“Was it possible that he, striding freely down the street of an American city, the city of his birth and schooling and the cradle of his hopes and dreams, had waved it all aside beyond recall? Was it possible that he…and all the other American-born, American-educated Japanese who had renounced their American-ness in a frightening moment of madness had done so irretrievably? Was there no hope of redemption?” – Ichiro Yamada, in Seattle.

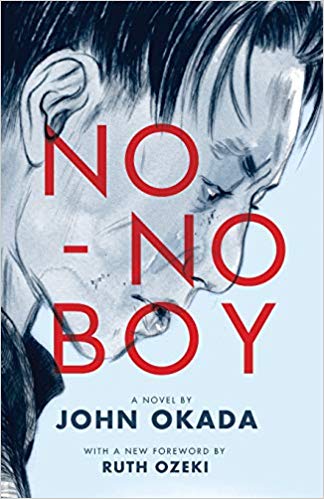

In this unique, ground-breaking novel, John Okada creates such a vibrant picture of the first- and second-generation Japanese-Americans during and immediately after World War II, that it is impossible to imagine readers of this book not being universally moved by what they read here. The Foreword alone, written by Ruth Ozecki as a letter to the author in April, 2014, when this edition was published, attests to the fact that Okada, who died in his forties in 1971, never knew how important No-No Boy would become – the only such book ever written by a Japanese-American about the plight of Japanese immigrants who came under immediate and universal suspicion the instant Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Over 110,000 people who had come to the US from Japan, some of them many years ago, were rounded up and sent to prison camps in the desert for the duration of World War II, forced to give up their homes, their jobs, their businesses, and their dreams. Young Japanese-American men, however, were offered a chance to prove how American they had become. A required questionnaire contained two questions regarding their loyalty: Were they willing to serve in combat duty in the US armed forces, and would they swear “unqualified allegiance” to the country and defend it from any attack by foreign or domestic forces.

In this unique, ground-breaking novel, John Okada creates such a vibrant picture of the first- and second-generation Japanese-Americans during and immediately after World War II, that it is impossible to imagine readers of this book not being universally moved by what they read here. The Foreword alone, written by Ruth Ozecki as a letter to the author in April, 2014, when this edition was published, attests to the fact that Okada, who died in his forties in 1971, never knew how important No-No Boy would become – the only such book ever written by a Japanese-American about the plight of Japanese immigrants who came under immediate and universal suspicion the instant Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Over 110,000 people who had come to the US from Japan, some of them many years ago, were rounded up and sent to prison camps in the desert for the duration of World War II, forced to give up their homes, their jobs, their businesses, and their dreams. Young Japanese-American men, however, were offered a chance to prove how American they had become. A required questionnaire contained two questions regarding their loyalty: Were they willing to serve in combat duty in the US armed forces, and would they swear “unqualified allegiance” to the country and defend it from any attack by foreign or domestic forces.

As Ruth Ozeki points out in the Foreword, some young men immediately signed “yes” and were drafted into the army. Many, however, still had family in Japan and were worried about killing a family member there. Others found the English wording of the questions unclear, and still others were resentful that the US had branded them “enemy aliens” and stripped them of all rights of citizenship, even though some had been born in the US over twenty years ago. Anyone who answered “no-no,” in answer to the two loyalty questions, was “found guilty of draft evasion, arrested, and taken first to jail and then to a maximum security segregated detention facility for the final years of the war.” For these “no-no boys,” the aftermath of the war was just as terrible as their imprisonment. They were universally regarded as traitors to the country and to their families in the US. Author John Okada himself answered “yes, yes.” He served in the Army Air Forces as an interpreter, flew reconnaissance missions over Japanese-held territory, and returned to Japan as a member of the US occupying forces at the end of the war. He was so saddened by the plight of the no-no boys after the war, however, that he uses no-no boy Ichiro Yamada as the main character of this extraordinary – and unique – novel of character, one which I found so moving and so compelling that it is now at the top of my All-Time Favorites List.

The Wonder Bread factory in Seattle was many blocks from the Yamadas’ store, but Mrs. Yamada always walked the distance.

Originally published in English in Japan in 1957, and again in the US in 1976, five years after the author’s death, the book was published for the third time in 2014, and this time, John Okada may finally get the recognition he has not received to date. His main character, Ichiro Yamada, born in the US, is both a symbol of the no-no boys and a character so vividly drawn that readers, regardless of their own backgrounds, will identify with him and his post-war problems. Returning to Seattle, his family “home,” after four years, two in camp and two in prison, he is immediately greeted on the street by an old friend who wants to have a drink – until he discovers that Ichiro is a no-no boy, at which point he hurls profanities and spits. Arriving at “home” to the family’s new address in the old neighborhood, his father speaks Japanese to him and “fondly, delicately, [places] a pudgy hand on Ichiro’s elbow and looks up at his son” – no hugs, no tears, no overt signs of happiness that Ichiro is finally home. His mother is out getting Wonder Bread from the bakery to sell at the grocery store that they now run. When she returns and is told that Ichiro is back, she ignores him, her comment being “The bread must be put out.”

Kenji’s friend Emi lives in the countryside, where life includes music from a Zenith console and a piano.

Suddenly coming to stunning realizations of the differences between his mother, her culture, and himself, Ichiro now comprehends for the first time that it was his mother’s single-mindedness and her overwhelming example which made him deny the American half of himself by refusing to serve in the army. His mother insists that the Japanese have won the war and that boats will be coming soon to take them all back to Japan, and she is waiting impatiently for “the day of glory” which she believes is “close at hand.” Ichiro, now feeling totally alone in the country where he has lived all his life, tries to reconnect with old friends, one of whom spends his time eating, drinking, and trying to be merry, a discovery which increases Ichiro’s despair. A visit with his favorite college professor feels like “meeting someone you knew in a revolving door, meeting without hearing, smiling without feeling.” Another “friend” publicly identifies Ichiro as a no-no boy and mocks him. It is not until he meets with Kenji, an amputee from the war who is slowly losing more of his leg to infection, that he reconnects with someone whose attitudes and problems after the war seem to parallel his own. It is this warm and caring friendship which forms the crux of the novel, thematically. In time, Kenji introduces Ichiro to Emi, a young married woman living in the countryside with a good heart and her own story.

Eventually, Kenji’s wound becomes worse, and Ichiro drives him to the VA Hospital in Portland, Oregon, for more surgery, leading to several turning points and recognitions. A stop at a local cafe and conversation with a too-friendly Japanese waiter send Ichiro to rock bottom, though once again, Kenji bolsters his spirits, this time from a hospital bed. Several more life-changing experiences draw the reader even more firmly into the lives of these characters as the novel continues, and becomes increasingly powerful. As the author continues to develop his themes of identity and heritage, he emphasizes even more fully how the US policy of isolating Japanese residents in camps and requiring young men to serve in the army damaged many lives. Author John Okada served his time in this army, but it is with this book that he leaves a lasting legacy which allows every reader to feel and share his feelings and unique insights in a book which I will be recommending to everyone I know for a long, long time.

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://www.facebook.com/JohnOkadaBook/

The Wonder Bread factory in Seattle was many blocks from the Yamadas’ store, but Mrs. Yamada always walked the distance. https://blog.seattlepi.com/ By Grant M. Haller.

Kenji’s friend Emi lives in the countryside, where life involves music from a Zenith console and a piano. https://www.pinterest.com Uploaded by Jeff Webster.

A conversation by an overly friendly waiter at a cafe in Portland sends Ichiro spiraling downward. https://www.coolcousin.com

Downhill in the fog of Seattle: https://www.seattlepi.com/