Fiete plucked something from the carpet on the altar steps. “And that, ladies and gentlemen, concludes our segment on ‘How to have a Happy War’.” His somber voice made him sound like a cinema advertisement: “Rope too tight for you? Bullets too fast? Then why not try lovely sepsis! Three weeks of convulsions in a sickbed, nice and warm in your own shit, and at last you’ll hear angels singing. Free to party members, and for regular people it’s available for the low, low price of one human life.”—Fiete, Walter’s cynical friend.

A caveat. I almost did not read this book. Our current political situation and all the anger generated daily in the news and on TV had me longing for something fun and funny to read, something to break the monotony of our nasty political reality. This book focuses on the horrors of World War II from the point of view of two rural German teenagers who get drafted, and that was not what I had in mind for a relaxing read. I started it, however, and as I became involved with the very real – and very naïve – main characters as they faced the terrifying, life-changing situations of war, I found myself emerging from the stupor of TV reality into a much bigger, more comprehensive world view. The subject matter is harrowing, but this sensitively written book generates an enormous amount of empathy for its very human main characters as they come to terms with who they are, where they are, and how they must cope with a war they know is already lost. Ultimately, I was able to escape the pettiness of the latest news cycle. I could appreciate the confidence with which the author develops big ideas for a world audience, and I felt the much-needed thrill of having read something that was sadly enlightening but presented on a level more elevated than anything I could have imagined if I had looked for something “fun.”

A caveat. I almost did not read this book. Our current political situation and all the anger generated daily in the news and on TV had me longing for something fun and funny to read, something to break the monotony of our nasty political reality. This book focuses on the horrors of World War II from the point of view of two rural German teenagers who get drafted, and that was not what I had in mind for a relaxing read. I started it, however, and as I became involved with the very real – and very naïve – main characters as they faced the terrifying, life-changing situations of war, I found myself emerging from the stupor of TV reality into a much bigger, more comprehensive world view. The subject matter is harrowing, but this sensitively written book generates an enormous amount of empathy for its very human main characters as they come to terms with who they are, where they are, and how they must cope with a war they know is already lost. Ultimately, I was able to escape the pettiness of the latest news cycle. I could appreciate the confidence with which the author develops big ideas for a world audience, and I felt the much-needed thrill of having read something that was sadly enlightening but presented on a level more elevated than anything I could have imagined if I had looked for something “fun.”

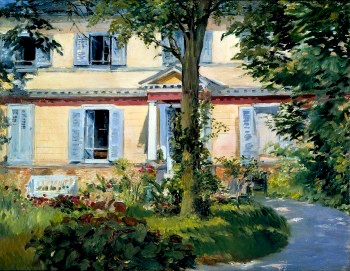

As the novel opens, an unnamed young man is remembering the life of his father, a man haunted by the past, someone who “lived his whole life in silence.” The boy describes how handsome his father was, how helpful to his neighbors, and even what he wore, but he had never been able to get inside his father, Walter Urban, who spent his life virtually alone. “His was the seriousness of someone who had seen something more potent than the others, who knew more about life than he could say and who sensed that even if he had the language to express what he had seen, there would be no redemption for him.” When Walter Urban retired, his son gave him a notebook and asked him to sketch out his life, writing down the major events from the years before his son was born, but Walter wrote only a few words, feeling that there was no point to it. A dairyman who had worked on a farm resembling Edouard Manet’s “Country House in Rueil,” Walter became a miner later in life, and became deaf from his work. He eventually suffered a stroke, and he was left virtually mute, a condition which led his son believe that “he wasn’t unhappy in his unquestioning silence.”

The manor house on the farm where Walter was a dairyman is described as resembling Manet’s “Landhaus in Rueil.”

The previously untold story of Walter Urban’s younger life begins immediately after this and becomes the novel, with only a brief paragraph of introduction, related to an underlined passage in the family Bible, “When thou tillest the ground, it shall not henceforth yield unto thee her strength…A fugitive and vagabond shalt thou be in the earth.” Walter’s own feeling of being a “fugitive and vagabond” may or may not have evolved from the events described here, but his son’s need to explain how and why he thinks his father became so withdrawn, and his ability to see into his father’s psyche is so important to him that that readers will believe every word. Walter is seventeen as the story of his life opens, as recreated here by his son after his death, and what Walter has heard on “enemy stations” on the radio has convinced him that the war is nearly over. Working with him at the dairy farm is his close friend, Fiete Caroli, an eighteen-year-old who is his opposite. Fiete takes chances, drinks to excess, plays around with girls, and is dedicated to having as much fun as possible.

At the community hall one evening, a heavily scarred, one-armed German SS officer stands up and makes a speech, bullying “everyone who loves his family and his native soil and who can hold a rifle…to join the victorious Waffen-SS. We owe that to our heroes at the front.” Now drunk on the beer supplied by the officer, Fiete decides to enlist, and he drags Walter with him, both of them believing that the war “will probably be over before we’ve finished training.” They have no training, and soon they are on their way to Budapest to fight. Fiete will be on the front lines, and Walter, who has a driver’s license, is assigned to a supply unit. Almost immediately, Walter and his unit arrive at a farm at which the owners and workers are tied up, ready to be hanged, supposedly for being partisans. Walter stands up for them on the grounds that these are the “nice people” who had provided a place for him and others to spend the night the previous night, but to no avail. He is “handled” by the officer who tells him to “Stop your opera singing! You’re inches away from crying…Partisans, Jews, who cares?” and the hangings begin. As the convoy continues toward Budapest, the sadism of the German officers becomes more pronounced as the futility of the German position becomes more obvious. When Walter has a chance to talk with an influential officer to ask for permission to look for the grave of his father, who has been killed in action in one of the many towns they are passing through, he is granted three days as a reward for a favor he has done.

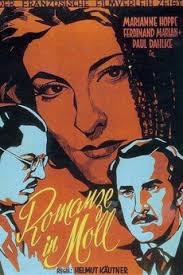

As he searches for his father’s grave on the way back to his rural home, Walter takes time to see a recent movie, ROMANCE IN A MINOR KEY, a film based on Guy de Maupassant’s short story, “Les Bijoux.”

While exploring nearby towns looking for his father’s grave, he discovers that Fiete is in the basement of one building, under lock and key. He has deserted, and is awaiting punishment. From here on, everything happens at warp speed, and Walter returns to his unit. Some information comes from home via letters which still manage to find him, and the terrain and the towns become more familiar as Walter and his unit get closer home. Along the way, they explore places they know, even escaping to a popular film, at one point. The action moves increasingly fast and becomes more abbreviated in description, the closer Walter gets to the dairy farm where he lived and worked. He expresses his inner thoughts less often, noticeably removing himself from activity, thereby preserving what is left of his sanity. An Epilogue from Walter’s son, the author of the “memoir,” brings the themes of life and death, innocence and guilt, responsibility and accountability, and power and futility to their climax. This powerful novel wastes no words, much like Walter himself. Superb!

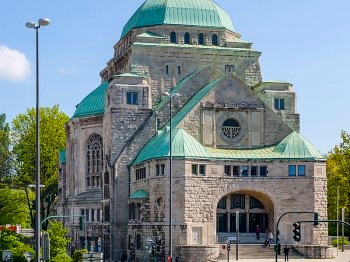

When Walter gets to Essen, near his home, he discovers that the Synagogue has hardly been touched by the war, “and one might have been tempted to think of something like mercy, a protecting power.”

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/

Monet’s “Landhaus in Rueil,” described as similar to the manor house where Walter works as a dairyman is from https://commons.wikimedia.org

A damaged BMW R75 motorcycle is the only vehicle that Walter has available to use as he searches for the burial place of his father, killed in the war in one of the towns through which he is traveling. http://i.imgur.com/

Walter and friends, still teenagers, see a recent German film as they travel back to their homes near the end of the war. “Romance in a Minor Key” is described as Kautner’s best film of the period and is an adaptation of Guy de Maupassant’s short story, “Les Bijoux.” https://letterboxd.com/film/romance-in-a-minor-key/

On the night before an auction of world-class paintings, thirty-something Matt Santos gets permission to spend the night at the auction house “saying goodbye” to “Budapest Street Scene,” painted in 1925 by Hungarian artist Ervin Kalman. Although Matt is considered the owner of the painting, he has, in fact, just recently learned about his connection to the painting as part of the on-going repatriation efforts made for paintings stolen by the Nazis. Matt has a family picture of his grandfather’s living room in Budapest, in which the painting is shown on the wall, but he has never known anything about it in real life, and when investigators finally tracked him down and told him that the painting would be “returned” to him, he could not understand why his estranged father had already refused to accept it, even though it is worth millions of dollars. As he spends the night staring at the painting and thinking about his family, what he knows of their history in Hungary, and how he relates to them in the present, he is accompanied only by a night watchman from the Vigil security firm, a man he addresses as “Virgil” in this vibrant, novel-length monologue.

On the night before an auction of world-class paintings, thirty-something Matt Santos gets permission to spend the night at the auction house “saying goodbye” to “Budapest Street Scene,” painted in 1925 by Hungarian artist Ervin Kalman. Although Matt is considered the owner of the painting, he has, in fact, just recently learned about his connection to the painting as part of the on-going repatriation efforts made for paintings stolen by the Nazis. Matt has a family picture of his grandfather’s living room in Budapest, in which the painting is shown on the wall, but he has never known anything about it in real life, and when investigators finally tracked him down and told him that the painting would be “returned” to him, he could not understand why his estranged father had already refused to accept it, even though it is worth millions of dollars. As he spends the night staring at the painting and thinking about his family, what he knows of their history in Hungary, and how he relates to them in the present, he is accompanied only by a night watchman from the Vigil security firm, a man he addresses as “Virgil” in this vibrant, novel-length monologue.

Alan Parks lived for years in Glasgow, Scotland, the place where he has set his debut novel – and the same place where revered author William McIlvanney set his three

Alan Parks lived for years in Glasgow, Scotland, the place where he has set his debut novel – and the same place where revered author William McIlvanney set his three

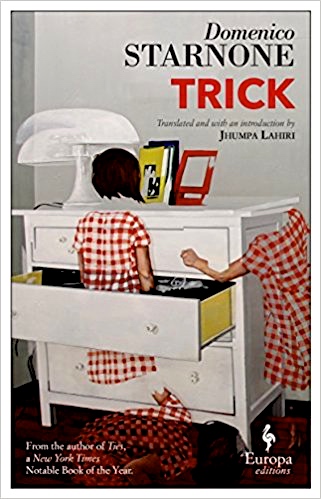

Daniele Mallarico, in his seventies, is on his way from Milan to Naples, where he has agreed to care for his four-year-old grandson Mario for three days so that his daughter and son-in-law can attend a professional mathematics conference. Daniele, already late with illustrations he has agreed to create for a new edition of Henry James’s “The Jolly Corner,” has been ill, and he and his daughter have not been close, even during and after his recent surgery. He has not seen his only grandchild for two years. The house where he will be staying, however, is the one in which he grew up – and where he has left ghosts – part of an elegant, centuries-old building overlooking the busy Piazza Garibaldi in Naples. Mallarico’s arrival in Naples begins author Domenico Starnone’s novel and is quite different from what one would expect from the above summary, the many blurbs on-line and on the book’s back cover, and the novel’s obviously “cute” cover illustration. For unknown reasons, the chosen cover shows ghostly images of a curious school-age girl exploring a modern, painted bureau, neither of which plays any role at all in this thoughtful literary novel.

Daniele Mallarico, in his seventies, is on his way from Milan to Naples, where he has agreed to care for his four-year-old grandson Mario for three days so that his daughter and son-in-law can attend a professional mathematics conference. Daniele, already late with illustrations he has agreed to create for a new edition of Henry James’s “The Jolly Corner,” has been ill, and he and his daughter have not been close, even during and after his recent surgery. He has not seen his only grandchild for two years. The house where he will be staying, however, is the one in which he grew up – and where he has left ghosts – part of an elegant, centuries-old building overlooking the busy Piazza Garibaldi in Naples. Mallarico’s arrival in Naples begins author Domenico Starnone’s novel and is quite different from what one would expect from the above summary, the many blurbs on-line and on the book’s back cover, and the novel’s obviously “cute” cover illustration. For unknown reasons, the chosen cover shows ghostly images of a curious school-age girl exploring a modern, painted bureau, neither of which plays any role at all in this thoughtful literary novel.

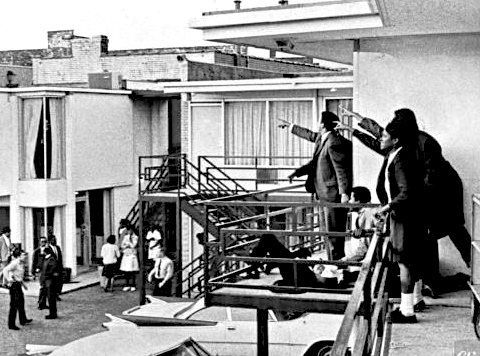

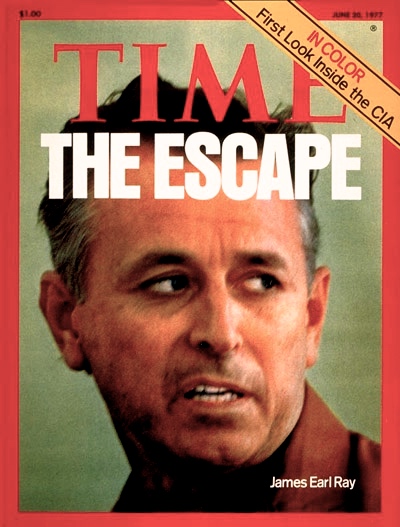

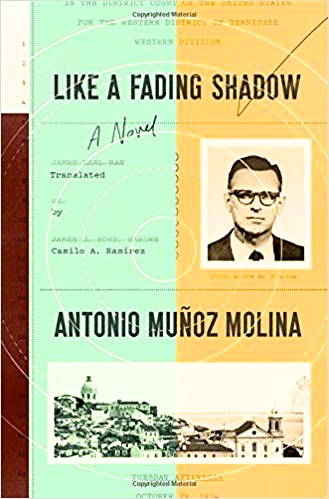

In this fascinating, involving, often hypnotic novel, Spanish author Antonio Munoz Molina creates a compelling story from several points of view and several different time periods, revolving around the life of James Earl Ray and his eventual murder of Martin Luther King in Memphis on April 4, 1968. Munoz Molina gives Ray’s story a different slant from purely journalistic accounts, concentrating on his life, his past, and his thoughts, and culminating in his two escapes – the first time in 1967, a year before the assassination, when he escapes from a Missouri prison and moves throughout the US and Canada for months, eventually living in Mexico. Leaving Mexico in November, 1967, he returns to the US, supports the Presidential campaign of George Wallace, has some facial reconstruction surgery, and considers emigrating to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), then under the rule of a white minority. Eventually, he gravitates to Memphis, where he commits the murder of Dr. King and escapes, first to Canada, then to London, Lisbon, and back to London, where he is apprehended. Though Munoz Molina often details the thoughts of James Earl Ray, he uses an unusual third person point of view, combining his journalistic skills regarding events and places with the fictionalized inner personality and emotions of Ray as he lives and travels, providing a kind of literary energy which goes beyond the limits of narrative reporting.

In this fascinating, involving, often hypnotic novel, Spanish author Antonio Munoz Molina creates a compelling story from several points of view and several different time periods, revolving around the life of James Earl Ray and his eventual murder of Martin Luther King in Memphis on April 4, 1968. Munoz Molina gives Ray’s story a different slant from purely journalistic accounts, concentrating on his life, his past, and his thoughts, and culminating in his two escapes – the first time in 1967, a year before the assassination, when he escapes from a Missouri prison and moves throughout the US and Canada for months, eventually living in Mexico. Leaving Mexico in November, 1967, he returns to the US, supports the Presidential campaign of George Wallace, has some facial reconstruction surgery, and considers emigrating to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), then under the rule of a white minority. Eventually, he gravitates to Memphis, where he commits the murder of Dr. King and escapes, first to Canada, then to London, Lisbon, and back to London, where he is apprehended. Though Munoz Molina often details the thoughts of James Earl Ray, he uses an unusual third person point of view, combining his journalistic skills regarding events and places with the fictionalized inner personality and emotions of Ray as he lives and travels, providing a kind of literary energy which goes beyond the limits of narrative reporting.