“I have written more than twenty novels, and usually the writing of a novel requires a year or more of thought, but I did not think much about this novel. The idea came to me like a meteor shining in the sky. Last year [around 2005] I went to Tijuana, Mexico…and there in Tijuana I saw things that reminded me of Mosul in the summer…I began to write this book in Mexico and finished writing it in Chicago, to serve as a living witness to a people fated to walk in bitter darkness.” –Mahmoud Saeed

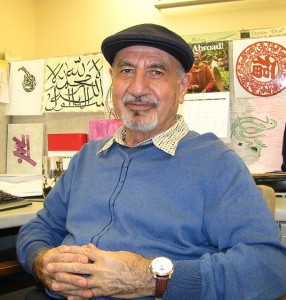

If ever there were someone who had a right to be angry and bitter about the fate of Iraq and its intellectuals, Mahmoud Saeed has that right. Arrested and jailed for a year and a day in 1963, when he was twenty-four, and again five more times after that, through 1980, he was never again to see any of his books published in Iraq, and two of his manuscripts were burned by authorities. Yet even through his imprisonment, described in Saddam City, he retained his ability to see humanity and hope, saying, “Despite the exhaustion, restraints, and reduction of my humanity to the banality of a mere number, I found myself [sharing a cell that was] suffused with human warmth. These men might have violated the laws of society or they might have been criminals from the point of view of the state, but I believed in their innocence partly because I knew my own and partly because they received me with open arms; I felt I was one of them.” The author seems to have no agenda, other than the desire to share what he has discovered about the abiding humanity of the people he has known, and the reader responds to him with the same kind of warmth.

If ever there were someone who had a right to be angry and bitter about the fate of Iraq and its intellectuals, Mahmoud Saeed has that right. Arrested and jailed for a year and a day in 1963, when he was twenty-four, and again five more times after that, through 1980, he was never again to see any of his books published in Iraq, and two of his manuscripts were burned by authorities. Yet even through his imprisonment, described in Saddam City, he retained his ability to see humanity and hope, saying, “Despite the exhaustion, restraints, and reduction of my humanity to the banality of a mere number, I found myself [sharing a cell that was] suffused with human warmth. These men might have violated the laws of society or they might have been criminals from the point of view of the state, but I believed in their innocence partly because I knew my own and partly because they received me with open arms; I felt I was one of them.” The author seems to have no agenda, other than the desire to share what he has discovered about the abiding humanity of the people he has known, and the reader responds to him with the same kind of warmth.

Even stronger feelings are evoked in The World Through the Eyes of Angels. Obviously autobiographical, at least in part, the novel examines the various kinds of love which a young boy from Mosul discovers as a youth, sweeping the reader along on a tide of empathy and making him/her feel at one with the main character. Providing wonderful insights into the lives and cultures of the main characters – Muslim, Christian, and Jewish – many of whom are friends of the young boy and his family, The World Through the Eyes of Angels is aimed directly at the heart without a shred of easy sentimentality. The interactions and emotions the characters share are so universal that the novel feels as if the characters are people we know, or would like to know, despite the differences of time, culture, and tragic history. Politics plays no role here. Best of all, the novel possesses that rare ability to connect with the reader so directly that it provides insights into the heart and mind of the author, too, and when one reaches the end of the novel, it is impossible not to want to offer comfort.

Even stronger feelings are evoked in The World Through the Eyes of Angels. Obviously autobiographical, at least in part, the novel examines the various kinds of love which a young boy from Mosul discovers as a youth, sweeping the reader along on a tide of empathy and making him/her feel at one with the main character. Providing wonderful insights into the lives and cultures of the main characters – Muslim, Christian, and Jewish – many of whom are friends of the young boy and his family, The World Through the Eyes of Angels is aimed directly at the heart without a shred of easy sentimentality. The interactions and emotions the characters share are so universal that the novel feels as if the characters are people we know, or would like to know, despite the differences of time, culture, and tragic history. Politics plays no role here. Best of all, the novel possesses that rare ability to connect with the reader so directly that it provides insights into the heart and mind of the author, too, and when one reaches the end of the novel, it is impossible not to want to offer comfort.

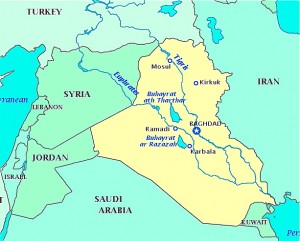

Divided into twelve parts, the novel is set in Mosul in the 1940s and 1950s, “when the people lived as brothers in total harmony as if they were one family,” despite their varied cultures. The boy, named once in the novel as “Saleh,” lives in poverty but, from the age of four, does errands for his much older brother, a sadistic egotist whom the boy privately calls Ahmad the Mad Dog. Often beaten and tormented by this brother, he runs barefoot all day long throughout the city, even when the temperatures reach 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Gradually, the reader comes to know the boy, his family, and his friends, especially Sami, a Jewish boy, who loves to tell the boy stories from the movies which the boy does not see.

Divided into twelve parts, the novel is set in Mosul in the 1940s and 1950s, “when the people lived as brothers in total harmony as if they were one family,” despite their varied cultures. The boy, named once in the novel as “Saleh,” lives in poverty but, from the age of four, does errands for his much older brother, a sadistic egotist whom the boy privately calls Ahmad the Mad Dog. Often beaten and tormented by this brother, he runs barefoot all day long throughout the city, even when the temperatures reach 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Gradually, the reader comes to know the boy, his family, and his friends, especially Sami, a Jewish boy, who loves to tell the boy stories from the movies which the boy does not see.

The best stories the boy hears, however, come from Sheikh Ahmad Al-Shadi, who claims to be one hundred twenty-seven years old and who tells stories about the sheikh and the wolves, about the sheikh and the thief, about history, including the training of women to use bows and arrows so they can fight against 450,000 Persians, and about the Siege of Mosul. The speaker does not know whatever became of this beloved sheikh – he lost track of him when he went to school, where he was mentored by a teacher who discovered that he seemed to be able to read without ever having been taught.

The first love story takes place when the boy discovers Selam, a little girl whose mother is dying, and who is so poor they have absolutely nothing in the “house” where they live. Though poor himself, the boy surprises her with little presents from the tiny amounts he earns and teaches her reading and numbers in his spare time. Later, the older Madeleine, “a treasure that enriched my spirit,” teases him outrageously, teaching him about sexuality, though he is not sure what it all means. Through Mary, he enters a church for the first time, and later still, Sami’s sister Sumaya shows him a new side of family life and love.

The first love story takes place when the boy discovers Selam, a little girl whose mother is dying, and who is so poor they have absolutely nothing in the “house” where they live. Though poor himself, the boy surprises her with little presents from the tiny amounts he earns and teaches her reading and numbers in his spare time. Later, the older Madeleine, “a treasure that enriched my spirit,” teases him outrageously, teaching him about sexuality, though he is not sure what it all means. Through Mary, he enters a church for the first time, and later still, Sami’s sister Sumaya shows him a new side of family life and love.

Throughout, the author artfully recreates the real lives of real children, and as the time frame moves back and forth, up to 1964, when the speaker is released from prison and decides to go to Morocco to teach, t he stories and their aftermaths continue. The love stories involve a young boy, but they are real love stories, complicated by the times and circumstances in which they all live. Some have no endings, something the speaker (and, one cannot help thinking, the author) mourns at the end of the book, and some have endings that are not happy.

he stories and their aftermaths continue. The love stories involve a young boy, but they are real love stories, complicated by the times and circumstances in which they all live. Some have no endings, something the speaker (and, one cannot help thinking, the author) mourns at the end of the book, and some have endings that are not happy.

This is a difficult book to summarize, since parts of it, taken out of the overall context may sound as if they are romanticized or sensationalized. They are not – the novel is intimate and honest, the story earnest in its appeal. The author never gives any details at all about the speaker’s arrest and imprisonment, something that the reader cannot help wondering about but which would have changed the focus of the novel. The girls/women with whom the speaker learns about love seem, generally, as innocent as he is, all of them part of the well-described cultures in which they live. A nd the sense of loss, as people from various groups, once integrated into the city, move out of Mosul, leaves the reader with a feeling of gratitude to the author for preserving, historically, everything he remembers of the past through his characters here. Though the author/speaker expresses regrets for some aspects of his life, those of us of a similar age will understand and empathize with these all-too-human regrets.

nd the sense of loss, as people from various groups, once integrated into the city, move out of Mosul, leaves the reader with a feeling of gratitude to the author for preserving, historically, everything he remembers of the past through his characters here. Though the author/speaker expresses regrets for some aspects of his life, those of us of a similar age will understand and empathize with these all-too-human regrets.

ALSO by Mahmoud Saeed: SADDAM CITY

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://en.wikipedia.org

The Iraqi boy, about the age of the speaker, appears here: http://www.army.mil

The Iraqi girl, about the age of Selam, appears here: http://web.worldbank.org

The Al-Hadbas minaret, seen from the Umayyad Mosque, is from http://www.picsearch.com

The map of Iraq appears on http://www.yourchildlearns.com