Note: The Tanizaki Prize is one of Japan’s premier prizes, awarded to a work of fiction or drama each year in honor of author Junichiro Tanizaki (1886 – 1965)

“Please consider, Fukuko: I gave you the man who meant more to me than life itself! And not only that – I gave you everything from that happy household we’d built together as a couple. I didn’t take so much as a broken teacup away with me. I didn’t even get back most of the things I brought with me when I married him!…I’ve been beaten up, knocked down, and trampled on. Considering all I’ve sacrificed, is it too much to ask for one little cat in return?” – letter from Shinako, divorced wife, to Fukuku, new wife.

Irony is too mild a word to describe the twists, surprises, and reversals which bring this book so wildly alive that it is almost impossible to believe the book is not written by a contemporary author. The characters, each of whom is beautifully delineated and brought to life within the limited context of a particular place and imagined time, not only feel real but reflect the universal concerns of human beings around the world, regardless of class or culture. Originally published in 1935-36, the book is as witty, relevant – and, in places, even darkly humorous – as any recent book I can think of, and the novella, from which the book gets its title, and the two stories, with all the imagery they conjure up, constantly reinforce the impression that the author is smirking in the background as we read. Though readers often characterize Japanese literary fiction as being restrained and refined, Tanizaki’s exuberance bursts those bounds and challenges stereotypes, both in tone and in subject matter. In the three stories in this book, he focuses on ordinary people, not aristocrats, trying to get by as well as they can, a focus which allows the author to use colloquial language and write about earthy and sometimes inelegant subjects.

Irony is too mild a word to describe the twists, surprises, and reversals which bring this book so wildly alive that it is almost impossible to believe the book is not written by a contemporary author. The characters, each of whom is beautifully delineated and brought to life within the limited context of a particular place and imagined time, not only feel real but reflect the universal concerns of human beings around the world, regardless of class or culture. Originally published in 1935-36, the book is as witty, relevant – and, in places, even darkly humorous – as any recent book I can think of, and the novella, from which the book gets its title, and the two stories, with all the imagery they conjure up, constantly reinforce the impression that the author is smirking in the background as we read. Though readers often characterize Japanese literary fiction as being restrained and refined, Tanizaki’s exuberance bursts those bounds and challenges stereotypes, both in tone and in subject matter. In the three stories in this book, he focuses on ordinary people, not aristocrats, trying to get by as well as they can, a focus which allows the author to use colloquial language and write about earthy and sometimes inelegant subjects.

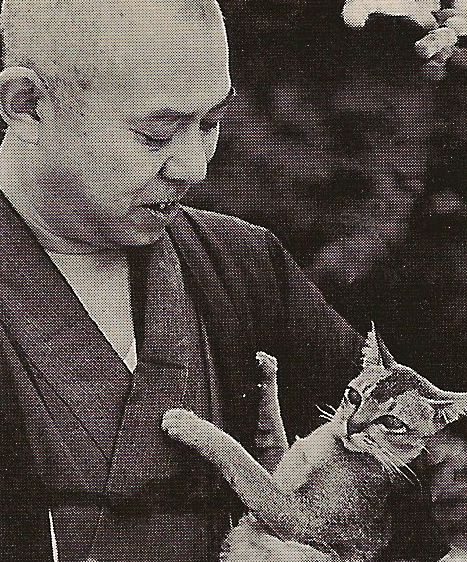

This photo of Tanizaki with his cat appears on the dust jacket of an earlier edition of this novel, published in 1990, by Kodansha.

“A Cat, A Man, and Two Women,” the main selection, features Shozo, a man who has little idea of who he is, no insights at all into the thinking of his family members, and even less ambition, a man manipulated by his mother, his first wife Shinako, and his second wife Fukuku. Each night when he comes home from working at the family shop, he has little to say, spending most of his time relaxing and playing with his cat Lily and expecting to be waited on. Then he feeds Lily mackerel freshly prepared and marinated by his new wife, who doesn’t realize, at first, that she is not really preparing them for her husband. The narrative line moves back and forth, starting with the letter sent by first wife Shinako to new wife Fukuku pleading to have Lily, both as her only keepsake from her marriage and as a pet to keep her company in the town to which she has moved. As the action develops, it reveals the machinations of all the people involved in this story, including the abhorrent behavior of Shozo’s own mother regarding his marriages, and the full weakness of Shozo becomes more obvious. The extremes to which those around him are willing to go in order to get what they want become both amusing and pitiable. The conclusion guarantees that everyone who reads this will conclude, if they don’t already know this from their own experience, that “Cats rule.”

“The Little Kingdom,” a story which raises more thoughtful considerations of themes, begins with the background of Kaijima Shokichi, a thirty-six year-old primary school teacher who has never attained his goals. His father, a specialist in Chinese studies was his idol, and Kaijima always wanted to be a scholar like him. Too late, he realizes he should have been an apprentice in some shop. He is having difficulty supporting his family, and though he has gone to Teachers’ College, he has no advanced study. Unable to cope with pressures of daily life in the city, with his seventh child on the way, he moves to the countryside where he teaches fifth grade. A new student’s arrival begins the action. Soon, this student, Numakura Shokichi, is dominating life on the playground and eventually becomes its “king.” The obvious parallels between this student and a dictator are clear and, considering the story’s date of 1936, it might have been a warning about growing political dangers.

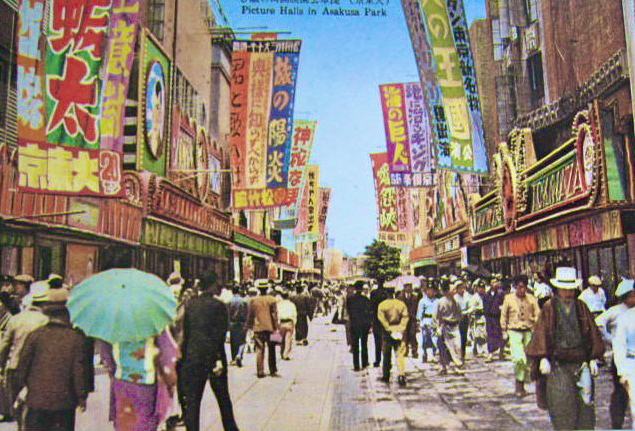

“Professor Rado,” the most bizarre and absurd of the stories, is also the kinkiest. A reporter arrives at Professor Rado’s house for an open-ended interview with him as part of a series called “Visits with Eminent Figures in the Academic World.” When he arrives at twelve-thirty in the afternoon, he learns that the professor is not yet awake. Looking around, the reporter notes the well cared-for garden, the carefully planted azalea bushes, and the smart, but cozy room arrangement in a western style. When Rado finally appears, he does so in clothing so dirty that even the pattern cannot be determined. His eyes are puffy, his flesh is swollen, and he constantly belches. When asked a question, he merely grunts, and when the reporter mentions that he has heard that the professor is leaving his job, he is rebuffed. When the reporter is departing, he glimpses a young girl in nightclothes, bathing, and when he peeks into the professor’s study from the outside, what he sees is shocking, even to him. Several years pass and the reporter, now at the arts desk of the newspaper sees the professor by accident at Asakusa Park, where a variety troupe is performing at one of the theaters. When the reporter speaks to him, the professor asks him for information about one of the dancers. The reporter obliges. Later he learns just how odd the professor’s lifestyle really is.

The reporter finds Prof. Rado at a theater watching a variety troupe in Asakusa Park, years after first meeting him. This photo from 1937 shows what the area looked like before the war.

In this latter story, the twists are particularly strange, and the question of who is the true voyeur or fetishist remains unanswered. Though the professor certainly qualifies for both, the reporter is obviously a voyeur in his actions, and ultimately the reader becomes a voyeur as well. Ultimately, all three stories concern themselves with the subjects of dominance and subservience, with power and how to achieve and use it, and with the psychology which makes dominance over others both possible and plausible. Whether Tanizaki is using a kind of dark humor, as he does in “A Cat, A Man, and Two Women,” a psychological approach as he does in “The Little Kingdom,” or a bizarre erotic interlude, as he does in “Professor Rado,” his themes are similar, his execution is unparalleled, and his characters and their behavior are unforgettable.

ALSO by Tanizaki: SOME PREFER NETTLES, the story of a marriage (1928). DEVILS IN DAYLIGHT, THE MAIDS, IN BLACK AND WHITE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on the back of the book jacket of the 1990 edition this book by Kodansha. A Japanese website says that this photo was taken by famed Japanese photographer Yoshio Watanabe (1907 – 2000).

The Tanizaki House in Kobe was photographed by 663Highland and posted on https://commons.wikimedia.org/

Tanizaki’s study from his memorial museum is seen on http://www.tripadvisor.com/

The theaters in Asakusa Park, where the reporter found Prof. Rado years after first meeting him, appear in this 1937 photo. https://commons.wikimedia.org