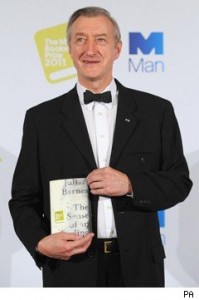

Note: This novel was WINNER of the Man Booker Prize for 2011.

“When you are young, you think you can predict the likely pains and bleaknesses that age might bring…You [can] imagine the loss of status, the loss of desire – and desirability….You may go further and consider your own approaching death….But all this is looking ahead. What you fail to do is look ahead and then imagine yourself looking back from that future point…Discovering, for example, that as the witnesses to your life diminish there is less corroboration, and therefore less certainty as to what you are or have been.”

In one of the most exciting and intellectually stimulating novels of the year, author Julian Barnes tells a two-part story that reconstructs the lives of four young British secondary school students in the 1960s as they study literature and history and argue about philosophy in an effort to solve the riddles of their universe. Through narrator Tony Webster, one of these boys, the author describes their lives up to their early twenties, then leaves them to their fates until Part II begins, forty years later. Webster, now in his sixties, twice divorced and retired, suddenly receives a bequest which suggests hitherto unsuspected revelations about one of his school friends who died young. For forty years, his memories of these school friends and the experiences they shared have informed and affected his life and his philosophy, but now he discovers that the memories may all have been constructed on lies based on incomplete information.

In one of the most exciting and intellectually stimulating novels of the year, author Julian Barnes tells a two-part story that reconstructs the lives of four young British secondary school students in the 1960s as they study literature and history and argue about philosophy in an effort to solve the riddles of their universe. Through narrator Tony Webster, one of these boys, the author describes their lives up to their early twenties, then leaves them to their fates until Part II begins, forty years later. Webster, now in his sixties, twice divorced and retired, suddenly receives a bequest which suggests hitherto unsuspected revelations about one of his school friends who died young. For forty years, his memories of these school friends and the experiences they shared have informed and affected his life and his philosophy, but now he discovers that the memories may all have been constructed on lies based on incomplete information.

As Webster investigates the strange bequest and what it signifies for his life and for his memories of his deceased friend, he also discovers that important documentation, needed to prove the truth about what happened forty years ago, has disappeared, and that the very people who might have been able to answer his questions may be unwilling to do so now. He must decide if he even wants to know about events which may significantly change forty years of memories, his perceptions of others, and other people’s perceptions of him, and despite his curiosity, he is not sure he is ready to accept the challenge.

The novel opens at the school, a college preparatory day school outside of London, with the arrival of Adrian Finn, new to the class and from a broken home (and therefore somewhat “exotic”). Tony Webster has been the intellectual leader of a small group, but Adrian – “book-hungry, sex-hungry, meritocratic, anarchistic” – quickly endears himself to Webster and his two other friends by making a snarky comment when first called upon in class, and he is ushered happily into their midst. “If Alex had read Russell and Wittgenstein, Adrian had read Camus and Nietzsche. I had read George Orwell and Aldous Huxley; Colin had read Baudelaire and Dostoevsky.” Their mutual rites of  passage socially, as they hope to find willing girlfriends and learn for themselves the physical joys of eros and its connections to thanatos (sex and death, as explored conceptually in the philosophy which they have read) combine with their need to impose order on time in their own lives, despite believing in general that time is chaos. “Yes, of course we were pretentious – what else is youth for?…[we] enjoyed saying ‘That’s philosophically self-evident,’ and assured one another that the imagination’s first duty was to be transgressive. Our parents saw things differently.”

passage socially, as they hope to find willing girlfriends and learn for themselves the physical joys of eros and its connections to thanatos (sex and death, as explored conceptually in the philosophy which they have read) combine with their need to impose order on time in their own lives, despite believing in general that time is chaos. “Yes, of course we were pretentious – what else is youth for?…[we] enjoyed saying ‘That’s philosophically self-evident,’ and assured one another that the imagination’s first duty was to be transgressive. Our parents saw things differently.”

After secondary school, Webster meets Veronica, a student who fascinates him, eventually meeting her family in Chislehurst. As time passes, the group goes in different directions, one to work with his father, others to college and, later, travel, but meeting occasionally at the Charring Cross Hotel Bar. Then one of friends stuns the others by committing suicide, without any warning, an event which the remaining three regard as proof of his dedication to his own philosophy and his belief “about the superiority of the intervening act over the unworthy passivity of merely letting life happen to you.” This suicide shows “purity of belief” for Tony and the others in the group, becoming a paradigm of someone who, having experienced the meaninglessness of life has decided that there is no reason to continue living. Instead of “taking his own life,” their friend “took charge of it.” “It’s fucking impressive,” they conclude.

In Part II, forty years later, Tony receives word from a solicitor that he will receive an unexpected bequest of a small amount of money and two documents from someone with whom he has had no contact for forty years. The author uses this interval, as Tony waits to receive these documents, to explore time and history and its relationship with the past. “When we are young we invent different futures for ourselves; when we are old, we invent different pasts for others.” Yet these different pasts for others may change the very memories which we treasure, he comes to discover.

Ultimately, the novel resolves all the complex mysteries of the plot in unexpected ways, and the author’s philosophical musings on life, sex (eros), death (thanatos), and time, their ineradicable connections to our lives, and their more transient connections to our memories are given full play as Barnes also introduces questions of individual responsibility and one’s personal history. Regarding the question of  responsibility, and “whether there’s a chain of it, or whether we draw the concept more narrowly, I’m all for drawing it narrowly…Start with the notion that yours is the sole responsibility unless there’s powerful evidence to the contrary.” In the stunning, dramatic conclusion, Tony Webster explains, “You get toward the end of life – no, not life itself, but of something else: the end of any likelihood of change in that life. You are allowed a long moment of pause, time enough to ask the question: what else have I done wrong?…And I thought of a cresting wave of water, lit by a moon, rushing past and vanishing upstream, pursued by a band of yelping students…There is accumulation. There is responsibility. And beyond these, there is unrest. There is great unrest.” A brilliant, challenging, and ultimately important novel of time, order, and chaos and how we survive.

responsibility, and “whether there’s a chain of it, or whether we draw the concept more narrowly, I’m all for drawing it narrowly…Start with the notion that yours is the sole responsibility unless there’s powerful evidence to the contrary.” In the stunning, dramatic conclusion, Tony Webster explains, “You get toward the end of life – no, not life itself, but of something else: the end of any likelihood of change in that life. You are allowed a long moment of pause, time enough to ask the question: what else have I done wrong?…And I thought of a cresting wave of water, lit by a moon, rushing past and vanishing upstream, pursued by a band of yelping students…There is accumulation. There is responsibility. And beyond these, there is unrest. There is great unrest.” A brilliant, challenging, and ultimately important novel of time, order, and chaos and how we survive.

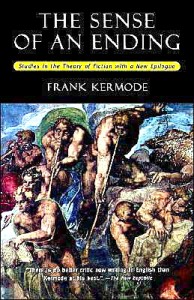

Of particular note is the fact that Barnes has used the same title as a book by famed literary critic Sir John Frank Kermode, whose THE SENSE OF AN ENDING in 1967, revised in 2000, is described on Amazon as “a new epilogue to his collection of classic lectures on the relationship of fiction to age-old concepts of apocalyptic chaos and crisis.” Perhaps Barnes has modeled his book on these concepts as an homage to Kermode.

ALSO reviewed here, Julian Barnes’s THE ONLY STORY

Photos, in order: The author’s photo at the Man Booker presentation is from http://www.asylum.co.uk

The iconic Chislehurst sign, showing Queen Elizabeth knighting Thomas Walsingham in 1597, appears on http://www.guide2bromley.com

The Charing Cross Hotel, where the young friends met for get-togethers is on http://www.cityhotelpictures.com

Tony Webster meets an acquaintance from the past on the Wobbly Bridge which connects the Tate Modern with St. Paul’s.