“I felt the heat of my fever. I was bleeding and crying at once. The kicks continued to rain on me where I was lying, [my arms handcuffed behind my back]….As soon as I was up, another kick brought me down on my face…I tried to stand, but failed. One of the torturers helped me up this time. He then attached my handcuffs to something and I felt a pull. Soon I was suspended from the ceiling. I screamed inside my hood with all of my might.”

Iraqi schoolteacher Mustafa Ali Noman has spent his life avoiding Saddam Hussein’s military, the Baath Party, and controversy in general. Happily married and the father of a young son and daughter, he and his wife are, for the first time, in a position to build a house, which he inspects on weekends, now that the house is close to completion. After leaving school for an hour to pay the final bill to the contractor, Noman returns to his class, but he is arrested by two Security officials as soon as he returns, taken to prison for interrogation, and slapped around:

—Mustafa Ali Othman?

I shook my head.

—No, my name is Mustafa Ali Noman.

—Makes no difference….You deny using an assumed name? Your name is Mustafa Ali Othman.

—But that’s an error. As I’ve said, my name is Mustafa Ali Noman.

—Take him out of here.

It is 1979, and Noman knows that “sooner or later, everyone is liable to run afoul of the regime or be mistaken for someone who has. Being free only means one thing: imminent arrest.” Though he is completely innocent, Noman spends the next year being moved from prison to prison, where he and those with him are tortured by some of the most painful methods ever devised. As Noman moves around the country, he observes that ninety-nine percent of those arrested, tortured, or executed are completely innocent, yet none can prove their innocence since all are assumed to be liars from the outset. The best any innocent person can hope for is a lighter sentence, and lighter abuse, until his eventual release, weeks, months, or years hence–if he survives prison at all. As one of eighteen men in a cell measuring six by eight feet, Noman asserts that “despite the exhaustion, restraints, and reduction of my humanity to the banality of a mere number, I found myself in a space suffused with human warmth. These men might have violated the laws of society or they might have been criminals from the point of view of the state, but I believed in their innocence partly because I knew my own and partly because they received me with open arms; I felt I was one of them.”

It is 1979, and Noman knows that “sooner or later, everyone is liable to run afoul of the regime or be mistaken for someone who has. Being free only means one thing: imminent arrest.” Though he is completely innocent, Noman spends the next year being moved from prison to prison, where he and those with him are tortured by some of the most painful methods ever devised. As Noman moves around the country, he observes that ninety-nine percent of those arrested, tortured, or executed are completely innocent, yet none can prove their innocence since all are assumed to be liars from the outset. The best any innocent person can hope for is a lighter sentence, and lighter abuse, until his eventual release, weeks, months, or years hence–if he survives prison at all. As one of eighteen men in a cell measuring six by eight feet, Noman asserts that “despite the exhaustion, restraints, and reduction of my humanity to the banality of a mere number, I found myself in a space suffused with human warmth. These men might have violated the laws of society or they might have been criminals from the point of view of the state, but I believed in their innocence partly because I knew my own and partly because they received me with open arms; I felt I was one of them.”

Saddam’s regime arrests anyone who whispers anything derogatory about the regime, even in the “privacy” of his own home; or who makes even a simple joke; or who has not joined the Baath party, one responsibility of which is to report on members of the family or friends on a weekly basis. Children are forced to tell stories about family members, and Noman is in jail with a young child, still hugging his blanket, and his uncle. The child had been forced to betray the innocent uncle after Security killed one of the child’s acquaintances before his very eyes and threatened to torture the child to death. Both are scheduled to be executed. A young teenager who happened not to be carrying his birth certificate or draft card, is one of many who have been arrested, tortured, and raped. Women, young children, and the elderly meet the same fate. Even the loss of a license plate is enough to be arrested and held for unlimited periods of time. People of Iranian descent are particularly vulnerable since the war between Iran and Iraq is looming, and many have registered as Iranian as a way to save their sons from the Iraqi draft. The fact that they are usually Shias while Saddam is Sunni makes them additionally suspect.

Saddam’s regime arrests anyone who whispers anything derogatory about the regime, even in the “privacy” of his own home; or who makes even a simple joke; or who has not joined the Baath party, one responsibility of which is to report on members of the family or friends on a weekly basis. Children are forced to tell stories about family members, and Noman is in jail with a young child, still hugging his blanket, and his uncle. The child had been forced to betray the innocent uncle after Security killed one of the child’s acquaintances before his very eyes and threatened to torture the child to death. Both are scheduled to be executed. A young teenager who happened not to be carrying his birth certificate or draft card, is one of many who have been arrested, tortured, and raped. Women, young children, and the elderly meet the same fate. Even the loss of a license plate is enough to be arrested and held for unlimited periods of time. People of Iranian descent are particularly vulnerable since the war between Iran and Iraq is looming, and many have registered as Iranian as a way to save their sons from the Iraqi draft. The fact that they are usually Shias while Saddam is Sunni makes them additionally suspect.

Told in an almost journalistic style, author Mahmoud Saeed, who himself was arrested and jailed for a year in 1963 and rearrested five more times after that–up to 1980–uses his personal observations and his own feelings to pay witness to the horrors of Saddam Hussein’s regime. His concise and straightforward style allows the reader to develop an emotional connection with the characters on his/her own, and sets Saeed’s feelings, noticeable throughout, into sharp relief. By having Noman, a Basra resident, transferred from southern Iraq to prisons as far north as Irbil and Sulaymaniah, where five thousand Kurds suffered genocide, the author can show that the horrors and war crimes are widespread. In some ways, reading this novel feels like reading Kafka, but the absurdities faced by Gregor Samsa and Josef K are frivolous compared to what Saddam Hossein forced upon his people. War crimes take on a whole new meaning as “Noman” becomes an Everyman, suffering unjustly.

ALSO by Mahmoud Saeed: THE WORLD THROUGH THE EYES OF ANGELS

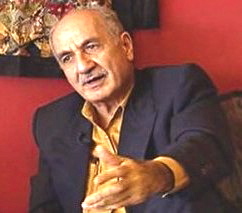

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears with a brief bio on www.sundaysalon.com , a news site from New York, Nairobi, and Chicago.

The photo of the prison at Sulaymaniah, where Noman was held at one point, shows the last of Saddam’s war materiel outside. The photo is by Bob Keith and appears on http://gazettextra.com, which also shows additional photos of Iraq. This is the prison in which 5000 Kurds and others were executed.

In a touching–even miraculous–development, this prison has now been converted into a memorial to the Kurds and those others executed there by Saddam Hussein. The final photo, also by Bob Keith, shows its marvelous transformation. The front entrance to the prison, once all concrete and brutal efficiency, now contains intricate, carved glass panels which project out from the walls and ceiling, with tiny lights illuminating the glass. Each of these tiny lights is supposed to memorialize one of the people executed in this prison. http://gazettextra.com Some of the cells have remained exactly as they were left so that no one ever forgets.