“Only in exceptional cases do people reside in condemned buildings. So one could say it was noteworthy that a single condemned building in Gnesta [Sweden], now housed the following: one American potter, two very similar and dissimilar brothers, one angry young woman, one escaped South African refugee, and three Chinese girls with poor judgment. All of these people found themselves [living] in nuclear-weapons-free Sweden. Right next door to a three-megaton atomic bomb.”

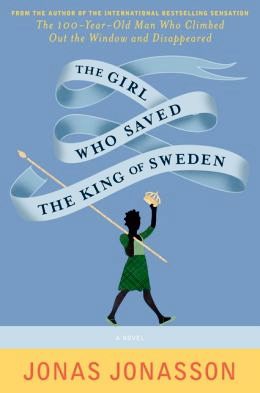

So wild and imaginative that it challenges the very meaning of the word “farce,” which, for me is usually something light-weight, silly, and easily forgotten, Swedish author Jonas Jonasson expands this “farce” beyond the customary local or domestic focus and uses the whole world as his stage. Drawing his characters from South Africa, Israel, China, and Sweden, with a couple of Americans also earning passing swipes, he focuses on cultural and racial issues; world affairs, including the modern political history of several countries; and the accidents of history which have the power to change the world. The craziness starts with the novel’s over-the-top opening line: “In some ways they were lucky, the latrine emptiers in South Africa’s largest shantytown. After all, they had both a job and a roof over their heads.” And for the next four hundred pages, the bold absurdity continues, spreading outward until it eventually absorbs the kings, presidents, and prime ministers of Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

So wild and imaginative that it challenges the very meaning of the word “farce,” which, for me is usually something light-weight, silly, and easily forgotten, Swedish author Jonas Jonasson expands this “farce” beyond the customary local or domestic focus and uses the whole world as his stage. Drawing his characters from South Africa, Israel, China, and Sweden, with a couple of Americans also earning passing swipes, he focuses on cultural and racial issues; world affairs, including the modern political history of several countries; and the accidents of history which have the power to change the world. The craziness starts with the novel’s over-the-top opening line: “In some ways they were lucky, the latrine emptiers in South Africa’s largest shantytown. After all, they had both a job and a roof over their heads.” And for the next four hundred pages, the bold absurdity continues, spreading outward until it eventually absorbs the kings, presidents, and prime ministers of Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

Author photo by Sara Arnald

Main character Nombeko Mayeki, a thirteen-year-old orphan in the late 1960s, has been a latrine worker in Soweto, South Africa’s largest shantytown, for the past eight years, educating herself on the job by counting the barrels she carries, then gradually making the counting exercises harder until she can multiply ninety-five by ninety-two in her head. She is as verbal as she is mathematical – and so astute as to motivations of those around her that she progresses quickly, both on the job and in her personal development, eventually learning to read and write and proving to be far more clever than the people who teach her. By the time she turns fifteen, she has been so successful that she has accumulated a large store of raw diamonds and escaped Soweto on foot hoping to reach Pretoria, fifty miles away. Before she gets there, however, she is hit by a drunk driver who claims she was “walking on a sidewalk meant for whites.” A judge sentences her to work for the man who struck her, at half-salary for seven years because of the damage she caused to the car. The drunk driver, it turns out, works at Pelindaba, a nuclear research facility north of Johannesburg.

Confined for security reasons behind two fences for nine years, not the required seven, she meets several Chinese girls who teach her Chinese while passing along atomic secrets to the Chinese government. Nombeko later meets representatives of Israel’s Mossad and is on hand when the facility discovers that they have ordered six bombs to be made, though seven have been delivered. The fate of the seventh bomb in the early 1980s controls the plot for the rest of the novel.

Alternating with the story of Nombeko is the story of Ingmar Qvist, a man whose life’s mission is to shake the hand of Swedish King Gustav V, who, in 1928 celebrated his seventieth birthday by giving out stamps with his photograph to the public. Ingmar, only fourteen at the time, is horrified that he forgot to thank the king and has dreamed ever since of meeting him so he can look him in the eye to express his gratitude.

Spending much of his money on schemes to meet the king, Ingmar discovers, upon finally meeting him, that the king continuously looks beyond him, an event which not only insults him but causes him to assault the king, and to be struck by the king with his cane. Instantly, he becomes virulently anti-monarchy, dedicated to deposing the king and his heirs. Ingmar’s twin sons, both named Holger, disagree about the future. One continues to be strongly in favor of the monarchy, the other wants it abolished in favor of democracy.

Within this framework, the author creates a vibrant farce involving the loyalties and relationships among people, countries, and political points of view from the time of Sweden’s King Gustav in the 1940s up through the nuclear developments in South Africa in the 1970s and 1980s, the end of apartheid and the Presidency of Nelson Mandela in South Africa in the 1990s, and up to the present in Sweden. With South Africa’s social and political changes in the early 1990s , the government begins to look, long-term, at what might happen if Mandela were to become President and his supporters were to acquire the six atomic bombs which the country has already developed and tested, and the novel becomes more complex. The very real involvement of the Israelis and the Chinese are paramoun t, and when Nombeko eventually arrives in Sweden, accompanied by the seventh bomb, the free-for-all becomes a reality. The two plot lines converge with Nombeko living in a condemned factory building in Gnesta with her bomb and with Ingmar’s sons, Holger One and Holger Two, as the role of the Swedish government in protecting the world against nuclear proliferation becomes critical.

t, and when Nombeko eventually arrives in Sweden, accompanied by the seventh bomb, the free-for-all becomes a reality. The two plot lines converge with Nombeko living in a condemned factory building in Gnesta with her bomb and with Ingmar’s sons, Holger One and Holger Two, as the role of the Swedish government in protecting the world against nuclear proliferation becomes critical.

One of the keys to great farce, it seems to me, is that it says, or implies, much about the truths of our lives within an exaggerated scenario so off-the-wall in its presentation that the reader can laugh, even while recognizing the truths hidden within the craziness. With this novel and its international complications, the genuine recognitions are very dramatic, but, at the same time, the novel sometimes becomes unusually complex, necessitating an exceptionally large number of characters and a length which stretches the limits of the genre.

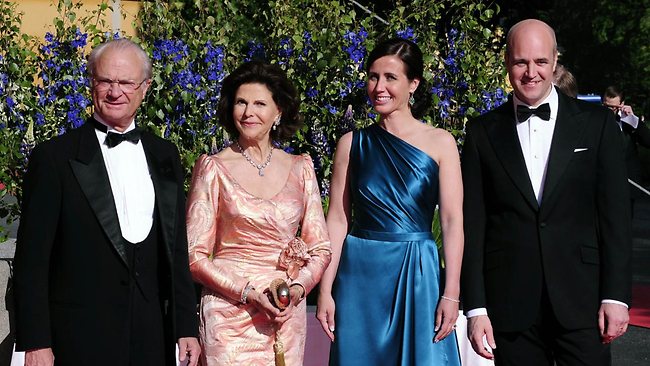

King Carl XVI Gustav (far left) and Prime MInister Frederik Reinfeldt (far right) and their wives at a wedding, a far different situation from being in the back of a filthy potato truck driven by a crazy man.

Jonasson straddles the line admirably, especially since he cleverly matches his plot to real events acted out by real people in Swedish history. The novel ends with a meeting of Hu Jintao, President of the People’s Republic of China, and King Carl XVI Gustav, when Frederik Reinfeldt was Prime Minister. The scenes in which the king and Reinfeldt are confined to the back of a filthy potato truck driven by a crazy man are priceless, representing both real history and the potential horrors which have somehow been avoided – to date. Picaresque, in terms of the plot, which wanders around following the life of Nombeko from the age of thirteen to forty-seven, the novel wastes no time in making its points about personal and political responsibility, or as the author says, “If God does exist, he must have a good sense of humor.”

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Sara Arnold appears on http://olvassbele.com

The shell casings for the “bombs that could never be used” in South Africa, and the story behind them, are shown here: http://newobserveronline.com

King Gustav V (1855 – 1950) and his life are discussed on Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/

A condemned warehouse, similar to the one in which Nombeko and the two Holgers and their friends are living, is seen here: http://www.building-cincinnati.com/

King Carl XVI Gustav and Prime Minister Frederik Reinfeldt, and their wives, dressed for a wedding, are depicted on http://www.news.com.au/ The men look far different here from what they must have looked like when they emerged from the back of a dirty potato truck which also accompanied the seventh atomic bomb.