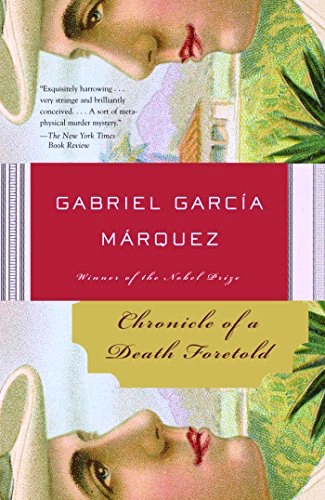

Note: In 1982 Gabriel Garcia Marquez was WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

“On the day they were going to kill him, Santiago Nasar got up at five-thirty in the morning to wait for the boat the bishop was coming on. He’d dreamed he was going through a grove of timber trees where a gentle drizzle was falling, and for an instant he was happy in his dream, but when he awoke he felt completely spattered with bird shit.” – opening lines.

Written in 1981, Chronicle of a Death Foretold tells the story of a killing which took place twenty-seven years before the novel opens. An unnamed narrator has returned to the unnamed town on the Caribbean coast of Colombia where he was a participant in actions which culminated in the killing of Santiago Nasar. As the novel opens in flashback, Nasar, the twenty-one year-old victim of this old crime, has only about an hour left to live as he dreams happily of a grove of timber trees, then awakens to the fact that he is “completely spattered with bird shit,” a darkly humorous parallel to the action which is about to unfold. He has awakened with a headache, a result of the “natural havoc of the wedding revels that had gone on until after midnight,” but he gets up to go to the harbor where he waits to see the bishop sailing into port early in the morning. The narrator, too, is recovering from the wedding celebrations, “in the apostolic lap of Maria Alejandrina Cervantes.” Shifting repeatedly from past to present and back again, the speaker’s recent return to the village almost three decades after the murder, is being done “to put the broken mirror of memory back together from so many scattered shards.”

Written in 1981, Chronicle of a Death Foretold tells the story of a killing which took place twenty-seven years before the novel opens. An unnamed narrator has returned to the unnamed town on the Caribbean coast of Colombia where he was a participant in actions which culminated in the killing of Santiago Nasar. As the novel opens in flashback, Nasar, the twenty-one year-old victim of this old crime, has only about an hour left to live as he dreams happily of a grove of timber trees, then awakens to the fact that he is “completely spattered with bird shit,” a darkly humorous parallel to the action which is about to unfold. He has awakened with a headache, a result of the “natural havoc of the wedding revels that had gone on until after midnight,” but he gets up to go to the harbor where he waits to see the bishop sailing into port early in the morning. The narrator, too, is recovering from the wedding celebrations, “in the apostolic lap of Maria Alejandrina Cervantes.” Shifting repeatedly from past to present and back again, the speaker’s recent return to the village almost three decades after the murder, is being done “to put the broken mirror of memory back together from so many scattered shards.”

Dealing simultaneously with past and present, Chronicle of a Death Foretold appears at first to be a fairly straightforward and unpretentious murder mystery, but it is far more complex than it seems. First, it does not follow the traditional structure of a mystery story, instead shifting back and forth over the course of twenty-seven years as one person who was present at the time of the murder returns to the town many years later to re-examine his memories and those of others. Further, for those familiar with the work of Garcia Marquez, this novel is different from what one usually associates with this author – the action here is neither surreal nor fantastical. Except for a few women who always look for auguries in their everyday lives, the characters all appear to be firmly grounded in reality, leading the reader to question all their actions, relationships, and motives to see what it was that could have inspired the murder at all. With the murder taking place after a three-day wedding celebration, the author keeps the mood upbeat, even humorous in places, as Santiago prepares to go to the port, naively going out the back door while the two men who plan to kill him wait for him at the front. He is in such a hurry that neither he nor anyone else in his house sees a message that has been shoved under the door warning him that he is going to be killed and telling him the place, the motive, and other precise details. All this because the groom, Bayardo San Roman, has returned the bride to her family on their wedding night, and Santiago is thought to be involved.

A steamer with two smoke stacks is carrying the bishop whom Santiago Nasar awaits when he is killed. The bishop does not leave the cupola on the top deck.

Bayardo San Roman, the groom, is a newcomer to town, about thirty years old, who claimed originally that he had been “going from town to town looking for someone to marry.” No one knows if what he says is true, however, “because he had a way of speaking that served to conceal rather than to reveal.” His background is so “reserved” that “even the most demented invention could have been true.” Bayardo’s choice of Angela Vicario as his bride, leaves her unimpressed because, she says, “I detested conceited men, and I’d never seen one so stuck-up.” The son of a general who was a hero of the civil wars of the past century, no one knows much about Bayardo, but somehow Angela is encouraged to change her mind, and the wedding takes place. Later that night, Bayardo carries her back to her house – he has discovered she is not a virgin. Angela is so traumatized that when challenged to name her lover, she is able to do it only after “looking for it in the shadows…among many, many easily confused names from this world and the other.” The next morning Angela’s two brothers – Pedro and Pablo – murder Santiago Nasar, the supposed secret lover, as he awaits the bishop’s arrival at the port.

From here the narrative becomes farcical as the characters must use a substitute to do the autopsy, which becomes more like a massacre, one so messed up that a “helper fainted,” another became a vegetarian on the spot, and body parts were thrown in the garbage pail. Ironically, the person everyone feels sorry for is Bayardo San Román, who remains in an alcoholic stupor after the wedding night, his family so dramatically upset that the narrator suggests that “their [horror] could only be put on, in order to hide other, greater shames.” The Vicario brothers for their crime end up spending three years in the Riohacha jail, and their family moves from Riohacha to Manaure, with its salt mines. Over the ensuing years, the bride, Angela Vicario, discusses the “incident,” but the overall feeling of the community has been that she “was protecting someone who really loved her and she had chosen Santiago Nasar’s name as the traitor because she thought her brothers would never dare go up against him.”

Angela and family move to Manaure, famed for its salt mines, after the wedding and murder. Photo by Maria Angelica Gomez.

For years afterward, no one in the town can talk of anything else and it is obvious that they continue to talk because they all need some kind of exact knowledge of the place, its recent events, and the missions assigned to them by fate. All the uncertainties still remain decades after the events, affecting the lives of every member of the community. Author Gabriel Garcia Marquez provides just enough hints to keep the reader attentive and imagining all the “what-ifs” about the events. The one who learns most from this permanent exercise is the former bride herself, Angela Vicario, who discovers that hate and love are reciprocal passions, on which she herself chooses, finally, to act. Her decision will remain a mystery to readers, however, just as all the other complications of this failed wedding will remain mysteries and guesses. Power, one of Garcia Marquez’s major themes in other novels is more elusive and uncertain here, its sources unclear, and death, usually a big focus of his work, becomes one event among many that deserves more careful scrutiny.

Characters here sometimes refer to drinking cane liquor. Here a man is pressing the cane, to which he will add yeast for fermentation. Note blue bucket catching the syrup.

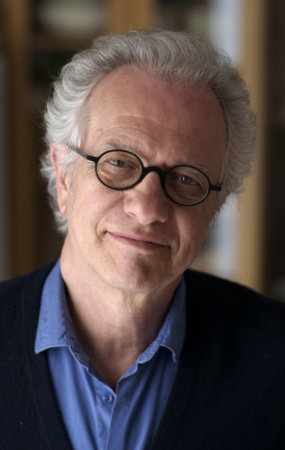

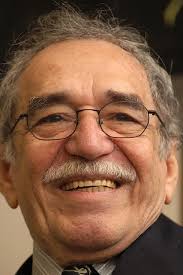

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://en.wikiquote.org/

This paddlewheel steamer with two stacks resembles the one which murder victim Santiago Nasar awaited, hoping to meet the bishop. https://flydango.net

Riohacha Prison is where Pedro and Pablo spent three years in payment for their crime. https://colombiareports.com/inside-colombias-ten-worst-prisons/

A house in Manaure, perhaps similar to the one where Angela Vicario’s family stayed after the murder of Santiago Nasar and the jailing of Pedro and Pablo Vicario for three years. Photo by Maria Angelica Gomez, https://www.expedia.com

Throughout the novel, characters often partake of cane liquor. Here a man is pressing the cane. Note the blue bucket beneath. Some yeast added to the syrup creates the fermentation for this local drink. https://www.smithsonianmag.com

orse, who tells this story of his life as an Ojibwe living in a non-native society, is in his thirties as the novel opens, and he is at the New Dawn Center, an alcohol rehabilitation facility to which he has been sent by social workers at the hospital where he has been a patient for six weeks.

orse, who tells this story of his life as an Ojibwe living in a non-native society, is in his thirties as the novel opens, and he is at the New Dawn Center, an alcohol rehabilitation facility to which he has been sent by social workers at the hospital where he has been a patient for six weeks.

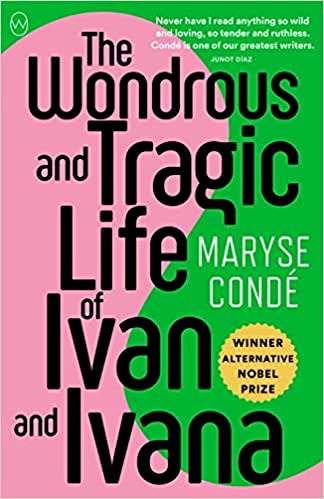

Giving birth alone in Guadeloupe after her lover, Lansana Diarra, returned to his home in Mali, Simone Némélé waited in vain for the ticket he had promised to send her so that she and their newborn twins, Ivan and Ivana, could join him in Mali.

Giving birth alone in Guadeloupe after her lover, Lansana Diarra, returned to his home in Mali, Simone Némélé waited in vain for the ticket he had promised to send her so that she and their newborn twins, Ivan and Ivana, could join him in Mali.

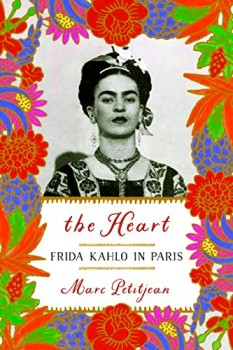

When author Marc Petitjean was contacted in Paris by a Mexican writer named Oscar, who wanted to meet him to talk about Marc Petitjean’s father Michel, the author’s interest was piqued.

When author Marc Petitjean was contacted in Paris by a Mexican writer named Oscar, who wanted to meet him to talk about Marc Petitjean’s father Michel, the author’s interest was piqued.