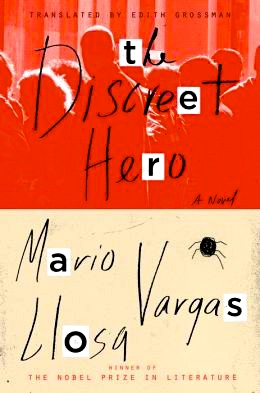

Note: Mario Vargas Llosa is WINNER of the Miguel de Cervantes Prize in 1994, WINNER of the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize in 2004, and WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2010.

“The earth is round, not square. Accept it and don’t try to straighten out the crooked world we live in. The gang [of extortionists] is very powerful, it’s infiltrated everywhere, beginning with the government and the judges. You’re really naïve to trust the police. It wouldn’t surprise me if the cops were in on it. Don’t you know what country we’re living in, compadre?”—Colorado Vignolo, to his friend, Felicito Yanaque.

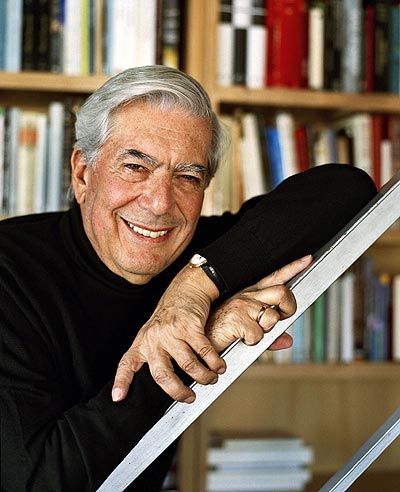

In his most recent novel, Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa returns to a simpler narrative style and plot scheme from what he used in his previous, more complex biographical novel, The Dream of the Celt, the story of Irish revolutionary Roger Casement, set in the Congo, the Peruvian Amazon, and Ireland in 1916. In The Discreet Hero, by contrast, the author writes for the sake of the story itself and the lessons it provides – an old-fashioned story in that we read it to find out what happens to Peruvian characters with whom we can identify as they act like ordinary people solving problems which reflect the reality of their Peruvian settings – in this case, Piura, a village in the northwest corner of Peru, and Lima, Peru’s capital and major city. The “story” here is actually two parallel narratives, running in alternating chapters and involving two characters, each of whom tries to be “discreet.” In the first plot, Felicito Yanaque, the owner of the Narihuala Transport Company, manages fleets of buses and trucks which operate throughout Piura, a village near the Pacific Ocean in the northwest corner of Peru. Felicito, fifty-five, takes great pride in his work, always remembering his father’s dying words: “Never let anybody walk all over you, son. This advice is the only inheritance you’ll have.” When he leaves for the office on this most important day, however, he finds, attached to his door, a letter demanding $500 a month for protection against “being ravaged and vandalized by resentful, envious people and other undesirable types.” He must, of course, be discreet about the message.

In his most recent novel, Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa returns to a simpler narrative style and plot scheme from what he used in his previous, more complex biographical novel, The Dream of the Celt, the story of Irish revolutionary Roger Casement, set in the Congo, the Peruvian Amazon, and Ireland in 1916. In The Discreet Hero, by contrast, the author writes for the sake of the story itself and the lessons it provides – an old-fashioned story in that we read it to find out what happens to Peruvian characters with whom we can identify as they act like ordinary people solving problems which reflect the reality of their Peruvian settings – in this case, Piura, a village in the northwest corner of Peru, and Lima, Peru’s capital and major city. The “story” here is actually two parallel narratives, running in alternating chapters and involving two characters, each of whom tries to be “discreet.” In the first plot, Felicito Yanaque, the owner of the Narihuala Transport Company, manages fleets of buses and trucks which operate throughout Piura, a village near the Pacific Ocean in the northwest corner of Peru. Felicito, fifty-five, takes great pride in his work, always remembering his father’s dying words: “Never let anybody walk all over you, son. This advice is the only inheritance you’ll have.” When he leaves for the office on this most important day, however, he finds, attached to his door, a letter demanding $500 a month for protection against “being ravaged and vandalized by resentful, envious people and other undesirable types.” He must, of course, be discreet about the message.

At the same time, in Lima, Don Ismael Carrera, the owner of an insurance company, is meeting with Rigoberto, his assistant, who wants to retire three years ahead of schedule. Ismael has a particular reason to want to delay Rigoberto’s retirement. His two sons, twins, have not inherited the abilities of their father or grandfather and have lived lives of complete dissolution, involving car crashes, rape, debts in Ismael’s name, forged receipts, and even the emptying of the petty cash box. Ismael has paid off the sons and now plans to disinherit them. The person who will inherit everything will be the woman Ismael unexpectedly plans to marry, at the age of almost eighty. The bride is thirty-eight years younger. Rigoberto will be a key to making all this possible, as Ismael needs a witness to the marriage after which he plans to take a long honeymoon to an unknown destination, and have Rigoberto manage the company and his sons – the hyenas – when they discover what their father has done. He, too, must, of course, be discreet.

Vargas Llosa, author of seventeen novels and now approaching age eighty himself, is clearly having great fun as he develops these two story lines, and at times the stories alternate happily between farce and soap opera as complications arise, and unexpected twists and turns send one or both of the plots careening. Eventually, coincidences bring the two plot lines together. Though the emphasis is on plot, almost exclusively, the author does bring in issues of marriage, the “comfort” of affairs outside of marriage, and occasionally even love. He spends significant time illustrating issues of parents and children – from Ismael’s “hyena” sons, to Felicito’s questions regarding whether one of “his” sons is really his, and to issues yet another character, Rigoberto, has with his son Fonchito, who is very bright – and maybe perfect. Fonchito, however, is conversing regularly with a “devil” whom no one else can see. The moral complexities of living in a culture in which bribery and extortion are common practice add to the difficulties of survival, and the reappearance of Sgt. Lituma (from Death in the Andes [1993] and Who Killed Palomino Molero [1986]), and Captain Silva (from Who Killed Palomino Molero) adds to the fun for fans of Vargas Llosa’s work. For those who understand Spanish, the discovery that the regional police chief is referred to as Colonel Rascachucha says it all. (This name is translated within the novel, but I won’t spoil the fun by telling here.)

Class differences also play a strong role in this plot. Mabel, Felicito’s lady love, who has been set up in her own place, is pointedly described as “not a whore,” but a “call girl,” with her own house and certain privileged clients. When Ismael decides to marry someone “below” him, not only is the world surprised, but so, too, is the prospective bride. In the other plot, Felicito has done the “honorable” thing as a young man by marrying his seventeen-year-old girlfriend who tells him that she is pregnant, but a few years later, he has “found love” elsewhere, while remaining married; his wife tolerates the arrangement. Ismael’s twin sons have managed to stay out of the newspaper only because the family has paid off reporters, and no one outside the family knows that one of them has run over a pedestrian in Miami, then fled to Lima while out on bail, something that a less wealthy son would have been unable to do.

Felicito’s decisions to challenge the extortionists make him a hero in Piura, but when he must deal with a bombing and a kidnapping, the complications raised by the extortionists are compounded. His “exemplary” behavior, however, does provide him with an acceptance into the Club Grau, a group he’d given up on joining because he “wasn’t white.” Vargas Llosa develops all the complications – then, unexpectedly and coincidentally, combines the two plot lines, bringing Piura and Lima together and happily resolving the problems. The last scene, in which Rigoberto, his wife, and his son take off for a European vacation provides the final resolution and the final laugh in this novel written for the pure pleasure of writing it, an entertainment on all levels for a reader looking for pure enjoyment, a rare commodity these days.

Also by Vargas Llosa: THE BAD GIRL, DEATH IN THE ANDES, THE DREAM OF THE CELT, THE FEAST OF THE GOAT

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://portal.uc3m.es/

Piura, a photo by Edgar Peru, is found here: http://www.panoramio.com/

Lima, on the Pacific Coast, is shown here: http://www.itascacg.com/

The map of Peru appears on http://www.infoplease.com/ Double click to enlarge.