Note: This novel was WINNER of the German Book Prize in 2007.

“[Helene] liked the sweet scent of violets and their delicate appearance, but she admired the upright growth of roses at least as much, the thorns they grew to protect themselves and their bright colours, pink unfolding like dawn, yellow like late October sunlight…Everything about the rose seemed to Helene admirable, even enviable.”

Newly transl ated into English, The Blindness of the Heart, a debut novel by Julia Franck, spans the period between the two world wars in which Germany took part, focusing on the effects of these wars on seemingly ordinary German citizens who were somehow detached from full knowledge of the causes for which they were required to fight. In the dramatic Prologue, which takes place in 1945, a young boy and his mother arrive at a train station from which there is a chance that they might escape the post-war horrors. For the boy, however, the horrors are just beginning. His mother abandons him at the station, without any warning, leaving behind his suitcase and instructions to whoever discovers him on where to deliver him.

ated into English, The Blindness of the Heart, a debut novel by Julia Franck, spans the period between the two world wars in which Germany took part, focusing on the effects of these wars on seemingly ordinary German citizens who were somehow detached from full knowledge of the causes for which they were required to fight. In the dramatic Prologue, which takes place in 1945, a young boy and his mother arrive at a train station from which there is a chance that they might escape the post-war horrors. For the boy, however, the horrors are just beginning. His mother abandons him at the station, without any warning, leaving behind his suitcase and instructions to whoever discovers him on where to deliver him.

The novel focuses on the theme of abandonment throughout its thirty-year time span. Many of the characters abandoned by people they love abandon others, in turn, avoiding responsibility on many fronts. Following the Prologue from 1945, the novel changes its time and focus to the era of World War I. The Wursich family lives in Bautzen, just east of Dresden, on the border between present day Germany and Poland, and just north of Czechslovakia. The personal stories of several members of this family form the backbone of the novel, with the focus on Helene, the youngest daughter of Selma, a housewife with a Jewish background, and Ernst, the owner of a printing company.

Helene is nine years younger than her sister Martha, and is always an outsider in the social action of the family. Her mother has become a voluntary invalid, not in control of her emotions and wanting to be taken care of, after Ernst is drafted to fight in World War I. He is absent from the family for six years, and when he returns, he is a man with little hope for the future, living with a woman who will not leave her bedroom even to speak with him. The children have been on their own for much of that time and have had little or no guidance as they have moved inexorably toward adulthood.

The author provides flashbacks which give some of the background of characters like the parents, Ernst and Selma, in an attempt to show why they have behaved as they have. Ernst had experienced traumas from which he has not recovered. His children, Martha and Helene, have been dealing with the postwar trauma the only way they can, often sleeping together and slipping into erotic comforts to deal with their own uncertainties. When the circumstances at home with their parents reach a crisis, the girls write to their aunt Fanny, who invites them to come to Berlin to live with her, and they quickly abandon their mother and escape to a place that offers more hope.

Reichstag Fire

As Martha escapes reality through the high life offered by her aunt, Helene remains an outsider, hoping to take advantage of opportunities which will help her toward her scholastic goals. Already a nurse at the age of fifteen, she eventually meets Carl, a philosophy student, familiar with the theories of Hegel, Kant, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Cassirer, and she falls in love with him. The economic downturn and the inflation that comes with it, the growing prejudice against the Jews, the difficulties for women who want to achieve highly but have few financial resources, and the everyday problems of working full-time and caring for the child she bears make Helene a kind of “Everywoman,” but her almost total lack of connection with her child and her seeming lack of feeling for him make her a difficult protagonist to like or fully understand.

Critics have praised this novel for its visions of everyday life in Germany during the most difficult times in its history and for its insights into how the Nazis may have come to power while the populace stood by, but the success of the novel depends on whether the reader can fully accept that the Wursich family–Helene, Martha, Helene’s own lovers and husband, and her son–are, in fact, ordinary, everyday people. While the author carefully establishes the physical circumstances that might lead a mother to abandon her child a train station, she is less successful in her ability to show any emotional conflict on the part of the mother, and the ability to abandon a child and never look back strains both sympathy and credulity. The characters’ analyses of the conflict of good and evil (God exists only through pain), their ignorance about the growing political movements, and the economic turmoil only partly justify the extreme actions of some of these characters. The author has created a family with an almost gothic exaggeration of its many weaknesses, and while these characters certainly wring the heart, they are so twisted and damaged–so ready to abandon responsibility–that they are difficult to see as paradigms of everyday German life.

Note: Book clubs should have a lively time analyzing this novel and deciding on whether its realism overcomes the question of gothic exaggeration.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://glareanverlag.wordpress.com/tag/tim-krohn/

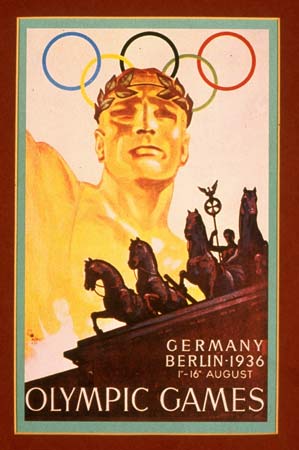

The Reichstag fire (1933) and the Berlin Olympic Games (1936) are part of the atmosphere of this novel. The photo of the Reichstag fire comes from: http://www.visitorinfo.com

The Olympic poster is from: http://www.nelson.usf.edu