“A black and white feather began it. A magpie’s perhaps. We called the novices magpies: black habits and white veils. The nuns, in plain black: holy crows. Or holy hens. The young cure´, strutting plumply among us with pursed lips and folded arms, was Chanticleer…The nuns pecked and flapped for his attention.”

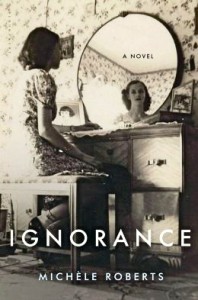

A fast-paced plot, a setting that is both horrific and familiar, a mixture of fantasy with traditional religion, and unusual characters dealing with pressing political, economic, and moral issues capture one’s attention from the opening pages, as author Michele Roberts keeps the reader moving swiftly through the French countryside from 1931 – 1945. Jeanne Nerin, the daughter of a widowed mother who works as a laundress and housekeeper, and Marie-Angele Baudry, the daughter in the family for whom Jeanne’s mother works, are the only two full-time boarders at a convent school, as the story opens. Nine years old, they are there because Jeanne’s mother has been hospitalized, leaving Jeanne without someone to care for her, and because Marie-Angele’s pregnant mother now has no one to do the laundry and heavy work in the Baudry household. Marie-Angele is quick to point out that Jeanne is at the convent as a “charity case” with other people paying for her fees, one of numerous such comments which do not endear her to Jeanne. In addition, Jeanne’s mother was Jewish before she converted to Christianity under the sponsorship of Mme. Baudry, who feels she is performing her Christian duty by hiring her for housework, an attitude not lost upon Mrs. Nerin and her daughter. Casual anti-Semitic remarks throughout the novel reflect the attitudes in France nearly ten years before the Germans arrive.

A fast-paced plot, a setting that is both horrific and familiar, a mixture of fantasy with traditional religion, and unusual characters dealing with pressing political, economic, and moral issues capture one’s attention from the opening pages, as author Michele Roberts keeps the reader moving swiftly through the French countryside from 1931 – 1945. Jeanne Nerin, the daughter of a widowed mother who works as a laundress and housekeeper, and Marie-Angele Baudry, the daughter in the family for whom Jeanne’s mother works, are the only two full-time boarders at a convent school, as the story opens. Nine years old, they are there because Jeanne’s mother has been hospitalized, leaving Jeanne without someone to care for her, and because Marie-Angele’s pregnant mother now has no one to do the laundry and heavy work in the Baudry household. Marie-Angele is quick to point out that Jeanne is at the convent as a “charity case” with other people paying for her fees, one of numerous such comments which do not endear her to Jeanne. In addition, Jeanne’s mother was Jewish before she converted to Christianity under the sponsorship of Mme. Baudry, who feels she is performing her Christian duty by hiring her for housework, an attitude not lost upon Mrs. Nerin and her daughter. Casual anti-Semitic remarks throughout the novel reflect the attitudes in France nearly ten years before the Germans arrive.

In many ways the two girls represent the dichotomies of their times. Jeanne will do whatever is necessary to survive, including stealing food from the convent, and later taking jobs which demean her. Marie-Angele and her family, for all their religiosity, consider themselves superior because they are wealthier, and these hypocritical attitudes are also reflected, ironically, in the attitudes Jeanne experiences with the nuns in the convent, who require much more in the way of physical chores from her than they do from Marie-Angele. When Jeanne and Marie-Angele, unsupervised one weekend afternoon, daringly climb over a wall from the convent to the house next door, they find themselves confronted by a hermit they have always referred to as Bluebeard, and they react very differently to the experience. Jeanne is fascinated by this man, Mr. Jacquotet, a widowed artist who has painted the walls of his rooms many beautiful colors, has drawn studies of nude women, and has painted stacks of wild, expressionistic paintings. Marie-Angele, in a strange episode of precocious sexuality, is far more interested in assuming the erotic poses she sees in some of his drawings and which she wants him to draw for her, as if she is daring him to touch her.

Watercolor, Magpie Feather, the opening image in the novel, by Sarah of Tendril Studio, Australia

When the girls leave and find the doors to the convent locked, Marie-Angele blames everything on Jeanne. In typical fashion, all the adults, both at the convent and in their homes, make Jeanne and Marie-Angele promise not to say or do anything about this episode, apparently not wanting to stir up trouble or cast aspersions on Marie-Angele – more hypocrisy, which becomes the major theme throughout.

Though Jeanne is the primary narrator, Marie-Angele also serves as a narrator, expressing her own versions of events and her own attitudes toward life, and the two reflect the very different realities of France during this period. Because time is not linear in this novel, the author is able to paint a picture of life from several different vantage points, not just in point of view but also in time. In the first chapter, for example, Jeanne begins the story at age nine. In the second, Marie-Angele, now twenty, shares her life as she is being courted. In successive chapters told from their own points of view, Jeanne is thirteen, then a flashforward to Marie-Angele, who is married with seven children, then a flashback to Jeanne at eighteen. Two additional chapters bring the story up to the conclusion of the war.

Germans move through a small French village.

Gradually, the author creates a broad but intimate picture of life for these French women before, during, and after the war. Whether because of economic hardship or because of the mores of the day, which also reflect the attitudes of the church, they have few choices in their lives, and Jeanne, in particular, must do the best she can with what she has. Love must sometimes be sacrificed for survival, and sometimes there are simply no good choices. For Jeanne, however, honesty is always the rule, no matter how she may have to pay for it; for Marie-Angele, honesty is not necessary. She can always twist events to her own advantage and hide her complicity. Again, the theme of honesty competes with hypocrisy, not just in the lives of these two women but in a broader sense.

Women of the Night by Edgar Degas, in a style similar to that of M. Jacquotet

One of the most revelatory characters in the novel is Maurice Blanchard, a man who works in the local government but who straddles the line ethically. A man who knows all the characters featured here, Maurice is for sale. When the Germans finally arrive, he provides exit papers and passports for some of the Jews and others who need to leave the country, but he charges exorbitant fees and lines his own pockets. He is dishonest with his wife about his associations with other women, especially those at the local “dance hall,” but he feigns righteousness. He associates with both the Germans and the Jews, and he does what he believes he has to do, strictly for his own benefit.

The plot of this novel unwinds obliquely, but the events themselves are presented in simple terms, and the story itself is not complex. What makes this novel so different from other novels which focus on the same time period, however, is the lush, sensuous language. Roberts writes like an artist (which is how Jeanne sees the world), with a reliance on sense impressions and unusual and lively metaphors to bring to life what could otherwise be a depressing story. The madam of a house of ill repute is described as “aging meat, marbled with fat, giving off a whiff of corruption.” Jeanne’s mother, “in her black dress looked lean as a vanilla pod.” As for war, it “fell out of the sky.” Dozens more such images pervade the novel. Sure to become a popular success not just for its story but for its style, this novel will surely appeal to a wide audience.

Camden Town, England, a refuge for some French citizens during the war.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.thetimes.co.uk

Signed prints of this watercolor of the Magpie feather, the image which opens the novel, are available from the artist, here: http://www.etsy.com

The German march through France, 1940, may be found on http://pictureshistory.blogspot.com

The Degas drawing from a brothel are from: http://farm6.static.flickr.com

Camden Town, a refuge far from France for some Jews, is seen here: http://www.tangology.org

ARC: Bloomsbury