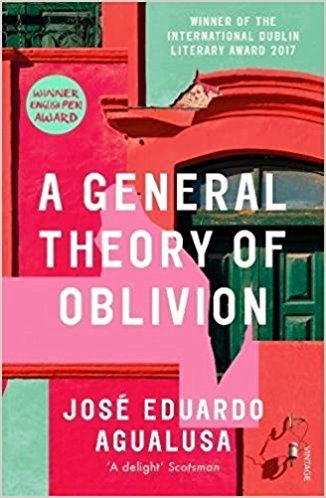

Note: Jose Eduardo Agualusa was WINNER of the International Dublin Literary Award (formerly the IMPAC Dublin Award) for this novel in 2017.

“Ludovica Fernandes Mano died in Luanda…in the early hours of 5 October 2010. She was eighty-five years old. Sabalu Estevao Capitango gave me copies of ten notebooks in which Ludo had been writing her diary, dating from the first years of the twenty-eight during which she had shut herself away. I also had access to the diaries that followed her release, as well as to a huge collection of photographs…and the charcoal pictures on the walls of her apartment. They helped me, I believe, to understand her.”—from the author’s Foreword.

Set in the immediate aftermath of Angolan independence in 1975, after that country’s long-time rule by Portuguese colonists, this novel by Angolan author Jose Eduardo Agualusa reflects the conflicts involved as the country sets up a new government under the Marxists and Leninists who had helped during the revolution, aided by the Soviet Union and Cuba. The war for independence from Portugal is now over, and many who fought in that war are getting ready to fight anew against the one-party Leninist state which has taken its place and now threatens to nationalize all private businesses. Ludovica Fernandes Mano, the fifty-year-old main character and speaker, has been living in Luanda with her sister Odete and brother-in-law Orlando, who works in the diamond trade, and they have begun to fear the future and their roles in Angola. Originally from Portugal, these residents have found that all allegiances and alliances are now in question, and no one knows, for sure, whom they can trust. Threats are being made by unknown players. One morning, without warning, Ludo wakes to find herself suddenly alone in the family’s comfortable apartment. Her sister and brother-in-law have used the cover of night to escape the country, leaving her behind. Ludo, always timid, “never liked having to face the sky. While still only a little girl, she was horrified by open spaces,” and the only really close relationship she seems to have is with her albino German Shepherd dog named Phantom.

Set in the immediate aftermath of Angolan independence in 1975, after that country’s long-time rule by Portuguese colonists, this novel by Angolan author Jose Eduardo Agualusa reflects the conflicts involved as the country sets up a new government under the Marxists and Leninists who had helped during the revolution, aided by the Soviet Union and Cuba. The war for independence from Portugal is now over, and many who fought in that war are getting ready to fight anew against the one-party Leninist state which has taken its place and now threatens to nationalize all private businesses. Ludovica Fernandes Mano, the fifty-year-old main character and speaker, has been living in Luanda with her sister Odete and brother-in-law Orlando, who works in the diamond trade, and they have begun to fear the future and their roles in Angola. Originally from Portugal, these residents have found that all allegiances and alliances are now in question, and no one knows, for sure, whom they can trust. Threats are being made by unknown players. One morning, without warning, Ludo wakes to find herself suddenly alone in the family’s comfortable apartment. Her sister and brother-in-law have used the cover of night to escape the country, leaving her behind. Ludo, always timid, “never liked having to face the sky. While still only a little girl, she was horrified by open spaces,” and the only really close relationship she seems to have is with her albino German Shepherd dog named Phantom.

When someone who claims to be from the Portuguese army comes to the apartment demanding “the stones,” for which, he says, he will release her captive sister, Ludo takes surprisingly forceful action, and she does it alone. Using materials left behind the apartment to build a swimming pool, she bricks up and plasters over the entire entrance to her apartment. Once she has finished, she closes herself in and does not leave for twenty-eight years. Growing vegetables for food, she traps and removes chickens from the balcony of the apartment below her, aiming to catch both a rooster and a hen so that she can have her own flock and their eggs. She catches pigeons, using sparkling diamonds as a lure, and she burns nearly all the furniture for heat. As the years pass, she slowly diminishes the number of books in the library. She spends much time, of course, looking out the window, and she is particularly sad that she is no longer being entertained by a monkey which she has named Che Guevara. When she finally finds him again, she is surprised that he is “watching her with light, wondering eyes. She had never seen such an intensely human look in the eyes of any man,” an irony in keeping with the themes and style of the novel. Eventually, she runs out of notebooks after her years of writing, and she finds herself losing her eyesight. She decides to write on the walls of the apartment in charcoal.

When someone who claims to be from the Portuguese army comes to the apartment demanding “the stones,” for which, he says, he will release her captive sister, Ludo takes surprisingly forceful action, and she does it alone. Using materials left behind the apartment to build a swimming pool, she bricks up and plasters over the entire entrance to her apartment. Once she has finished, she closes herself in and does not leave for twenty-eight years. Growing vegetables for food, she traps and removes chickens from the balcony of the apartment below her, aiming to catch both a rooster and a hen so that she can have her own flock and their eggs. She catches pigeons, using sparkling diamonds as a lure, and she burns nearly all the furniture for heat. As the years pass, she slowly diminishes the number of books in the library. She spends much time, of course, looking out the window, and she is particularly sad that she is no longer being entertained by a monkey which she has named Che Guevara. When she finally finds him again, she is surprised that he is “watching her with light, wondering eyes. She had never seen such an intensely human look in the eyes of any man,” an irony in keeping with the themes and style of the novel. Eventually, she runs out of notebooks after her years of writing, and she finds herself losing her eyesight. She decides to write on the walls of the apartment in charcoal.

Numerous characters make repeated appearances here, and as the long, unfamiliar names, and occasionally nicknames, are often difficult to remember, some readers may want to keep a character list. Part of this need is connected to the ambiguity of time here, which adds to the sense of immediacy and the mood of this novel, though it can be a bit frustrating at times. Dates are rarely included, and narrative episodes are not in chronological order. Che Guevara, the monkey, is mentioned for the first time in an italicized musing by Ludo, but he is not identified as a monkey at that time. Sixteen pages later, he appears again, with no reference to the fact that he has been mentioned before. Jeremias Carrasco is mentioned early, a mercenary “in the pay of American imperialism.” Thirty pages later, he is mentioned again when he is recovering from being shot, with no previous context included. Little Chief, a fairly major character, appears in several places in the book, but, again, the episodes are not in chronological order, and the character’s past history is not mentioned. Fortunately, Agualusa, provides a big surprise at the end of the novel – all the characters reappear here and their connections to each other suddenly become clear, regardless of all the time lapses.

Kuvale herdsmen. Today the Kuvale number about 5000 people. Though they were spared most of the warfare of the past 30 years, they occupy a vast area, and suffer from “food poverty.” They are unable to trade their oxen for corn.

Agualusa is an often-enchanting author. Though he pretends that this is a true story, and stresses at the end of the Foreword that this is fiction, he writes his novel as if he really is borrowing directly from Ludo’s diary and directly inhabiting the mind of his “fictional” speaker. His voice quickly becomes hers, and as the action begins, and becomes increasingly real, the reader willingly follows along, allowing Ludo’s voice to lead the way, no matter where it goes and no matter how much a reader might legitimately question details and their “realism.” Ludo, all alone in her apartment for over a quarter of a century, has plenty of time to contemplate Big Issues. As she does this, while also living her life, the narrative swirls, twists backward, then throws itself forward, filled with impressions, memories, and ideas. Having chosen to live apart from the real world, Ludo has essentially disappeared from the earth, and it is no surprise that much of her mental energy is concerned with other disappearances and the memories and the forgetting that are associated with them. Realism and real life become underlying themes of the whole novel, perhaps ironically, since the novel – fiction – deals with real subjects yet much of what we are expected to believe about Ludo is patently unrealistic.

When Ludo’s time in the sealed apartment finally comes to an end, she muses, “I was happy in this home, on those afternoons when the sun came into the kitchen to pay a visit. I would sit down at the table. Phantom would come over and rest his head in my lap. / If I still had the space, the charcoal, and available walls, I could compose a great work about forgetting: a general theory of oblivion.” Ironically, this quotation comes in the middle of the book, long before she goes free, another huge irony on several levels, suggesting once again that Agualusa is reading her diaries and her written musings and then conveying them to us, his/her readers. Surprising novel with unusual energy.

One of the disappearances which Ludo considers is that of an American Airlines 727, unoccupied, which vanished from Luanda’s airport on May 25, 2003. No trace has been found.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.newsweek.com/

The beautiful Ilha Promontory and its beaches are visible from Ludo’s balcony. http://www.embajadadeangola.com

The Kuvale herdsmen have escaped most of the bloodshed of the war against the Portuguese and the war for democratic choice, but they suffer from ‘food poverty,” because they cannot trade their oxen for corn. http://www.gnn.iway.na/

The map of Angola in the south of Africa is from https://www.britannica.com/place/Angola/images-videos

One of the “disappearances” which Ludo considers is that of an American Airlines plane, with no passengers, which vanished on May 25, 2003, thought to have been stolen, and never seen to this day. https://commons.wikimedia.org/