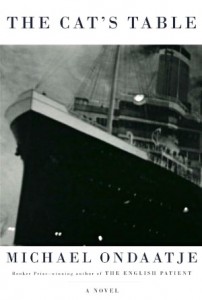

Note: Michael Ondaatje was WINNER of the Booker Prize (1992) for The English Patient.

“This journey was to be an innocent story within the small parameter of my youth, I once told someone. With just three or four children at its centre, on a voyage whose clear map and sure destination would suggest nothing to fear or unravel. For years I barely remembered it.”–Michael, the novel’s narrator

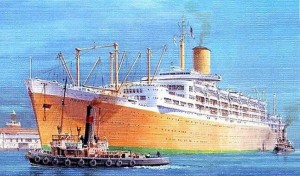

Setting his latest novel on the Oronsay, a passenger ship going between Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and London in 1954, Michael Ondaatje writes his most accessible, and, in many ways, most enjoyable novel ever. Having grown up in Ceylon, from which he himself was sent to England to be educated as a boy, the author certainly understands what it feels like to be a child on a ship for three weeks, like his main character here, though author Ondaatje says that all the characters in the book are fictional, including the main character. The novel has such a ring of truth and Ondaatje’s depiction of the characters is so true to the perceptions of an eleven-year-old traveling on his own, however, that it is difficult for a reader to remember that the boy in the book is imagined and not real. Since the boy grows up and becomes an author like Ondaatje, his adult conclusions as he looks back on the importance of these events and what they have meant in the grand scheme of his life become even more vivid.

Setting his latest novel on the Oronsay, a passenger ship going between Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and London in 1954, Michael Ondaatje writes his most accessible, and, in many ways, most enjoyable novel ever. Having grown up in Ceylon, from which he himself was sent to England to be educated as a boy, the author certainly understands what it feels like to be a child on a ship for three weeks, like his main character here, though author Ondaatje says that all the characters in the book are fictional, including the main character. The novel has such a ring of truth and Ondaatje’s depiction of the characters is so true to the perceptions of an eleven-year-old traveling on his own, however, that it is difficult for a reader to remember that the boy in the book is imagined and not real. Since the boy grows up and becomes an author like Ondaatje, his adult conclusions as he looks back on the importance of these events and what they have meant in the grand scheme of his life become even more vivid.

Main character Michael, eleven years old, has been living in Ceylon all his life, for the past three years in the care of his aunt and uncle. His parents have divorced, his father is no longer part of his life, and his mother returned to England several years ago. Suddenly, Michael finds himself being driven to the port where he is expected to get on a ship and travel alone for twenty-one days to London, where he will be greeted by the mother he has not seen for one-third of his life. He does not know if he will recognize her, but he shows no trepidation. He is on his own on the ship, and his adventuresome nature and his resourcefulness give him all the self-confidence he needs to regard this trip as an exciting alternative to the life he has known to date. Boarding the ship without a backward glance, he goes to his cabin on the lowest deck of the ship, yielding himself completely to the new opportunities that will surely unfold there.

In the dining room after departure, he sits at the “cat’s table,” the lowest-status table, quickly befriending two other children his own age, both also leaving for school in London. Cassius, a year ahead of him at his previous school and a notorious mischief-maker, and Ramadhin, a gentle soul who suffers from both asthma and heart problems, quickly become his inseparable companions. Also at the table are a variety of “exotic” adults representing an assortment of professions, none of them socially “noticeable” – among them a “ship dismantler” who salvages old ships, the manager of the ship’s kennel, a pianist who plays with the band, a young botanist, and a woman who is transporting twenty or thirty pigeons, some of which she carries close to her in a specially designed coat.

In the dining room after departure, he sits at the “cat’s table,” the lowest-status table, quickly befriending two other children his own age, both also leaving for school in London. Cassius, a year ahead of him at his previous school and a notorious mischief-maker, and Ramadhin, a gentle soul who suffers from both asthma and heart problems, quickly become his inseparable companions. Also at the table are a variety of “exotic” adults representing an assortment of professions, none of them socially “noticeable” – among them a “ship dismantler” who salvages old ships, the manager of the ship’s kennel, a pianist who plays with the band, a young botanist, and a woman who is transporting twenty or thirty pigeons, some of which she carries close to her in a specially designed coat.

On the journey, during which they survive storms and all manner of other unusual events, Michael and his friends learn about life by observing what happens around them, sometimes unwittingly creating events which have long-term consequences for others and becoming involved in mysteries they do not understand. They delight in using one of the lifeboats to overhear conversations and observe life at its most basic. As Michael notes, “What is interesting and important happens mostly in secret, in places where there is no power. Nothing much of lasting value ever happens at the head table, held together by a familiar rhetoric. Those who already have power continue to glide along the familiar rut they have made for themselves.” The boys stay up all night, use the first-class swimming pool early in the morning, and eat the first class food (hiding in lifeboats to eat it). They observe love affairs blooming, a man who is dying and who must get to London before it is too late, and a prisoner arrested for murder who is exercised on deck only late at night. “We came to understand [a] small and important thing – that our lives could be large with interesting strangers who would pass us without any personal involvement.”

The first half of the novel is a straightforward narrative, Ondaatje’s most uncomplicated narrative ever, as Michael and his friends explore the ship and learn from their experiences. At the midpoint of the novel, however, Michael, as narrator, begins to move forward and back in time, telling about his life years later in London, then moving backward as he remembers an event from 1954, which may have been a key learning experience only partially explicated in the narrative up to that point, then moving forward still further to the years when he is in his thirties, then backing up again to the events on the ship which foreshadowed his later life. The flashbacks and flashforwards feel completely natural, the product of memory, rather than artifice.

By the time he reaches his twenties, Michael is a successful novelist, and his travels throughout the world regarding his books have led him to reconnect with some of the people he knew years ago on the Oronsay. All is not sweetness and light, however. Some of the people he has known have vanished, at least one has died, and one has simply used life on the Oronsay as a starting point from which to move on, leaving the past behind. As Michael continues to be drawn into the past through his memories, his own ability to continue learning from the past, drawing on it, and profitting from it continues.

Ondaatje creates a delightful, often charming, picture of the life of young Michael during his three weeks aboard the Oronsay, but the novel’s thematic importance lies in his depiction of the long-term effects of childhood events on our later lives as we become privy to new information about these events, look at them from an adult’s perspective, and, perhaps, reevaluate our memories of them and our own roles in them. Filled with glorious descriptions and action-filled scenes of great emotional resonance, some of them shocking, this is arguably Ondaatje’s most naturally integrated novel. Ultimately, he concludes that “there is a story, always ahead of you. Barely existing. Only gradually do you attach yourself to it and feed it. You discover the carapace that will contain and test your character. You find in this way the past of your life.”

ALSO by Ondaatje: WARLIGHT

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.topnews.in

This painting of the Orient Line’s Oronsay, with its golden sides, parallels the description of the ship seen in the novel. www.ssmaritime.com

The first stop on the journey from Ceylon to England is in Aden, as the ship enters the Red Sea. This photo of Aden from 1960 appears on http://davidderrick.wordpress.com

Port Said, at the end of the Suez Canal, is another stop along the way. This night-time scene is from http://en.wikipedia.org

Late in the book Michael takes another trip by boat, on the Capilano, a ferry between Vancouver and Bowen Island: This photo by Gabor Retei appears on http://www.panoramio.com.