Note: This novel was WINNER of the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best Book in Canada in 2009, and WINNER of the Canadian Authors Association Literary Award for Fiction in the same year.

“ ‘Now the once,’ she said. It was the oddest expression he’d learned on the shore. Now the once. The present twined with the past to mean soon, a bit later, some unspecified point in the future. As if it was all the same, finally, as if time was a single moment endlessly circling on itself.”

With a poet’ s sensitivity to words and images, and a ballad-singer’s awareness of cadences and narrative tension, Michael Crummey creates a rich novel of Newfoundland from the nineteenth century through World War I. Deftly combining the brutal realities of subsistence fishermen with the mythic tales that give hope to their lives, he traces the lives of two families through six generations in Paradise Deep and the Gut, rural areas worlds away from life in St. John’s. With its huge scope in time and its limited scope in location, the novel honors the characters’ resilience as they struggle to survive during times of extreme privation (and six months of nearly paralyzing winter), while it also celebrates the stories and long-held myths which give interest and even hope to their lives.

s sensitivity to words and images, and a ballad-singer’s awareness of cadences and narrative tension, Michael Crummey creates a rich novel of Newfoundland from the nineteenth century through World War I. Deftly combining the brutal realities of subsistence fishermen with the mythic tales that give hope to their lives, he traces the lives of two families through six generations in Paradise Deep and the Gut, rural areas worlds away from life in St. John’s. With its huge scope in time and its limited scope in location, the novel honors the characters’ resilience as they struggle to survive during times of extreme privation (and six months of nearly paralyzing winter), while it also celebrates the stories and long-held myths which give interest and even hope to their lives.

When the novel opens in the middle of a long winter, the population is close to starving and all have gathered along the shore where a beached whale is expiring. “They weren’t whalers and no one knew how to go about killing the Leviathan, but there was something in the humpback’s unexpected offering that prevented the starving men from hacking away while the fish still breathed. As if that would be a desecration of the gift.” When the animal finally dies, the work begins of rendering the oil and cutting up the meat, a job which takes a whole day.

When they finally cut open the stomach, however, “[a] head appeared…a human head, the hair bleached white.” Suddenly, “Froth bubbled from the mouth and the corpse began coughing,” scaring away all but Devine’s Widow, the respected (and feared) old lady of the community, and her granddaughter Mary Tryphena. Though he reeks of fish, a condition which continues for his entire life no matter how often he is washed, the albino, who is a mute, is given a shed to live in on the widow’s property. Named “Judah,” a combination of Jonah and Judas, the man is completely solitary, blamed at first for the poor fishing, then celebrated when he rows out with the men on a fishing trip and the luck for the entire fleet changes, with more squid caught than they can eat. The next week the cod return.

however, “[a] head appeared…a human head, the hair bleached white.” Suddenly, “Froth bubbled from the mouth and the corpse began coughing,” scaring away all but Devine’s Widow, the respected (and feared) old lady of the community, and her granddaughter Mary Tryphena. Though he reeks of fish, a condition which continues for his entire life no matter how often he is washed, the albino, who is a mute, is given a shed to live in on the widow’s property. Named “Judah,” a combination of Jonah and Judas, the man is completely solitary, blamed at first for the poor fishing, then celebrated when he rows out with the men on a fishing trip and the luck for the entire fleet changes, with more squid caught than they can eat. The next week the cod return.

Other stories also achieve immortality in community lore. When Mary Tryphena’s infant brother, born when the whale arrived on shore, looks as if he’s going to die, there is no doctor to treat him, and he is eventually taken to Kerrivan’s tree, brought as a sapling on a ship from Ireland. Passed through its branches, a treatment thought to cure illnesses, the baby lives (and is then nicknamed Lazarus), and the tree bears sweet apples that summer for the first time. Local fishermen believe in merwomen, and one man almost goes overboard to follow one. A traveling priest, Father Phelan, “operates outside the bounds of church and state,” showing up unexpectedly and “overindulging” in both alcohol and sex. Though he tells Bible stories to the community, these stories do not seem much different to the local folk from the stories they have developed from their own experience. Biblical names, some of them ironic, pervade the novel. Mary Tryphena, Absalom, Lazarus, and Abel exist alongside Ann Hope, Martha, and Virtue.

The lives of the interconnected Devine and Sellers families, usually enemies, show the changes in the community over the next generation or two. A new priest from the Church of England changes the “rules” of the community, and in a darkly humorous episode, a body is stolen and reburied several times between the Catholic and the Protestant graveyards. A Catholic “cathedral” built for Fr. Phelan, collapses, and later burns, and a new Protestant church is built. Prices for the fishermen’s catches fluctuate, and King-me Sellers, a local judge, merchant, and government representative, cheats them out of their profits and their land. The old myths get forgotten, and Judah’s reputation declines. By the mid-1870s, there is a new priest and an archbishop “with an air of enthusiastic fasting about him.” And still the poor remain poor, and often starving. This is a time of “extravagant misery and want.”

The lives of the interconnected Devine and Sellers families, usually enemies, show the changes in the community over the next generation or two. A new priest from the Church of England changes the “rules” of the community, and in a darkly humorous episode, a body is stolen and reburied several times between the Catholic and the Protestant graveyards. A Catholic “cathedral” built for Fr. Phelan, collapses, and later burns, and a new Protestant church is built. Prices for the fishermen’s catches fluctuate, and King-me Sellers, a local judge, merchant, and government representative, cheats them out of their profits and their land. The old myths get forgotten, and Judah’s reputation declines. By the mid-1870s, there is a new priest and an archbishop “with an air of enthusiastic fasting about him.” And still the poor remain poor, and often starving. This is a time of “extravagant misery and want.”

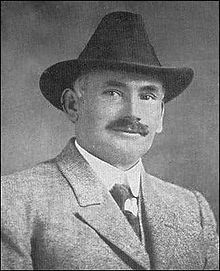

Part II takes place thirty y ears after that, as some of the original characters, now elderly, and their descendants, along with a new physician, Harold Newman, continue the themes and the family histories. Fishing is so depleted that the men now go to Labrador from May till September or October, leaving their families to fend for themselves for up to six months at a time. Politics becomes a fight between the Catholics and Protestants. The family of King-me Sellers, now led by Levi, continues to cheat the fishermen, and eventually a Fishermen’s Protective Union, led by William Coaker, is fought for and formed. The FPU is expected to change the face of politics and daily life by building wharves, warehouses, a school, a hotel, and offices on the waterfront. The passage of a law of conscription leads to the formation of a Newfoundland Regiment for World War I.

ears after that, as some of the original characters, now elderly, and their descendants, along with a new physician, Harold Newman, continue the themes and the family histories. Fishing is so depleted that the men now go to Labrador from May till September or October, leaving their families to fend for themselves for up to six months at a time. Politics becomes a fight between the Catholics and Protestants. The family of King-me Sellers, now led by Levi, continues to cheat the fishermen, and eventually a Fishermen’s Protective Union, led by William Coaker, is fought for and formed. The FPU is expected to change the face of politics and daily life by building wharves, warehouses, a school, a hotel, and offices on the waterfront. The passage of a law of conscription leads to the formation of a Newfoundland Regiment for World War I.

The individual stories of the two main families over six generations here are complex, and two helpful genealogies at the beginning of the book may become well-worn as the reader tries to keep the characters all straight. Though the book generally follows a chronological sequence, the individual stories move back and forth in time. It is common for the author to present a character in a certain set of circumstances, then to backtrack many years to show how those circumstances evolved, and, conversely, to hint at one outcome in one place and not develop the rest of the story for many pages. The conclusion ties up the loose ends and brings the reader out of the reality of World War I and back to the stories with which the novel begins. This study of the early fishing families of Newfoundland should appeal to those who enjoy family sagas, and the author’s study of the beliefs which make their lives meaningful and hopeful resonates through time.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.cbc.ca

The shallop boat depicted here, at twenty-eight feet long, is eight feet longer than the one used by Callum Devine and his men. Like Devine’s shallop boat, it has three sets of oars. Devine’s boat may or may not have had a sail. http://www.smithtrail.net

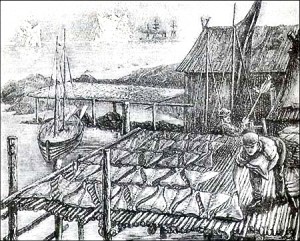

The drawing of the “fish flakes,” where cod was salted and dried, is from http://www.heritage.nf.ca

The photo of William F. Coaker, the founder of the Fishermen’s Protective Union, is from http://en.wikipedia.org.

The map of Newfoundland and Labrador is from http://www.worldatlas.com