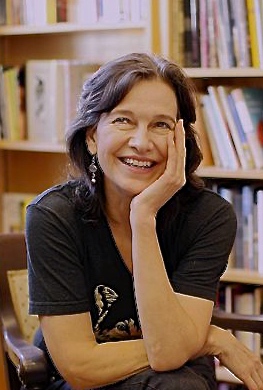

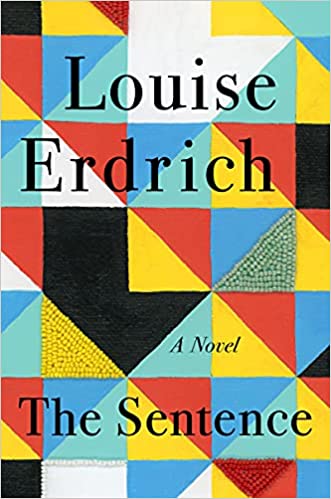

Note: In the past ten years alone, author Louise Erdrich has been WINNER of the Pulitzer Prize, WINNER of the National Book Critics Circle Award, WINNER of the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction, and WINNER of the National Book Award for Fiction,

“When you are haunted, there are no rules. There is no science. You have to do things by instinct because nobody knows how to vanquish a ghost. Most ghost narratives explain away supernatural entities as emotional projections. But Flora had nothing to do with my unconscious. She had ordered me to let her win and was taking me over—penmanship first.”

I have never thought of Louise Erdrich as a particularly humorous author, but the opening chapter of this novel, “Time In Time Out,” had me chuckling nonstop at the wry humor and irony for all thirty pages. Tookie, the narrator, wastes no time introducing herself, explaining in the opening sentence that “While in prison, I received a dictionary. It was sent to me with a note. This is the book I would take to a deserted island,” a book she had received from a former teacher. Tookie, released from prison in her thirties, “still parties, drinking and drugging like I [am] seventeen,” and she admits that she does not yet know who she is. Not beautiful on the outside, she admits to not being beautiful on the inside, either, confessing that she enjoys lying and selling people useless things for prices they can’t afford.” Her past crime occurred when Budgie, the husband of her friend Mara, died suddenly, and both Mara and another friend, Danae, who was also in love with Budgie, were determined to claim his body to give it a “proper” burial. Each one was also determined that she and she alone would be recognized as the true love of Budgie. As it happened, one of them had just been a big winner at the casino, and she offered Tookie the entire amount of the win if Tookie would steal the body and bring it to her. When she did this, however, Tookie was arrested by a tribal policeman for a serious federal crime involving the body, and she was eventually sentenced to sixty years in prison, later reduced to seven years served. Even with all these horrors, most readers will still be smiling.

I have never thought of Louise Erdrich as a particularly humorous author, but the opening chapter of this novel, “Time In Time Out,” had me chuckling nonstop at the wry humor and irony for all thirty pages. Tookie, the narrator, wastes no time introducing herself, explaining in the opening sentence that “While in prison, I received a dictionary. It was sent to me with a note. This is the book I would take to a deserted island,” a book she had received from a former teacher. Tookie, released from prison in her thirties, “still parties, drinking and drugging like I [am] seventeen,” and she admits that she does not yet know who she is. Not beautiful on the outside, she admits to not being beautiful on the inside, either, confessing that she enjoys lying and selling people useless things for prices they can’t afford.” Her past crime occurred when Budgie, the husband of her friend Mara, died suddenly, and both Mara and another friend, Danae, who was also in love with Budgie, were determined to claim his body to give it a “proper” burial. Each one was also determined that she and she alone would be recognized as the true love of Budgie. As it happened, one of them had just been a big winner at the casino, and she offered Tookie the entire amount of the win if Tookie would steal the body and bring it to her. When she did this, however, Tookie was arrested by a tribal policeman for a serious federal crime involving the body, and she was eventually sentenced to sixty years in prison, later reduced to seven years served. Even with all these horrors, most readers will still be smiling.

What follows is a story of Native American characters with long histories in Minnesota, dealing with legal and cultural issues with historical roots. Author Louise Erdrich, an enrolled member of the Chippewa tribe, has not only observed history but has lived through it, and her insights into critical events of the past two years in Minnesota, especially, are part of this novel, with Tookie the person who comes to life through them. Tookie’s release from prison in 2005, left her in great need of a job, but her only real qualification was that she had read virtually everything in the prison library – every one of the Great Books, and even pop and graphic novels. It is not until she eventually talks to “Louise,” the bookshop’s owner, that she is able to get a job in this “dark time for little bookstores.” (Author Louise Erdrich owns Birchbark Books in Minneapolis, and the implications here are obvious.) It is through this job that Tookie first meets Flora, an older white woman who claims that she has Native roots for which she is still doing research, a common claim by white people who long for the history which accompanies true Native ancestry.

The Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe,. NM, is where Hetta has attended school, briefly.

Flora dies in her sleep shortly after their meeting, however, and when Flora’s daughter Kateri donates to the bookshop the ancient tome of Native history that Flora was reading at the time of her death, her association with Tookie and the bookshop are made irrevocable. The book, The Sentence: An Indian Captivity 1862 – 1883, details the Dakota War of 1862, its sorrows, and its aftereffects, and it gives Flora a place to “live” at night. As the characters and their unusual stories begin to develop, their extended families and friends also gain interest. Flora, before her ghost life, fostered native runaways and raised money for a Native women’s refuge. Pollux, Tookie’s husband, is the former policeman who originally arrested her for stealing a body and sending her to jail. He now works as a woodworker and is her loving husband. His niece/adopted daughter, Hetta, has left school at the Institute for Native American Arts, after privately making a pornograpic movie for which she is ashamed. Her baby son, Jarvis, however, has become the light of everyone’s life.

Then Covid strikes, affecting everyone. Louise is doing readings at the Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, Kansas, even though her bookstore at home in Minneapolis may have to be closed because of Covid, when she gets messages to return home. Friends and family there feel that “death is in the air.” She returns, and things seem to be going downhill, with some residents and friends returning to drinking and bad habits that they had overcome. The saving grace, however, seems to be that books are part of their lives, and references to books, authors, and perfect novels are named throughout the narrative, even as Louise becomes despondent at her store’s expected closing. She succeeds, however, in gaining “essential worker” status for her employees, and it remains open. Sadly, and independently, Tookie begins to fear the ghost of Flora even more, as she is unable to free herself from Flora’s influence, and Flora has become violent, trying to get inside her body.

The death of George Floyd in Minneapolis a few months later leads many of the characters and their friends to identify with the black demonstrators against the police, whom they regard as behaving like military enforcers. Buildings burn, people are beaten, and giant armored Humvees control the streets. There are “pockets of peace,” however. There is about an acre of full grocery bags behind a church to be distributed, people continue planting gardens, and people are painting vibrant paintings on the boarded up windows of stores. And they were frantic at the bookstore. “Everyone who wasn’t out on the streets wanted to read about why everyone else was out on the streets. Orders kept coming for books about police, racism, and history.” People needed books – of all kinds – for refuge, and many lists of them are provided here. Ultimately, the importance of the word – and the sentences made from those words – become the theme of the novel, a way for readers to think in new directions, experience new ideas, and, perhaps change from within during times of almost unimaginable crisis.

ALSO by Erdrich: LAROSE, THE PAINTED DRUM, THE ROUND HOUSE, SHADOW TAG

Photos. The photo of Birch Bark Books, owned by author Louise Erdrich, comes from https://streets.mn

The Institute for American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, NM appears on https://www.expedia.com

Haskell Indian Nations University where Louise was speaking as Covid became a major issue, is shown here: https://lawrencekstimes.com

The George Floyd poster may be found on https://www.msnbc.com

The author photo is from https://www.chicagotribune.com