“I am lost, adrift, stumbling through a world I do not understand. I hear a rustle in the undergrowth and can’t decide if it’s a jaguar stalking with ominous restraint or an LBJ scratching for worms. I find succulent globes of fruit but don’t dare touch them for fear of poison…. I am as stupid as a child.”

Jenny Dunfree gets her first hint of some of the difficulties she will face during an ornithological research project in the San Blas Islands, off the coast of Panama, when the ticket agent at the airport refuses to sell her a one-way ticket. Insisting that she does not want to return the following day, Jenny is unable to convince anyone at the airport that she will stay on Sugatupu for an extended period of time. Her duties, funded by a foundation, are to study a nest of harpy eagles, a rare species, and keep notes on their behavior, their feeding habits, and any eaglets which may appear. Exhausted when she finally makes her way to Sugatupu by canoe, she is immediately accosted by a young boy who drags her through the night-time forest to the village meeting house. There, she must list her genealogy for the village elders. She is not allowed to tell her own name, however, nor is anyone else allowed to ask it. “Without a name, do I have a soul? Am I a real person?” she wonders.

Dunfree gets her first hint of some of the difficulties she will face during an ornithological research project in the San Blas Islands, off the coast of Panama, when the ticket agent at the airport refuses to sell her a one-way ticket. Insisting that she does not want to return the following day, Jenny is unable to convince anyone at the airport that she will stay on Sugatupu for an extended period of time. Her duties, funded by a foundation, are to study a nest of harpy eagles, a rare species, and keep notes on their behavior, their feeding habits, and any eaglets which may appear. Exhausted when she finally makes her way to Sugatupu by canoe, she is immediately accosted by a young boy who drags her through the night-time forest to the village meeting house. There, she must list her genealogy for the village elders. She is not allowed to tell her own name, however, nor is anyone else allowed to ask it. “Without a name, do I have a soul? Am I a real person?” she wonders.

Jenny is expected to appear at the village meeting house every Saturday evening, without fail, though she does not speak the Kuna language of her Indian hosts, and most of them speak little or no Spanish. Living as isolated as possible from the rest of Panama, the Kuna Indians have their own culture, thousands of years old, and the biggest influences (and some of their biggest problems) have come from missionaries who have wanted to change their beliefs about the world, impose a new system of morality, redefine the nature of good and evil, and educate the Kuna children in missionary schools away from the island. They love nature and believe in a spirit world which includes all animals, plants, and even rocks, and they understandably resent the intrusions of those who would change their ways of life.

Because Jenny obviously appreciates nature, which is the basis of all the Kuna beliefs, she is watched over and somewhat protected by the Kuna. San Blas has also been recognized as a dropping point for cocaine, and Jenny has become friends with a white man who sometimes shows up to chat with her, armed with a pistol. As her research work continues, she becomes more and more convinced that the eagles that she is observing are not harpy eagles at all, a fact that could jeopardize the whole project.

Because Jenny obviously appreciates nature, which is the basis of all the Kuna beliefs, she is watched over and somewhat protected by the Kuna. San Blas has also been recognized as a dropping point for cocaine, and Jenny has become friends with a white man who sometimes shows up to chat with her, armed with a pistol. As her research work continues, she becomes more and more convinced that the eagles that she is observing are not harpy eagles at all, a fact that could jeopardize the whole project.

Author Louise Young, herself an ecologist who began working in the San Blas islands in 1996, had intended this book to be a National Geographic-style travel piece in which she used the voice of an “armchair anthropologist,” but she says she eventually found that a fictionalized anthropological framework worked better. “Fiction became my tool to muscle stick-figure stereotypes into the array of personalities that inhabit all human communities,” she says. Her characters are, in fact, often stereotypes, but she succeeds in creating a broad picture of the Kuna culture she is depicting because the culture itself is so interesting.

It is twenty-five-year-old Jenny who is the most annoying stereotype, a woman with an advanced degree who is depicted, primarily, as a woman, and only secondarily as an ecologist, anthropologist, and scientist. Jenny has romantic and unrealistic visions of her role at the outset, and she appears to be sexually attracted (quite often) to a number of the village men, disregarding any sense of detachment about her supposed role. She cries a lot, frequently uses the kind of profanity common among young college students, smokes dope when she has the opportunity, and is “saved” on a regular basis by the men who feel the need to protect her.

The novel becomes deeper as it progresses, and the reader’s fascination with the culture grows. Ultimately, it is Jenny’s respect for the culture and beliefs which make the novel work. Though it is clear that some aspects of the culture of these islands will inevitably change, the author’s own work there as a “cultural guide” and “technical advisor to a women’s cooperative” will help preserve the essence of their way of life.

The novel becomes deeper as it progresses, and the reader’s fascination with the culture grows. Ultimately, it is Jenny’s respect for the culture and beliefs which make the novel work. Though it is clear that some aspects of the culture of these islands will inevitably change, the author’s own work there as a “cultural guide” and “technical advisor to a women’s cooperative” will help preserve the essence of their way of life.

Notes: The author’s photo appears on her Amazon Author page.

The map of Panama, showing the San Blas Islands on the Atlantic coast, is from: www.tropicaldiscovery.com

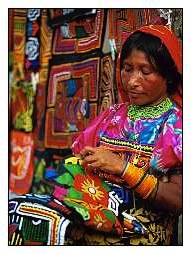

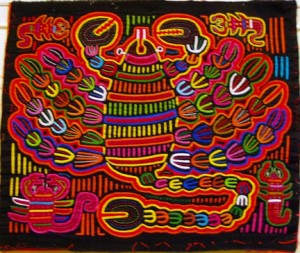

The women of the San Blas Islands are famous for making molas, elaborate cutwork of abstract designs from nature, which they use on the front and back of their blouses. The lobster mola, shown here, is from the Museum of Quilts and Textiles in San Jose. Molas are made by piling up individual layers of colored cloth, in this case at least nine different layers: Working with only a razor blade or a small pair of scissors and a needle and thread, [the maker cuts through layers until she reaches the color she wants, and then hems around it], creating some of the most intricate stitchery found anywhere on earth. www.turq.com

Author Louise Young, whose own quilt work is in museums, gives tours to the these islands. www.molatour.com Her blog is here: www.redroom.com.