“Hindsight is a wonderful thing, but I look back now and I think of…[the Toxleys] standing there on the platform at Thorpe Station [when I arrived] and I want to scream at them, I want to run and shake them, I want to look them squarely in their faces and say, you knew, you knew even then. Why didn’t you warn me?”—Eliza Caine

The Halloweens of my childhood were times in which our imaginations ran riot with mysterious haunted houses, the terrifying old “witches” who inhabited them, and the ghosts and other presences who kept them company. The scariest film I’d ever seen was “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” with its Headless Horseman, nothing like the films of today. Memories of old stories like these come roaring back to life with this Dickensian melodrama, set outside of Norfolk, England, in 1867. Eliza Caine, who has suffered a series of personal disasters which have left her an orphan, has made a sudden decision to leave the family “home” in London, in which she has spent her life, to accept the position of governess for a family she does not know in a city she has never seen. She is anxious for change, however. Just one week past, her father had ignored her pleas that he remain at home to nurse his cold and had, instead, attended a reading by Charles Dickens on a miserable, rainy night. He succumbed to fever shortly afterward. Almost immediately after her father’s death, Eliza is informed that the family home is not, in fact, owned by the family, and that she will have to vacate the house. Seeing an advertisement in the newspaper for a governess, signed by “H. Bennet,” she has chosen to leave her current teaching job at a girls’ school and move elsewhere.

The Halloweens of my childhood were times in which our imaginations ran riot with mysterious haunted houses, the terrifying old “witches” who inhabited them, and the ghosts and other presences who kept them company. The scariest film I’d ever seen was “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” with its Headless Horseman, nothing like the films of today. Memories of old stories like these come roaring back to life with this Dickensian melodrama, set outside of Norfolk, England, in 1867. Eliza Caine, who has suffered a series of personal disasters which have left her an orphan, has made a sudden decision to leave the family “home” in London, in which she has spent her life, to accept the position of governess for a family she does not know in a city she has never seen. She is anxious for change, however. Just one week past, her father had ignored her pleas that he remain at home to nurse his cold and had, instead, attended a reading by Charles Dickens on a miserable, rainy night. He succumbed to fever shortly afterward. Almost immediately after her father’s death, Eliza is informed that the family home is not, in fact, owned by the family, and that she will have to vacate the house. Seeing an advertisement in the newspaper for a governess, signed by “H. Bennet,” she has chosen to leave her current teaching job at a girls’ school and move elsewhere.

From the beginning of the novel, Irish author John Boyne draws parallels between Dickens’s work and his own. The Dickens reading, which Eliza and her father attend, is of a ghost story Dickens wrote for the Christmas number of All the Year Round, “a most terrifying tale…of the paranormal, of the undead, of those pitiful creatures who wander the afterlife in search of eternal reconciliation…I wrote it,” Dickens confesses, “to chill the blood of my readers and dispatch ghouls into the beating heart of their dreams.” Eliza is particularly vulnerable to suggestion, at this point, because she has recently seen another face just below her own in her mirror, a face resembling that of her deceased mother and which she sees again as she walks to hear Dickens. After the reading, she admits to her father that “I don’t think I’ve ever experienced fear in the way that others do. I don’t understand what it is to be truly frightened,” though she acknowledges that stories of the afterlife and about forces that the human mind cannot understand are “disquieting.” She prefers Oliver Twist and David Copperfield to Scrooge and Marley.

St. James Church, Paddington, where the funeral was held for Eliza’s father. Photo by Martin Addison

Eliza is about to discover just how “disquieting” her life can be, as author Boyne creates a story about the inhabitants of Gaudlin Hall, the estate to which Eliza is traveling, which directly parallels much of what Charles Dickens has included in the story he has read to his audience. Many clichés of spooky Victorian novels are repeated here: Eliza arrives by train during a fog so dense she can not even see in front of her (and almost gets hit by a passing train). She collides with “HB” on the platform, and only later realizes that it is the “H.Bennet” who advertised for the governess position that she has accepted. HB is now racing to catch the train back to London. Heckling, the farm worker who picks her up and drives her to Gaudlin Hall, reluctantly answers her questions about H. Bennet and the “Master” of Gaudlin by saying only that Bennet was not the owner of Gaudlin but a departing employee, a revelation which shocks Eliza, who had been imagining herself as “the young lady at the heart of Pride and Prejudice,” Dickens’s novel of the Bennet family. As for the Master of Gaudlin, “There ain’t no master of Gaudlin. Not no more. Missus took care of that, di’nt she?”

Two children, Isabella Westerley, a twelve-year-old with a “mistress-of-the-house expression on her face,” and Eustace, her innocent eight-year-old brother, are the children Eliza will teach. Except for Heckling, a Mrs. Livermore who comes every day, presumably with food, and who then seems to vanish, and Mr. Raisin, the Westerley family lawyer (and whose secretary is named Mr. Cratchett), Eliza is the only other adult at Gaudlin Hall. She soon discovers that there, are, however, “presences” at Gaudlin which pull on her ankles when she is in bed, try to strangle her while she is sleeping, prevent doors from opening, push her out windows and pull her back, change cold water to boiling water without warning, and stir up tornado-like winds which buffet only her. It is not long before she concludes that there are two distinct presences at work, vying for control of her life, as they also did with the five governesses who preceded her over the course of the past year.

In the midst of her turmoil, Eliza seeks out Rev. Deacons of the local church for a theological discussion of issues that were undoubtedly being discussed in England in 1867, the time of this novel. Though Boyne does not spend much time on theology, this was a time of great upheaval, just eight years after Charles Darwin published The Origin of the Species, which cast doubt on the church’s Doctrine of Separate Creation, and it was only one generation before the movement toward Spiritualism of which Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a strong proponent, with public séances and attempts to raise ghosts through mediums. Heaven, Hell, and even Purgatory are not enough, Eliza Caine feels, to explain the presences she has experienced in Gaudlin Hall, and she suggests that there may be a fourth level of existence in which a spirit can linger for a time on earth, watching over those it loves, until it is “reconciled” with the forces of nature, and the ties that have bound it to earth are then cut.

Boyne’s goal here is pure entertainment, however, and he matches his prose style to that of Dickens effectively, though in one case, after a question, one finds the forced archaism, “Answer came there none.” All the clichés of Victorian plot appear here, and the dramatic and inexplicable actions by ghosts create an atmosphere of doom which will keep a smile on the face of readers familiar with the novels of the period. The characters are vehicles for the plot, rather than compelling personalities in their own right, and the lack of realism throughout is exactly what one expects of a Victorian ghost story. Only a dark twist in the conclusion takes this novel into more modern times, stylistically.

ALSO by John Boyne: THE ABSOLUTIST, A LADDER TO THE SKY

Eliza mentions several times that she has used a “dandy-horse,” a kind of scooter with a seat, when she has gone on short trips.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Mark Condren appears here: http://www.theguardian.com/

The funeral of Eliza’s father takes place at St. James Church, Paddington. Photo by Martin Addison on

http://commons.wikimedia.org

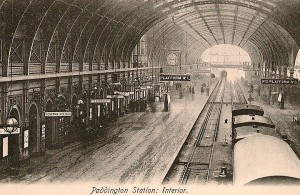

Paddington Station, from which Eliza took the train to Norfolk looked like this in Victorian times:

http://en.wikipedia.org

The gargoyles at Gaudlin fall occasionally. Those pictured are from Magdalen College:

http://www.thelandofshadow.com

The “dandy-horse,” similar to a scooter with a seat, was invented by Karl Von Drais in 1819, and is depicted on http://en.wikipedia.org/

ARC: Other Press