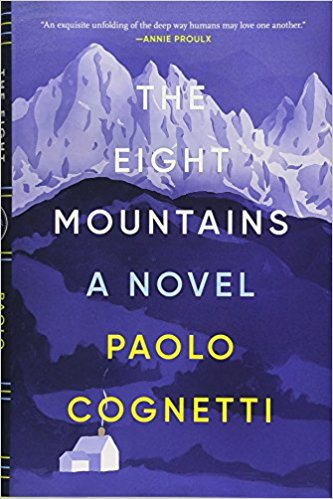

Note: This novel was WINNER of the Strega Prize, Italy’s highest honor, when it was published in Italy in 2017.

“I peered over the rock…I did not know what I was supposed to see: beyond the rock the river formed a small waterfall and a shadowy pool, probably knee-deep. The surface of the water was unsettled, agitated by the churning fall. At the edges floated a finger’s depth of foam, and a large trapped branch sticking out diagonally had collected grass and sodden leaves around itself. It wasn’t much of a spectacle, only water that had run there from the mountain. And yet it was spellbinding: I don’t know why.”—Pietro Guasti, age 12.

In 1984 twelve-year-old Pietro Guasti and his parents arrive in Grana, a quiet mountain village in northern Italy between Turin and Milan. Both parents love climbing the mountains, and though Pietro’s mother, a former nurse, does not enjoy climbing beyond the three-thousand foot mark, his father, who is at heart a loner, routinely climbs to the peaks of the higher mountains which attract him. Grana, a tiny farming village, has been losing its population, but it is in the foothills of Monte Rosa, a well-known climbing location, which makes it attractive as a vacation site, with an atmosphere far different from Pietro’s home in Milan. Pietro becomes fast friends almost instantly with Bruno Guglielmina, a local youth his age who is in charge of his family’s cows. Together they explore the mountain, the abandoned farms, a former school, and other places testifying to the decline of the village economy but fascinating for the images they conjure for the boys.

In 1984 twelve-year-old Pietro Guasti and his parents arrive in Grana, a quiet mountain village in northern Italy between Turin and Milan. Both parents love climbing the mountains, and though Pietro’s mother, a former nurse, does not enjoy climbing beyond the three-thousand foot mark, his father, who is at heart a loner, routinely climbs to the peaks of the higher mountains which attract him. Grana, a tiny farming village, has been losing its population, but it is in the foothills of Monte Rosa, a well-known climbing location, which makes it attractive as a vacation site, with an atmosphere far different from Pietro’s home in Milan. Pietro becomes fast friends almost instantly with Bruno Guglielmina, a local youth his age who is in charge of his family’s cows. Together they explore the mountain, the abandoned farms, a former school, and other places testifying to the decline of the village economy but fascinating for the images they conjure for the boys.

The quotation which opens this review is Pietro’s reaction to an experience he has in the mountains with Bruno, a place which Pietro does not recognize, at first, for the “miracle” that it is. As he stares at the water, however, Pietro suddenly realizes that “there was something moving beneath it…four tapering shadows with their snouts facing into the current, with only their tails moving slowly from side to side.” What Pietro finds so remarkable is that “we were further down the valley than they were, which was why they had not noticed us yet.” The fish – trout – were hunting, giving the lie to the idea that fish swim with the current, something Bruno knew already because he had observed it. This very early scene is in many ways symbolic of this novel itself, a consummately quiet, peaceful novel in which nothing much “happens.” Yet it is magical, even for those of us who do not fish for trout or climb mountains, a novel in which the author follows Pietro and Bruno from the age of twelve until they are in their early forties.

On his first climb with his father, Pietro is excited to see ibexes watching them, even as he is miserable from altitude sickness.

The reader comes to know Pietro and Bruno both separately and as members of their very different families, and as their lives continue to overlap in summers and, later, through Pietro’s separate visits to the village, their mutual respect, even love, for each other is a constant theme which provides a kind of anchoring stability even when they move in very different directions. A key component of their relationship, at first, is the presence of Pietro’s father, a hardworking, conscientious man with a desk job, a man who reveals little of himself to his son Pietro, but who has an instinctive connection with Bruno. A casual invitation to Bruno to join Pietro and his father for Pietro’s first big climb up the mountain becomes symbolic, as the father, rigidly focused on reaching the top of this 3000-foot peak, finds himself drawn more closely to Bruno, whose physical size and abilities make him a great, if untutored, climber, while his own son Pietro soon finds himself suffering the agony of altitude sickness, which he is afraid to reveal.

Two summers later, Pietro’s mother is waging war with Bruno’s family trying to ensure that Bruno, who has little interest in schooling, gets an education, and a confrontation with Bruno’s father ensues. Pietro’s own decision to stop participating in further camping experiences provides emotional blows to his father, who continues to climb on his own. Pietro begins short term rock climbing instead, with some of the wealthy tourists who have come to the mountain for vacations, and his father is devastated by his participation in what he regards as a lesser “social activity.” As he leaves Grana that summer, Pietro also leaves Bruno, and does not return for fourteen years. When he does return at age thirty-one, he reveals that he has moved from Milan to Turin to be on his own and lives in a studio flat. He is earning a living as a documentary filmmaker, is still single, and is still alienated from his father.

Turin, to which Pietro moved when his family life in Milan became too stifling. Grana is located between Milan and Turin.

Eventually, a special bequest from his father leads Pietro back to Grana and to Bruno, now a builder. When Bruno persuades Pietro to stay for the summer to help him rebuild an old house, Pietro decides to stay, gradually getting into better physical shape, climbing the mountain again and revisiting special places. At the end of summer, Pietro moves on to Asia, to make a film about the most dangerous mountain of all, Annapurna in the Himalayas, while Bruno stays in Grana with a woman who loves him. In the Himalayas, Pietro meets an old Nepalese man who provides a much-needed perspective about life: “The [old Nepalese] man picked up a small stick and drew a circle with it on the ground. Then, inside the circle he [drew]…a wheel with eight spokes [a mandala]….We believe that at the centre of the earth there is a tremendously high mountain, Sumeru,” he says. “Around Sumeru there are eight mountains and eight seas. This is the world for us…We ask who has learned the most, the one who has been to all eight mountains, or the one who has reached the summit of Sumeru?” As the novel winds its way to its conclusion, the answer to this mystical question becomes clearer.

The action throughout is quiet and thought-provoking, leaving the reader to sort through the various subplots and what they mean to both Pietro and Bruno as they try to find success – not financial success, but personal, emotional success – a sense of achievement based on effort and care for others. In this, the novel, which some refer to as a coming-of-age novel, expands its themes and its characters as some face a future which they may not have been expecting. Ultimately, Pietro has learned, unexpectedly from his father, that there may be certain mountains to which one can never return, and that visiting the eight mountains is all that remains for some. A surprising and very satisfying novel certain to appeal to those who appreciate understated, leisurely writing with much of value to say, and book clubs should love it.

ALSO by Cognetti, THE WILD BOY

Photos. The author’s photo appears on http://www.lecturissime.com

Pietro is excited when he sees an ibex while climbing, despite the fact that he is suffering from altitude sickness, which he does not want to tell his father for fear of disappointing him. http://www.cicukteb.com/

The massif of Monte Rosa faces them when they reach the summit: https://www.alpineinterface.com

Grana is located about halfway between Milan, where Pietro lived as a child, and Turin, shown here, to which he moved as an adult. https://www.10thingstodoandsee.com

Pietro plans to do a documentary about Annapurna in the Himalayas, the most dangerous mountain climbing experience of all. https://en.wikipedia.org

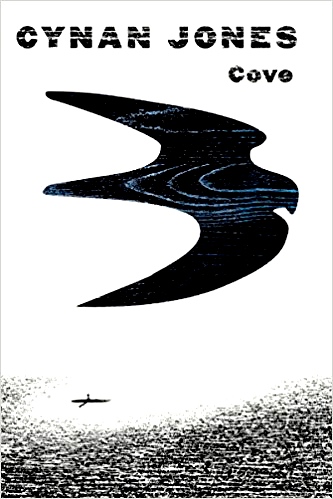

Cove, a novella by Welsh author Cynan Jones, so perfectly captures the mind and heart of its main character that many readers will read it in one sitting and then go back and reread all or most of it. An experimental novel in which the narrator’s individual thoughts are set off in separate paragraphs on wide-margined pages, the narrative hovers between a sharp, detailed, almost journalistic depiction of a speaker who goes out to sea in his kayak to scatter his father’s ashes, and some equally sharp, detailed pictures of what may be his hallucinations. All observations are the same for the speaker after a sudden storm and a lightning strike at sea leave him seriously injured, hungry, thirsty, and sometimes incoherent. Though he is well trained in the safety procedures which he recognizes may make the difference between his life and death at sea, he has gone out alone in his kayak, without informing the woman he loves, who is pregnant: He had hoped to spend this one last day with his father, in private.

Cove, a novella by Welsh author Cynan Jones, so perfectly captures the mind and heart of its main character that many readers will read it in one sitting and then go back and reread all or most of it. An experimental novel in which the narrator’s individual thoughts are set off in separate paragraphs on wide-margined pages, the narrative hovers between a sharp, detailed, almost journalistic depiction of a speaker who goes out to sea in his kayak to scatter his father’s ashes, and some equally sharp, detailed pictures of what may be his hallucinations. All observations are the same for the speaker after a sudden storm and a lightning strike at sea leave him seriously injured, hungry, thirsty, and sometimes incoherent. Though he is well trained in the safety procedures which he recognizes may make the difference between his life and death at sea, he has gone out alone in his kayak, without informing the woman he loves, who is pregnant: He had hoped to spend this one last day with his father, in private.

The dawn continues on its way, finding Anita in her kitchen, wearing a gray pullover that belongs to her husband Adam. She has had a sleepless night, thinking about the old days, her forgotten dreams, about things left undone, and about Adele. The dawn enters the bedroom belonging to Laura, daughter of Anita and Adam, as she dreams that she is swimming in the lake – except she has forgotten that for the past four years, five months, and thirteen days she has been unable either to run or to perform swan dives, or to swim. As the dawn moves on, it “bathes the house and the forest in a dove gray color and makes its way across the fields and the mountain villages. When it reaches the front of the prison complex surrounded by barbed wire, Adam is on his feet, his face pressed against the little window, gripping the bars with both hands…waiting for the dawn, as he has been waiting for his release for four years, five months and thirteen days.” He thinks about the old days, the promises not kept, and about Adele. Standing there barefoot, he is, at last, “looking the dawn in the eye.”

The dawn continues on its way, finding Anita in her kitchen, wearing a gray pullover that belongs to her husband Adam. She has had a sleepless night, thinking about the old days, her forgotten dreams, about things left undone, and about Adele. The dawn enters the bedroom belonging to Laura, daughter of Anita and Adam, as she dreams that she is swimming in the lake – except she has forgotten that for the past four years, five months, and thirteen days she has been unable either to run or to perform swan dives, or to swim. As the dawn moves on, it “bathes the house and the forest in a dove gray color and makes its way across the fields and the mountain villages. When it reaches the front of the prison complex surrounded by barbed wire, Adam is on his feet, his face pressed against the little window, gripping the bars with both hands…waiting for the dawn, as he has been waiting for his release for four years, five months and thirteen days.” He thinks about the old days, the promises not kept, and about Adele. Standing there barefoot, he is, at last, “looking the dawn in the eye.”

After I remarked to some book friends that one of the joys of having finished my schooling and my teaching career was that I would never again have to read a novel by Henry James, both of these friends responded that I really should read The Beast in the Jungle (1903), which they found to be quite different from many of his other works. Though I admit to having loved some of the films of James’s novels, I did not love reading any of the six novels I had had to read for classes, and I have always found James’s prose style to be so contorted, by today’s standards, and so artificial, that I have often had reread and “translate” it into less formal English in order to come close to understanding what James is saying. My friends persuaded me by their enthusiasm, however, and I decided to try reading Henry James again after so many years of avoiding him. Voluntarily returning to his company, it turned out, was a mixed blessing. I admired much of the book and, for the first time, I really began to feel as if I were beginning to know who Henry James really was as a man, not just as a writer. The Beast in the Jungle parallels what we know of his life very closely, and it feels so autobiographical that the reader cannot help but believe that it is based on a very real inner turmoil in his life and may also explain some the mysteries which have always surrounded him.

After I remarked to some book friends that one of the joys of having finished my schooling and my teaching career was that I would never again have to read a novel by Henry James, both of these friends responded that I really should read The Beast in the Jungle (1903), which they found to be quite different from many of his other works. Though I admit to having loved some of the films of James’s novels, I did not love reading any of the six novels I had had to read for classes, and I have always found James’s prose style to be so contorted, by today’s standards, and so artificial, that I have often had reread and “translate” it into less formal English in order to come close to understanding what James is saying. My friends persuaded me by their enthusiasm, however, and I decided to try reading Henry James again after so many years of avoiding him. Voluntarily returning to his company, it turned out, was a mixed blessing. I admired much of the book and, for the first time, I really began to feel as if I were beginning to know who Henry James really was as a man, not just as a writer. The Beast in the Jungle parallels what we know of his life very closely, and it feels so autobiographical that the reader cannot help but believe that it is based on a very real inner turmoil in his life and may also explain some the mysteries which have always surrounded him.

Unusual and perhaps even unique for an American audience, Moshe Sakal’s The Diamond Setter follows three generations of several interconnected families as they move though Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, and eventually Israel, following their dreams and their hopes for their families over the course of a century. Narrated in the present by Tom, much of the novel is a metafictional account of his life and his involvement in events surrounding a magnificent blue diamond which has been in the possession of members of his extended family for several generations. The diamond, despite its intriguing story, is not the primary focus here, however. Rather, it is the belief of the diamond’s possessors that the diamond has a mind of its own – and that it can affect their lives in unexpected ways. Over the generations, many have believed that the diamond is, in fact, cursed, and so they often hide it for the time that it is in their possession and live their own lives as well as they can without recourse to its “magic.”

Unusual and perhaps even unique for an American audience, Moshe Sakal’s The Diamond Setter follows three generations of several interconnected families as they move though Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, and eventually Israel, following their dreams and their hopes for their families over the course of a century. Narrated in the present by Tom, much of the novel is a metafictional account of his life and his involvement in events surrounding a magnificent blue diamond which has been in the possession of members of his extended family for several generations. The diamond, despite its intriguing story, is not the primary focus here, however. Rather, it is the belief of the diamond’s possessors that the diamond has a mind of its own – and that it can affect their lives in unexpected ways. Over the generations, many have believed that the diamond is, in fact, cursed, and so they often hide it for the time that it is in their possession and live their own lives as well as they can without recourse to its “magic.”