Note: Mo Yan was WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2012.

“Not a single thing in this world is eternal. Take this famous garden, for instance. Two hundred years ago, when the Qing emperor built it, no one could have imagined that in the short space of two centuries it would be reduced to ruins…The marble stones in the vast halls on which the emperor and his ladies took their pleasure [back then]…may now be the rocks on which commoners have built a pigsty.”—Speaker in “Shen Garden,” referring to the Yuanming Gardens in Beijing.

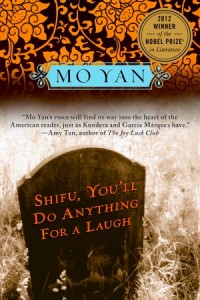

This strange and sometimes eerie collection of short stories by Nobel Prize winner Mo Yan is guaranteed to stick in the minds of its readers, not just because it is wonderfully written by a man whose country is not as open to foreigners as this book is, but because its reality is so far removed from what any of us have experienced or even imagined. Seven short stories and one novella create a sometimes mystical or mysterious mood, oftentimes more akin to horror than to fantasy, a mood that is guaranteed to make readers sit up and take notice, even as they may be lulled by the “folky” and confidential attitude of several speakers as they reflect on their lives. Whether one should interpret some of the events described in this collection as dark humor, shocking dramatic irony, or simply as the reality of the various Chinese speakers and, one presumes, the author, is a question which readers will have to explore on their own. Though author Amy Tan, in a blurb on the book’s cover, suggests that “Mo Yan’s voice will find its way into the heart of the American reader, just as Kundera and Garcia Marquez have,” I suspect that many readers will react as I did – my heart was, in fact, aching, often shocked, and sometimes appalled at what passes for normal life in rural China. The residual feeling of this collection, at least for me, is not that of folk tales or fantasy, in which one can smile, amused, at the flights of imagination, but of the sometimes terrible realities which underlie these stories.

This strange and sometimes eerie collection of short stories by Nobel Prize winner Mo Yan is guaranteed to stick in the minds of its readers, not just because it is wonderfully written by a man whose country is not as open to foreigners as this book is, but because its reality is so far removed from what any of us have experienced or even imagined. Seven short stories and one novella create a sometimes mystical or mysterious mood, oftentimes more akin to horror than to fantasy, a mood that is guaranteed to make readers sit up and take notice, even as they may be lulled by the “folky” and confidential attitude of several speakers as they reflect on their lives. Whether one should interpret some of the events described in this collection as dark humor, shocking dramatic irony, or simply as the reality of the various Chinese speakers and, one presumes, the author, is a question which readers will have to explore on their own. Though author Amy Tan, in a blurb on the book’s cover, suggests that “Mo Yan’s voice will find its way into the heart of the American reader, just as Kundera and Garcia Marquez have,” I suspect that many readers will react as I did – my heart was, in fact, aching, often shocked, and sometimes appalled at what passes for normal life in rural China. The residual feeling of this collection, at least for me, is not that of folk tales or fantasy, in which one can smile, amused, at the flights of imagination, but of the sometimes terrible realities which underlie these stories.

Using Northeast Gaomi Township as his setting (the fictionalized name for Dalan Township where the author lives), Mo Yan creates fast-paced narratives, describing events so specifically that even a foreigner will understand both the action and the behavior of the main characters. Nature often plays a strong part in the descriptions, suggesting that what happens to the characters is equivalent to what happens in a nature that is represented primarily by “tooth and claw.” In almost every story, the main character, no matter how honorable, is foiled by outside forces, and sometimes by nature – always a victim with little or no control over his life and destiny.

The stories begin with a seemingly light-hearted novella, “Shifu, You’ll Do Anything for a Laugh,” and become progressively more intense for the non-Chinese reader until the final story, “Abandoned Child,” explodes with its revelations of continuing horror. In the former, a good worker who has done everything right for his entire working life and has received many commendations, is suddenly terminated, along with almost everyone else at the factory where he works, and he must find a new source of income. The worker’s life is irrelevant: he is nameless and faceless. Looking for a way to earn money, he finds an abandoned school bus in the woods n ear the reservoir, rehabilitating it as a place for couples to have trysts, and painting it in camouflage paint. He rents it by the hour, with discounts for repeat visitors. When one tryst appears to go terribly wrong, he fears retribution and decides to confess to the authorities, with surprising and darkly comic results.

ear the reservoir, rehabilitating it as a place for couples to have trysts, and painting it in camouflage paint. He rents it by the hour, with discounts for repeat visitors. When one tryst appears to go terribly wrong, he fears retribution and decides to confess to the authorities, with surprising and darkly comic results.

“Abandoned Child,” by contrast, is a shocking story told by a writer (of what appears to be purple prose, judging from his introduction to this story) who finds a note on a tree in the rural countryside, urging the finder to look immediately to the fields to save a human life. In a field of bright sunflowers, the writer finds an abandoned baby only a few hours old. The baby, of course, is a girl. What follows is the initial effect on the writer’s family, which has honored the One Child law, though they have longed for a son. When the writer takes the baby to authorities, the full horror of what life has in store for this abandoned baby is revealed, along with the long-term effects on this writer and his family and ultimately the country.

In between these two stories are six others which reveal much about Chinese life. In “Man and Beast,” a Chinese soldier is captured and conscripted by the invading Japanese, sent to work in Hokkaido during the early days of World War II. The conscript has witnessed atrocities committed by the Japanese against his daughter, has seen his troops slaughtered, and has watched the homes in his village burn. In a daring escape, he finds the cave of a fox in the mountains, where he lives, alone, for the next ten years. Told by the man’s grandson, the story describes someone who has become half man and half beast, and when, in a grand battle, the grandfather and a fox face off, the battle takes on symbolic overtones. “Soaring” tells of a woman who flies into a tree to escape her new husband, and the retribution taken against her by the police. “The Cure” shows that even when a man and his son, out of love for the man’s elderly mother, take terrible chances in order to find a cure for her approaching blindness, that their love can never be enough.

“Iron Child” is the strange and even terrifying story of a child forced to live in a “nursery” while his parents are conscripted to work building a nearby railroad. When the job is complete, no one comes to claim him. He connects with a fantastic “Iron Child,” one who eats iron because there is no food, another image with symbolic significance. The child’s fate, as in other stories, shows again that the individual has little or no importance. “Love Story” suggests that there is only sex, not love. And “Shen Garden,” which is told as a love story set in Beijing, illustrates the idea that “not a single thing in this world is eternal.”

“Iron Child” is the strange and even terrifying story of a child forced to live in a “nursery” while his parents are conscripted to work building a nearby railroad. When the job is complete, no one comes to claim him. He connects with a fantastic “Iron Child,” one who eats iron because there is no food, another image with symbolic significance. The child’s fate, as in other stories, shows again that the individual has little or no importance. “Love Story” suggests that there is only sex, not love. And “Shen Garden,” which is told as a love story set in Beijing, illustrates the idea that “not a single thing in this world is eternal.”

The stories are fascinating to read, and though the overall impression they leave is one of sadness at the emotional and psychological horrors which rural Chinese have had to endure and adapt to, one discovers that even in Beijing there is no guarantee of happiness. In fact, happiness does not even seem to be a goal among the characters here. The writing is clear and unequivocal, and western readers cannot help but sit up and take notice of the contrasts between our cultures, and of these characters’ power of sheer endurance in the face of hardship. Highly recommended.

Also by Mo Yan: BIG BREASTS AND WIDE HIPS and FROG

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.bbc.co.uk

The camouflaged bus, similar to what the speaker created, in “Shifu, You’d Do Anything for a Laugh,” is from

http://attractions.uptake.com

A fox’s cave on a cold mountain may be found here: http://arkansasstateparks.wordpress.com

The Yuanming Gardens of the Old Imperial Palace, destroyed by the British during the Second Opium War in 1860, are still visited in Beijing, though they are not restored. http://www.kinabaloo.com