Note: Mo Yan was WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2012. In 2011, this novel, Frog, was WINNER of the prestigious Mao Dun Literary Prize, awarded every four years by the Chinese Writers Association. Mo Yan’s novel Big Breasts and Wide Hips was WINNER of the Man Asian Literary Prize in 2007.

“One gazes upon China’s Great Wall or the Egyptian pyramids without a thought to the blanched bones buried beneath these magnificent edifices. Over the past two decades, China has resolved the problem of its population explosion by draconian measures, not only for the sake of the country’s development, but as a contribution to humanity…We [all] live together on this tiny planet, with its finite resources.”—Tadpole, the novel’s speaker.

When Chinese author Mo Yan won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2012, controversy swirled. Mo has been able to publish his works in China because he works within the existing communist system and is considered part of the establishment in China, while other talented but less discreet Chinese writers are prohibited from publishing without serious censorship, and in some cases feel they must leave China in order to write from the heart. Famed writer Ha Jin, for example, was an exchange student at Brandeis University when the devastating Tiananmen Square uprising took place in 1989, and he chose to emigrate and stay in the United States at that point. In extreme cases, such as that of writer Liu Xiaobao, who in 2009 was tried and convicted in China for “inciting subversion of state power,” writers have been jailed – in Liu’s case for eleven years. Liu had challenged the regime directly as one of the authors of the “Charter 08 Manifesto” for human rights. Mo, on the other hand, has always lived a quieter, less attention-seeking life. His focus on the small communities in which he has lived allows him to create “small fry” characters with all their quirks and peculiarities, and through them to depict everyday life and provide rare insights for non-Chinese readers. His unusual perspective adds up to grand ideas for the reader, even within the “establishment.”

When Chinese author Mo Yan won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2012, controversy swirled. Mo has been able to publish his works in China because he works within the existing communist system and is considered part of the establishment in China, while other talented but less discreet Chinese writers are prohibited from publishing without serious censorship, and in some cases feel they must leave China in order to write from the heart. Famed writer Ha Jin, for example, was an exchange student at Brandeis University when the devastating Tiananmen Square uprising took place in 1989, and he chose to emigrate and stay in the United States at that point. In extreme cases, such as that of writer Liu Xiaobao, who in 2009 was tried and convicted in China for “inciting subversion of state power,” writers have been jailed – in Liu’s case for eleven years. Liu had challenged the regime directly as one of the authors of the “Charter 08 Manifesto” for human rights. Mo, on the other hand, has always lived a quieter, less attention-seeking life. His focus on the small communities in which he has lived allows him to create “small fry” characters with all their quirks and peculiarities, and through them to depict everyday life and provide rare insights for non-Chinese readers. His unusual perspective adds up to grand ideas for the reader, even within the “establishment.”

In this novel, Mo’s speaker is Tadpole, also known as Wan Zu or Xiaopao, who writes letters to his Japanese teacher, Sugitani Akihito, from 2002 to 2009. Sugitani has taught a writing class to Tadpole and others in Beijing, and on one occasion, Tadpole takes him to meet his Aunt Gugu, a woman who has worked as a rural obstetrician for more than fifty years. Gugu, a fearless woman who has seen and done it all – before, during and after China’s “one-child” policy – serves as a model for Sugitani’s writing class when he suggests that the class write about her. One student decides to write a novel about Gugu’s life, and Tadpole decides to write a play. As he works on his writing project and reports to the sensei over the next few years, Tadpole recreates all aspects of Gugu’s personal and professional life, beginning in 1960 and continuing to the present. He vividly reconstructs several historical periods, from the famine of the late 1950s through the country’s efforts at population control, stressing the emotional effects of these policies, not just on the poor population but on medical personnel themselves. The immediacy and honesty of Tadpole’s writing to his teacher, and the powerful personality of Gugu herself combine to expand the issues of population control from the small community in Gaomi County, where they all live, to the population at large. The world “writ small” inevitably becomes the world “writ large.”

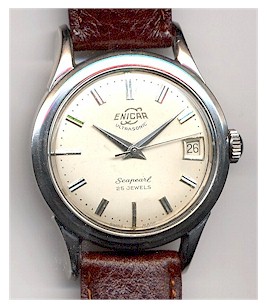

Gugu’s Enicar watch from Switzerland was the most exotic thing any of the children of Gaomi had ever seen, a present from her fiance in 1955.

Including side bars throughout, in which he talks about such topics as the choices of names (in Tadpole’s community, many personal names are the names of body parts, like Gallbladder and Cheek) and branching out into traditional stories, and occasional tales of animals and legends, the author first introduces the subject of famine in 1960, through the casually told and “amusing” story of the children eating pieces of coal and exclaiming over how tasty it is. Gugu, Tadpole’s aunt, is working in obstetrics during this period, and by 1961, she notes that “over a two-year period…not a single infant was born in any of the more than forty villages that made up the People’s commune.” The reason was not any government policy. It was, instead, a result of the famine. Even in the midst of famine, however, life somehow goes on, and for Tadpole, Gugu’s reputation at this time is symbolized not by her dedication, but by the relatively simple Swiss Enicar wristwatch that she wears, an “exotic” gift unlike anything anyone in town has ever seen before, given by her fiancé, an air force pilot.

A scene in Gaomi, where the novel takes place. Harvested corn, the current leading crop, has apparently replaced the sweet potatoes of this novel.

In 1962, an unexpectedly large sweet potato harvest changes lives, and people begin referring to the “sweet potato babies.” Almost three thousand babies are born that year in fifty-two villages. Gugu and her fellow physician (and nemesis) Huang together deliver eight hundred-eighty babies in five months. Alarmed by the difficulty of feeding this burgeoning population, the government begins suggesting that people limit families to just two babies. Soon control becomes more stringent. Gugu begins advocating family planning, birth control, and eventually vasectomies. Still later, abortion becomes not only an option but eventually a requirement for many. The emotional effects of often late-term abortions on families is horrifying, as the reader sees through Tadpole, his wife, and his contemporaries in the community. And while maternal deaths as a result of late-term abortions cause untold agony, barren couples also experience a sense of loss and begin to resort to using surrogates, made possible through the connivance of low level party members engaged in a variety of illegal “private” enterprises.

Oriole (female) in peach orchard, an image which takes on symbolic meaning forTadpole when he visits the graves of his mother and deceased wife on the eve of his remarriage. Photo by Lynda Goff.

The author varies his styles throughout this broad picture of late twentieth century

China. When one character tries to get his father to have a vasectomy, the action devolves into slapstick comedy featuring a saber, a pigpen, and a chase. Another scene, totally different, in which a character is about to remarry, is emotionally moving and symbolic: The widower on the day of his remarriage visits his mother’s grave and that of his deceased wife and sees a whirlwind. “At that moment an oriole in a peach tree released a long cheerless call that nearly tore my insides apart.” He quietly leaves ripened peaches on the graves, making promises to his deceased family. Ultimately, Tadpole’s play, called Frog, is reproduced within the novel, adding a touch of magical realism and fantasy to the ending of the novel. Many themes related to reproduction and contraception, and many different literary styles highlight the individualized characters here, as Mo Yan takes on fifty years of history and a wide variety of characters to bring rural China alive in ways completely unfamiliar to most western audiences.

ALSO by Mo Yan: BIG BREASTS AND WIDE HIPS and SHIFU, YOU’LL DO ANYTHING FOR A LAUGH

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Ed Jones of AFP, Getty Images appears on http://www.theguardian.com

The Enicar Swiss watch was the most exotic possession any of the children in Gaomi had ever seen when Gugu began wearing it in 1955. http://www.cjbalm.com/

Gaomi, where author Mo Yan grew up, now grows corn as its main crop, replacing the sweet potatoes which were the biggest crop in 1962. http://www.avaxnews.net

A symbolic scene takes place when Tadpole sees an oriole in a peach orchard when he goes to the cemetery to pay his respects to his mother and his first wife. Photo by Lynda Goff: http://lyndagoff.com/taxonomies/orchard-oriole/ Many other wonderful bird photos appear on this site.

The photo of Mo’s father, in front of Mo’s childhood house, appears on http://www.theguardian.com/

ARC: Viking Press