“I longed for a way of life in which people made it a priority to look into each other’s eyes and communicate, soul-to-soul, uninterrupted, like in that Zulu warrior greeting we’d practiced in happiness class. I yearned for meandering conversations about all things important, all things banal. Bhutan, I imagined, might be as close as you could get on earth to what I’d been craving…”

When Lisa Napoli,  a journalist who has worked for public radio and CNN, attends a cookbook party in New York City, her friend Harris introduces her to a singularly attractive man. His handsome friend, Sebastian, is about to accompany him to Bhutan to do research for an article for Gourmet magazine. Napoli soon discovers through conversations with the two men that Bhutan is “the happiest place on earth” a place that is proud of its “Gross National Happiness Index.” In the midst of a midlife crisis herself, Napoli feels she has “been there, done that” for too long in the same job, adrift socially after the breakup of a long-term relationship. Now forty-three and childless, she reluctantly returns to her job at her home base in Los Angeles. Three weeks later, however, she receives an e-mail from the attractive Sebastian, asking her if she’d like to go to Bhutan to help with the start-up of a radio station, Kuzoo FM. With scarcely a second thought, she obtains a six-week leave of absence from her job and takes off for Bhutan, a Himalayan kingdom known as the Land of the Thunder Dragon.

a journalist who has worked for public radio and CNN, attends a cookbook party in New York City, her friend Harris introduces her to a singularly attractive man. His handsome friend, Sebastian, is about to accompany him to Bhutan to do research for an article for Gourmet magazine. Napoli soon discovers through conversations with the two men that Bhutan is “the happiest place on earth” a place that is proud of its “Gross National Happiness Index.” In the midst of a midlife crisis herself, Napoli feels she has “been there, done that” for too long in the same job, adrift socially after the breakup of a long-term relationship. Now forty-three and childless, she reluctantly returns to her job at her home base in Los Angeles. Three weeks later, however, she receives an e-mail from the attractive Sebastian, asking her if she’d like to go to Bhutan to help with the start-up of a radio station, Kuzoo FM. With scarcely a second thought, she obtains a six-week leave of absence from her job and takes off for Bhutan, a Himalayan kingdom known as the Land of the Thunder Dragon.

The book which results from this trip and the four additional trips that she takes between January, 2007, and the present, is as much a search for peace in her own life as it is a story about the happy world of Bhutan. The country, as she describes it, appears to be one in which time has stood still, the only purely Buddhist country in the world, with stringent rules about who may visit, and why, and about who may leave, and why. Ruled by a benevolent and much-loved king and his four queens (all sisters), the country has few telephones, fewer cars, no electricity in rural areas, and an “almost institutionalized resistance to conspicuous consumption.”

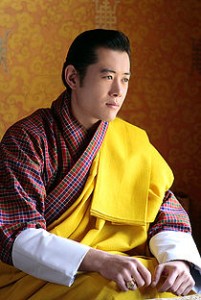

Shortly before the author arrives in the capital of Thimphu in January, 2007, however, she reads on-line that the fifty-year-old king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, who has been on the throne since 1972, has abdicated in favor of his son Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, aged twenty-six. The older king’s plan had always been to establish a constitutional monarchy, and during his own reign, he had continuously (and voluntarily) given up power to councils of advisors. This k ing, who was educated abroad in India and England, believed that by passing the rule on to his son, that the son would reign for a few years before democratic elections would be held and a true constitutional monarchy would be established. His son, educated at Andover and Cushing Academies in Massachusetts, at Wheaton College in Massachusetts, and eventually at Magdalen College, Oxford, and therefore well familiar with western life, is given the job of bringing the country into a more modern reality (with more TVs, radios, computers, the internet, etc.), while still preserving the values which make Bhutan the “happiest country on earth.”

ing, who was educated abroad in India and England, believed that by passing the rule on to his son, that the son would reign for a few years before democratic elections would be held and a true constitutional monarchy would be established. His son, educated at Andover and Cushing Academies in Massachusetts, at Wheaton College in Massachusetts, and eventually at Magdalen College, Oxford, and therefore well familiar with western life, is given the job of bringing the country into a more modern reality (with more TVs, radios, computers, the internet, etc.), while still preserving the values which make Bhutan the “happiest country on earth.”

Perhaps it was already too late to preserve these values when Lisa Napoli arrived. There she found that the people’s ideas of the United States (at least the people who lived in the capital and had access to TV) were based on what they saw on pop TV programs from the US. The people at her radio station were well familiar with Oprah and hoped that they could have a radio call-in show “like King Larry’s.” One of the young women at the station surfed the net for the Neiman Marcus Web site so she could see Burberry purses, and Sex and the City videos are watched avidly, readily purchased through India. Yet many people still wear traditional dress (at least on holidays), the Buddhist priests still are called upon to do blessings and pujas, a nd houses are decorated with paintings of ten-foot phalluses, the “logic” being that “When you have a phallus painted on the house, people will be too ashamed to look and to covet what they don’t have. In this way the phallus wards off evil spirits.”

nd houses are decorated with paintings of ten-foot phalluses, the “logic” being that “When you have a phallus painted on the house, people will be too ashamed to look and to covet what they don’t have. In this way the phallus wards off evil spirits.”

After giving straightforward “travel guide facts” about Bhutan, the author then confesses that she has fallen in love with the country. “Timing and circumstance collided to ignite this love affair. It didn’t hurt that I had a lifelong fascination with anyplace in the throes of evolution…In many ways Bhutan was a start-up…an ancient, once-secluded kingdom transitioning now at warp speed. A new king, a new democracy about to dawn, a new constitution.” With little pause and less anal ysis, however, she then states that “The twin cultural influences of technology and media were spreading rapidly, challenging and eroding Bhutan’s very foundation.” How and why this is happening so quickly in a culture which she has described as having firm foundations in deeply held core values remains an unanswered question, and whether this erosion can be stopped is not addressed.

ysis, however, she then states that “The twin cultural influences of technology and media were spreading rapidly, challenging and eroding Bhutan’s very foundation.” How and why this is happening so quickly in a culture which she has described as having firm foundations in deeply held core values remains an unanswered question, and whether this erosion can be stopped is not addressed.

Throughout the story, the author, ever the journalist, gives the facts and figures about the country and its people, and about how she adapts to life there, but she appears to be an observer, rather than a real participant in a rich culture on the verge of being lost. Ultimately she decides, after her five short visits, that she has found all she has needed in Bhutan for the time when she needed it. It is a bit of a letdown for the reader to realize that she has mined the experience as much as she intends to. The book offers thinly developed factual data about Bhutan, and a good deal of information about the author’s own personal crisis, but she seems ready now to put all that behind her and move on , “going for a walk outside in the California sunshine.” Ultimately, the reader is left full of questions about the “real” Bhutan, the real “happiness” of its people, and how well the country will adapt to the changes which seem about to envelop it.

, “going for a walk outside in the California sunshine.” Ultimately, the reader is left full of questions about the “real” Bhutan, the real “happiness” of its people, and how well the country will adapt to the changes which seem about to envelop it.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://marketplace.publicradio.org

The US- and Oxford-educated new king is now thirty-one years old. http://www.ask.com

Members of the Royal Family await the coronation of Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck in 2007. Perhaps his mother and the three other queens are the women on the right. All the participants are wearing traditional dress: http://www.dailymail.co.uk

The map of Bhutan is from http://kids.mapzones.com

The primary food of Bhutan, according to the author, is emadatse, made almost entirely of hot peppers. http://read-it-forward.crownpublishing.com

A YouTube trailer of Taking the Middle Path to Happiness may be seen here: