“I’ve had a publisher’s request [to write a newspaper novel], and have had to start it quickly. It will be no easy thing for a slow writer like me to keep turning out four pages or so a day for at least the next three or four months. On the average, it’s all I can do to write four pages a day. And so while this newspaper thing is running, I’ll have to spend every day locked up in my study without a break….[and] we won’t know how the game turns out until we play it.”—author Junichiro Tanizaki, from the “Author’s Words in Place of a Preface.”

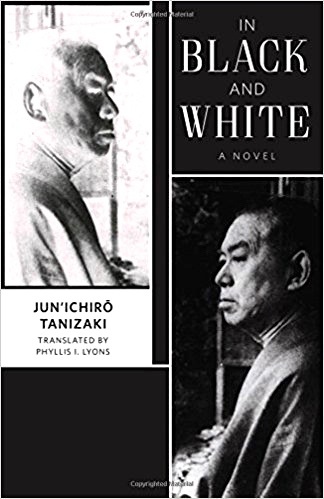

When I saw a reference to this novel by Junichiro Tanizaki as a “new translation,” my attention was pricked, especially when it was described as a book which had been “hidden in plain sight” for over eighty years – a book which even most literary scholars had not heard of until now. As a fan of Tanizaki, I was thrilled by the chance to read an unknown book from 1928 by an author I have always found intriguing – a book which, in translation, would be making history on a world stage. Tanizaki’s well known ability to communicate fully with a broad spectrum of readers, from mystery fans to literary critics, convinced me that this book would connect with readers, and I was not disappointed. In Black and White, a murder mystery set in the late 1920s, provides plenty of excitement, both real and psychological, while also offering some unusual and creative thematic twists on the connections between fiction, reality, and the writing life and its consequences. Here the main character, Mizuno, a writer like Tanizaki, is hired to write a serialized novel for a Japanese newspaper, a task he must begin immediately, and for which he must continue writing every day without major revisions and without allowing the story to fall apart. His eventual story is one in which Mizuno, the writer, chooses one of his “real-life” acquaintances, Cojima, another writer, to be the model for his victim in the fictional murder mystery. Giving him a similar but false name – Codama – within the story, Mizuno then arranges for the fictional Codama, to be murdered as part of the story.

When I saw a reference to this novel by Junichiro Tanizaki as a “new translation,” my attention was pricked, especially when it was described as a book which had been “hidden in plain sight” for over eighty years – a book which even most literary scholars had not heard of until now. As a fan of Tanizaki, I was thrilled by the chance to read an unknown book from 1928 by an author I have always found intriguing – a book which, in translation, would be making history on a world stage. Tanizaki’s well known ability to communicate fully with a broad spectrum of readers, from mystery fans to literary critics, convinced me that this book would connect with readers, and I was not disappointed. In Black and White, a murder mystery set in the late 1920s, provides plenty of excitement, both real and psychological, while also offering some unusual and creative thematic twists on the connections between fiction, reality, and the writing life and its consequences. Here the main character, Mizuno, a writer like Tanizaki, is hired to write a serialized novel for a Japanese newspaper, a task he must begin immediately, and for which he must continue writing every day without major revisions and without allowing the story to fall apart. His eventual story is one in which Mizuno, the writer, chooses one of his “real-life” acquaintances, Cojima, another writer, to be the model for his victim in the fictional murder mystery. Giving him a similar but false name – Codama – within the story, Mizuno then arranges for the fictional Codama, to be murdered as part of the story.

From this plot line, all the remainder of the novel evolves. This newspaper novel, which he ultimately regards as his “Part I” of the story, was considered by critics and readers to be an example of “diabolism” – the belief that devils and their wicked conduct are very real and can interfere in one’s life. Believing that if he wrote a Part II the story might continue, and not incidentally, provide him with even more income, Mizuno writes an outline in which he creates a new scenario in which the real model for Codama is attacked and Mizuno is arrested for the crime. No one believes his innocence. Echoing throughout both versions of the story is a Shadow Man, a devil who may be planning a killing on a moonless Friday, which also happens to be Mizuno’s birthday.

Published by Columbia University Press, the novel contains a translator’s preface by Phyllis I. Lyons to set the scene. A Translator’s Afterword following the conclusion of the novel adds much more information and answers specific questions about the time period, the literary and academic atmosphere of the 1920s, and the state of mind of the author as he began this novel, one of three that he started in 1928 alone. One of the issues raised and discussed in the Afterword is Tanizaki’s own tense relationship with (real) Japanese author, Ryunosuke Akutagawa, author of Rashomon, a man with whom Tanizaki had active disagreements about writing. Akutagawa’s suicide in 1927 may have inspired Tanizaki to write this murder mystery featuring an author as a main character writing about the death of yet another author for which he may feel some sense of responsibility. Akutagawa’s death may also have been responsible for the deeply personal reactions he creates when the main character of this novel, Mizuno, suddenly realizes that “Naojiro Codama,” the false identity he has created for his real model in the novel, slipped briefly from his consciousness as he was finishing a dramatic episode here and he mistakenly referred, on several occasions, to Codama as Cojima, the model’s real name. It is this mistake which causes Mizuno to become frantic with worry that if, by chance, something terrible were to happen to the real Nakajiro Cojima, that the police might see the similarities between that murder and the murder described in his book and think that Mizuno had killed Cojima.

After lying to the clerk about how many pages he has written, receiving payment based on the lie, Mizuno plans a night out, thinking, ironically, of Oishi Kuranosuke, the ideal samurai warrior.

The novel is complex, not only in plot and as it may relate to issues in Tanizaki’s life, but also in overlapping themes, established initially with the title itself. For most readers, the “black and white” references in the title, would refer to issues of morality in which truth competes with lies, and there are plenty of those here, as Mizuno is constantly lying about how much of the novel he has finished, when it will be finished, and about all his creditors. With this novel, the author’s belief in active diabolism, in which a real devil could act on his own, would make the absolutes of truth vs. lies less clear and might explain why Mizuno, who has not committed a murder, somehow feels responsible for committing such a crime or inspiring someone else to do it. His agonizing over the outcome of a simple mistake, which the newspaper publisher does not take seriously, and Tanizaki’s own pre-occupation with the suicide of Akutagawa, seem extreme, under the circumstances.

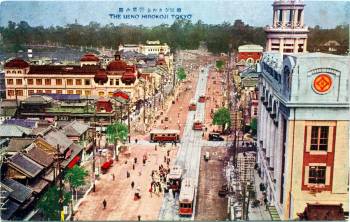

Having received his money under false pretenses, Mizuno heads for the Ueno-Hirokoji intersection for “entertainment.”

Just ten years prior to this novel, Tanizaki wrote another novel, Devils in Daylight, in which truth and reality are also in direct conflict as a man sees what he is sure is a murder taking place, and, more importantly, overhears plans for another such murder a few days later. He hopes to persuade a friend to come with him to observe that murder when it happens. That novel, with its psychological intrigue and its sexual overtones, is more casual, satiric, and filled with ironies, making it very funny and great fun to read. In Black and White is far more serious, with many questions remaining at the conclusion about just what Tanizaki was thinking when he wrote this novel, why he chooses to present the ultimate conclusion as he does, and why the novel has remained virtually unknown in translation.

ALSO by Tanizaki, reviewed here: A CAT, A MAN, AND TWO WOMEN, DEVILS IN DAYLIGHT, THE MAIDS, SOME PREFER NETTLES

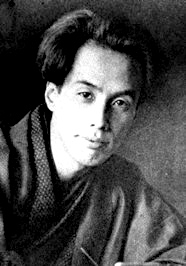

Photos: The portrait of Tanizaki is from http://www.frasesypensamientos.com

The photo of Akutagawa, who committed suicide at the age of thirty-five, appears on https://images.gr-assets.com

Oishi Kuranosuke, regarded as the ideal samurai warrior, comes into Mizuno’s mind as he gets paid under false circumstances and plans a trip to see the ladies. https://images.gr-assets.com/

The intersection of Ueno and Kurokoji beckons to Mizuno as he looks for entertainment after collecting his ill-gotten payment. http://www.oldtokyo.com/