found at the hut were black, not white, but still, he refuses to act against his loyalty to the harvesters.

The shorter of the newcomers was unable to put his feet flat on the ground when he was pilloried, forcing him to stand on tiptoe for the entire time of his punishment.

Creating a lively and exciting narrative from this fraught beginning, Jim Crace quickly advances the novel from its initial feeling of foreboding to a feeling of terrible inevitability, adding details and events which horrify the reader for what they portend. Crace’s community is pagan – nature-bound, not traditionally religious – and this shift in emphasis forces the reader to take a harder look at the motivations of the characters and see the action for the human moral tragedy it is, one that exists apart from any religious fervor which might take place in other communities. One cannot blame religiosity or ignore the biggest conflicts – those between the haves and the have-nots – whether they are between the master and the workers, between the long-time farm workers and the newcomers, or between those with a sense of social responsibility and those protecting their own self-interest.

Guilt vs. innocence, the use of raw power to control outcomes, the callous manipulation of resources (such as land) at the expense of human beings who are dependent upon it for their very survival, the question of one’s responsibility to a small community as opposed to one’s responsibility to uphold the truth, the question of vengeance, and ultimately, the question of how it is possible to define “right” in a community which has no religion and no legal system are all important themes represented in this largely allegorical novel. Vibrant descriptions of the changing seasons and of the characters’ connections to nature add a sense of universality and gravitas to the action, and the well-developed and sensitive characterization of Walter Thirsk make him a character with whom most readers will identify, despite his weaknesses. Written in a language and style that feels reminiscent of the period, this is a novel to sink into, one in which the author is so in control of his material, style, and themes that the reader can sit back and savor the narrative, its twists, turns, and inevitabilities, while also believing that the author holds out hope for the future of mankind.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.bbc.co.uk/

The barley field appears on http://peacedeen.wordpress.com

The orange fairy caps, photo by Bob Hoefer, may be found on http://www.bikerumor.com

The drawing of the pillory is from http://www.reocities.com/