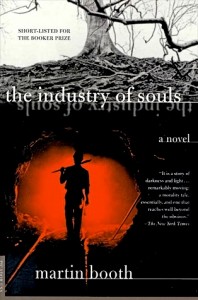

This morning, I was exchanging notes with a prolific reader who is also a friend of Mary Whipple Reviews, and she mentioned that one of her favorite books is The Industry of Souls by British author Martin Booth. I’d read and reviewed the book on Amazon in 2001, before I had this website, but I never reposted the review of that book here, despite the fact that when I read the book, I’d found it fascinating – and can even remember the book’s conclusion and the themes. The book was on the shortlist for the Booker Prize in 1998 and was selected as a New York Times Notable Book in 1999, but it never achieved the audience in the US that it deserves, despite its enthusiastic reviews.

This morning, I was exchanging notes with a prolific reader who is also a friend of Mary Whipple Reviews, and she mentioned that one of her favorite books is The Industry of Souls by British author Martin Booth. I’d read and reviewed the book on Amazon in 2001, before I had this website, but I never reposted the review of that book here, despite the fact that when I read the book, I’d found it fascinating – and can even remember the book’s conclusion and the themes. The book was on the shortlist for the Booker Prize in 1998 and was selected as a New York Times Notable Book in 1999, but it never achieved the audience in the US that it deserves, despite its enthusiastic reviews.

Martin Booth, the author of seventy works, including novels, collections of his own poetry, and volumes by other authors for which he was editor and publisher, passed away on Feb. 12, 2004, at the age of fifty-nine. This is the tenth anniversary of his death, and I hope that many of the people who read this review will honor his memory by exploring his work, maybe for the first time. (This book is readily available as an e-book and on used book sites.)

The Industry of Souls, written in 1998, opens with a thoughtful and loving tribute to the human spirit: “It is the industry of the soul to love and to hate; to seek after the beautiful and to recognise the ugly; to honour friends and wreak vengeance upon enemies; yet, above all, it is the work of the soul to prove it can be steadfast in these matters.” Here, and throughout the novel, author Martin Booth focuses on ideas of industry and work, but as he expresses his ideas, he often uses deliberate, poetic parallels to Biblical verses: “[There is] a time to love and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace [Ecclesiastes]…”

Alexander Bayliss, known as Shurik, is celebrating his eightieth birthday, as the novel opens. Walking around Myshkino, the Russian village where he lives, he visits with residents and recalls his life as a prisoner in the mines of Siberia, contrasting it with his life in Myshkino since then. At eighty, he is a man completely at peace with his world, celebrating the love, endurance, and forgiveness which have made his life not only bearable, but ultimately, full of joy. Through flashbacks and shifting time frames, he shows how he came to be a prisoner. Doing business in the Soviet Union, the forty-year-old British citizen was summarily arrested for espionage and sentenced to hard labor in the gulag, where he spent the next twenty years in a coal mine. Tortured and imprisoned in the mine, Bayliss has already seen the worst of mankind, but once he has reached “the lower depths,” the deepest part of the mine, where he will live for the next twenty years, the unit leader Kirill offers advice to the group, a similar but less poetic and more practical, message than that of Ecclesiastes: “Welcome to the rest of  your lives. And take a word of advice. Do not dream of the day of your release…Men go mad thinking about the past, the future. Here there is no then and no next. There is only now.”

your lives. And take a word of advice. Do not dream of the day of your release…Men go mad thinking about the past, the future. Here there is no then and no next. There is only now.”

In the hellish darkness and depths of the mine, however, Shurik ironically finds enlightenment. One of seven men in his labor group, he and his companions become a family, fiercely loyal to each other, accepting life moment by moment, with no thoughts wasted on a future they cannot afford to contemplate. The men come from varied backgrounds, and their views of life, molded by their own experiences, are all shared and often change during their time in the mine. When his long sentence finally expires, Shurik goes on to lead a quiet life in the small Russian village of Myshkino, the village where Kirill lived. Bayliss/Shurik has now lived there for the twenty years since he was released from the mines at age sixty.

A well preserved wooly mammoth baby, from 40,000 years ago. Photo by Francis Latreille/National Geographic

As he tells the stories which have made him who he is, the symbolism is clear and easily understood – the miners discovering a completely preserved wooly mammoth, then roasting and eating part of it; a story about a fox in a cage; Shurik, after his release, acting as teacher to the children of the village and sometimes speaking in aphorisms or proverbs; the making of bread in the village; Shurik arguing for the historic preservation of the local church, etc. Shurik/Bayliss has a new crisis to face on his eightieth birthday, however. Communism has failed and the Soviet Union has now dissolved, and a cousin in England has found him. The cousin will be arriving to see him soon, and he must decide whether to return to England or to stay.

This ambitious novel entertains at the same time that it conveys a strong message about man’s resilient spirit and the courage to forgive and endure. The language is simple, the images are unforgettable, the prose style is both musical and urgent, and the characters are admirable and sympathetic. A memorable and thoughtfully constructed novel in which every detail advances Bayliss’s message – and a wonderful introduction to Martin Booth for those who have never explored his work.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.doyletics.com/

The Siberian coal mine is shown on http://www.examiner.com/

The frozen baby mammoth from 40,000 years ago was photographed by Francis Latreille/National Geographic and appears on http://www.theguardian.com as part of a story on its discovery.