“We will defer only to the brute force of guns. Maybe the answer lies in [Somalia’s] history since the days of colonialism, and later in those of the Dictator, and more recently during the presence of U.S. troops: these treacherous times have disabused us of our faith in uniformed authorities—which have proven to be redundant, corrupt, clannish, insensitive, and unjust.”

Returning to So malia twenty years after he was imprisoned and then sent into exile, Jeebleh arrives at a remote Mogadiscio airport now under the control of a major warlord. He has come from his adopted home in America to help Bile, his oldest friend from childhood, find and rescue his kidnapped daughter and a friend. Bile is affiliated with a warlord in the south of the city, but Jeebleh may be in a particularly good position to help him if the child has been taken by a rival, since he belongs to the same clan as the warlord controlling the north. The political situation is so tangled, however, that at times no one really knows who is allied with whom.

malia twenty years after he was imprisoned and then sent into exile, Jeebleh arrives at a remote Mogadiscio airport now under the control of a major warlord. He has come from his adopted home in America to help Bile, his oldest friend from childhood, find and rescue his kidnapped daughter and a friend. Bile is affiliated with a warlord in the south of the city, but Jeebleh may be in a particularly good position to help him if the child has been taken by a rival, since he belongs to the same clan as the warlord controlling the north. The political situation is so tangled, however, that at times no one really knows who is allied with whom.

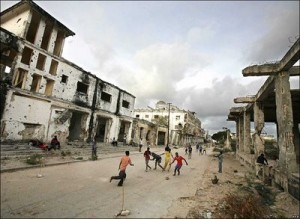

As he travels around the ruins of Mogadiscio, once a beautiful city filled with educated people, Jeebleh comments to an acquaintance: “This city is a disaster. I haven’t met anyone who openly disapproves of what’s happening, and yet the fighting goes on and the clan elders continue soliciting funds for repairing deadly weapons.”

His acquaintance explains, “Here we don’t think of ‘friends’ anymore. We rely on our clansmen…sharing ancestral blood….Every clan family feels that it has to form its own armed militia, because the others have them. The elders, almost all of them illiterate and out of touch with your and my sense of modernity, spend their time trying to raise funds from within the members of the blood community. In truth, it’s all a pose, though, and everybody knows that the elders are doing this to make sure they seem important.”

As he searches for his mother’s unrecorded grave and tries to help Bile recover his daughter Raasta and her little girlfriend, he finds himself becoming divided, emotionally and culturally. Here, in the surroundings in which he grew up, he feels like someone looking at the outside world from inside Somalia, but the environment in which he grew up has changed, just as he has changed from living in the United States, and as he contemplates these changes, he also feels like an outsider looking in. His life is constantly in danger, he is often followed, he sees people gunned down “for fun,” and he has no idea who is friend and who is foe. Unfamiliar with the political territory in which he is operating, he is not sure how, if at all, he will be able to extricate himself from Mogadiscio, even if he succeeds in finding Bile’s daughter.

It is not accidental t hat Jeebleh has received his doctorate for a book he has written on Dante’s Inferno, the symbolic parallel for the existentialist nightmare he sees in Somalia. “We are at best good badmen or bad badmen,” a Somali tells him as he tries to navigate the minefield of loyalties in Mogadiscio. As Jeebleh tries to figure out whether his friend Bile is one of the “good badmen” or “bad badmen” and whether Bile’s half-brother in the north is involved in the kidnapping, we learn about the family history, Somali culture and history, and the mysterious associates of various warlords who want to “help” Jeebleh.

hat Jeebleh has received his doctorate for a book he has written on Dante’s Inferno, the symbolic parallel for the existentialist nightmare he sees in Somalia. “We are at best good badmen or bad badmen,” a Somali tells him as he tries to navigate the minefield of loyalties in Mogadiscio. As Jeebleh tries to figure out whether his friend Bile is one of the “good badmen” or “bad badmen” and whether Bile’s half-brother in the north is involved in the kidnapping, we learn about the family history, Somali culture and history, and the mysterious associates of various warlords who want to “help” Jeebleh.

The novel is filled with high tension as various characters, including Jeebleh, are pulled in different directions by circumstances over which they have no control. His enigmatic dreams and nightmares are much like the reality of life in Mogadiscio, where the vultures are now tame because they are so well fed by the violence. “A cynic I know says that thanks to the vultures, the marabous, and the hawks, we have no fear of diseases spreading,” one of Jeebleh’s contacts says. “My cynical friend suggests that when the country is reconstituted as a functioning state, we should have a vulture as our national symbol.”

Author Farah’s own background as an exiled Somali makes this novel particularly vivid, and the cultural conflicts and the pressures placed on Jeebleh’s family loyalties ring with truth. As he represses his American values and makes some major decisions as a Somali, Jeebleh becomes part of the story of Somalia, “I’ve taken sides and made choices that may put my life in danger.” Stressing that it is “only when there is harmony within the smaller unit,” i.e., the family, that “the larger community finds comfort in the idea of the nation,” Farah creates a taut novel in which the tensions within the family are a microcosm of the tensions within the country. Realistic in its descriptions and allegorical in its implications, Farah’s novel is a breathtaking and sophisticated study of violence and betrayal certain to receive international recognition.

Notes: The author’s photo by Melina Mara appears in http://www.washingtonpost.com

The children playing football in a devastated street appear on http://carleslopezbtx.blogspot.com/

Street scene in Mogadicio: http://www.lastampa.it