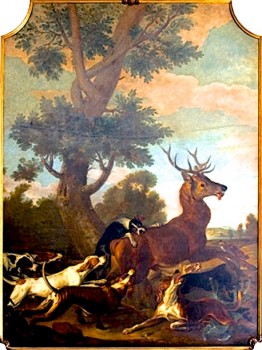

“All of art rests in the gap between that which is aesthetically pleasing and that which truly captivates you. And the tiniest thing can make a difference. I had only to set eys on the painting and a sensation came over me: you might describe it as butterflies, but in fact for me it’s less poetic. It happens every time I feel strongly drawn to a painting.” Speaker upon first seeing the painting of ‘Dreux’s Deer’ for the first time.

In Optic Nerve, Argentinian author Maria Gainza’s narrator invites the reader into her life to share her love of art – paintings which inspire the glorious feelings which come to her, often suddenly, when she sees something unique in a painting and suddenly connects with it emotionally. These unexpected moments add thrills to her life, joining her spiritually with the people and places associated with the art. As she muses on these moments in this collection of stories of her life, she allows her mind and its associations free rein. Although this is a novel, the effects of the special paintings on the speaker are so vivid that they seem real and personal, revealing, over the course of the novel, all aspects of the narrator’s life over many years and her growing understanding of life’s ultimate themes – the unique ways in which we, as individuals see and feel life and death, good and evil, beauty and ugliness. Time in these stories is flexible, as the speaker jumps from one time and place to another, sometimes across centuries and continents, following a thread of memory which ties it to a painting and the speaker’s past.

In Optic Nerve, Argentinian author Maria Gainza’s narrator invites the reader into her life to share her love of art – paintings which inspire the glorious feelings which come to her, often suddenly, when she sees something unique in a painting and suddenly connects with it emotionally. These unexpected moments add thrills to her life, joining her spiritually with the people and places associated with the art. As she muses on these moments in this collection of stories of her life, she allows her mind and its associations free rein. Although this is a novel, the effects of the special paintings on the speaker are so vivid that they seem real and personal, revealing, over the course of the novel, all aspects of the narrator’s life over many years and her growing understanding of life’s ultimate themes – the unique ways in which we, as individuals see and feel life and death, good and evil, beauty and ugliness. Time in these stories is flexible, as the speaker jumps from one time and place to another, sometimes across centuries and continents, following a thread of memory which ties it to a painting and the speaker’s past.

The “chronology” of these memories, or lack of it, is clear from the first episode,“Dreux’s Deer.” Here the speaker finds herself in Belgrano, a section of Buenos Aires, after she has been hired to take two tourists to see an art collection in an enormous private home. Arriving late because she has been caught in a deluge along the way, she is drenched and disheveled when she arrives, and the owner of the house looks at her with incredulity, wondering why this person has been hired to do a job which she believes she herself could have done better and with more finesse. When the speaker is unable to answer questions about horses in a hunting scene by Alfred de Dreux (1810 – 1860) on the tour, the painting’s owner makes snide remarks. The speaker, however, regards that painting as simply “decorative” and “conventional,” evading the owner’s sarcasm about a painting which she considers unimportant. After this memory, she expands the story, telling the reader that five years later she saw, for the first time, a painting of a deer hunt by the same Alfred de Dreux, and this time her reaction was “fireworks, what A. S. Byatt called ‘the kick galvanic’.”

“Dreux’s Deer,” by Alfred de Dreux, unknown date, 19th century.

Further describing this experience as a reaction to dopamines being released in the brain, observations she attributes to the author Stendahl, she goes on to recall Dreux’s background as a child model for artist Theodore Gericault (1791-1824), briefs the reader on who Dreux was and who Gericault was, then describes hunt paintings in general, flashing back to Gothic art of the Middle Ages. In the Dreux painting, the deer is trying unsuccessfully to evade the teeth of the hunting dogs, something the speaker sees as the “atavistic symbolism” of Dreux’s work: “the struggle between good and evil, light and dark.” This scene ultimately reminds the speaker of something that happened in her own life three years ago, when one of her friends from university was visiting a sister in France and was killed, accidentally shot during a hunt at the sister’s chateau. In conclusion, she admits that she does not know why she is mentioning this “ridiculous” death now, and concludes, casually, that “You write one thing in order to talk about something else.”

Following this “flexible” pattern, the speaker wanders through her most vivid memories of some of the paintings and artists that have dramatically affected her life, works which vary significantly in style and time period. Argentinian artist Candido Lopez (1840-1902) is described while he is at work on the battlefields during the war between Paraguay and an alliance of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay from 1864 – 1870. When his work is eventually sold to the Museum of National History in Buenos Aires, a guard reports that it is accompanied by ghosts in white uniforms, an image which lingers during a later description of the speaker’s marriage in the same chapter. “The Enchantment of Ruins,” by Hubert Robert (1733-1808), who specialized in painting ruins as part of the “aesthetics of decay,” reminds the speaker of a quotation from Truman Capote at age twelve: “The world was…unlasting, what could be forever?” And in “Lightning at Sea,” Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) establishes a style of realism which aims at saturating the senses. Later in that same story the speaker connects “the saturation of the senses” with the life of her cousin, whom she believes is mad.

“Out of the Traps” features Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (1864 – 1901), whose work was discovered at the museum by the young speaker who never “got into Monet’s style.” “A Life in Pictures” tells of a person in a doctor’s waiting room, terrified by an issue involving her eyesight, who sees a picture by Mark Rothko (1903-1970). The story of Rothko’s life alternates with the speaker’s own issues, her husband’s critical illness, and his good response to a copy of a Rothko painting which she brought to him. Henri Rousseau (1844 – 1910) appears in “The Hills from Your Window,” and Augusto Schiavoni is featured in “To Be a Rapper.”

Gainza adds depth to her art focus with references to famous writers, including their comments on art throughout the book. A. S. Byatt, Giuseppe di Lampedusa, Truman Capote, Guy de Maupassant, Victor Hugo, and Carson McCullers are quoted here, and other writers, like Katherine Mansfield, Somerset Maugham, Nikolai Gogol, and J. D. Salinger are referenced.

It is easy to imagine a reader who loves art and literature becoming totally engaged in these stories of artists and and their lives around the world, with many episodes from the speaker’s life also connecting to them – in the author’s mind, at least. Indicating in one place that her name is Maria, a name she shares with the author, the narrator tells her stories with imagery so vibrant it suggests that this novel may be memoir, at least as much as it is fiction, and as the personality of the speaker evolves peripherally, the reader becomes intrigued with author Gainza as well. Ultimately, a reader is reminded of the book’s epigraph by Joseph Brodsky for the most insightful commentary on its ideas: “The visual aspect of life has always been of greater significance for me than the content.”

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://www.theguardian.com/

“Dreux’s Deer,”unknown date, by Alfred de Dreux (1810 – 1860), is the first painting featured in this novel about the dramatic effects of a painting with which a viewer connects on all levels. https://commons.wikimedia.org

“Lightning at Sea,” by Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), establishes a style of realism which aims at saturating the senses. Here the speaker connects the saturation of the senses with the life of her cousin, whom she believes to be mad. https://ro.m.wikipedia.org/

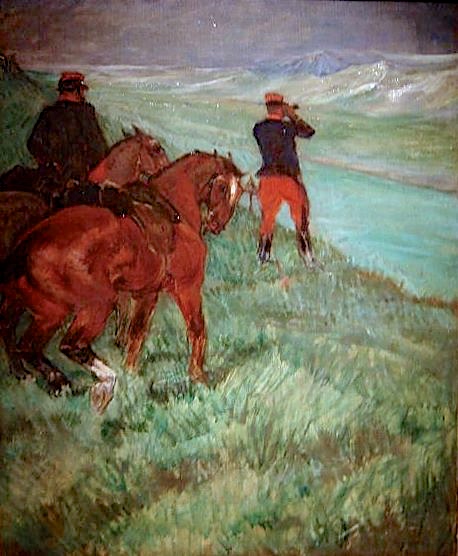

Toulouse Lautrec’s “En Observation,” 1901: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

Henri Rousseau’s “The Dream,” 1910. https://en.wikipedia.org/