“Lilacs were blooming in Cracauerplatz. The Visitor felt disoriented and alone, an outsider, lost without a map. Her atrophied German stuck in her throat. Thirty-one years had elapsed between her last day in Germany…and her return to Berlin in late middle age. The city struck her as post-apocalyptic – flat and featureless except for the rivers, its lakes, it legions of bicyclists. She found herself nameless: nameless in crowds, nameless alone. Another disappearance in a city with a long history of disappearance acts.”

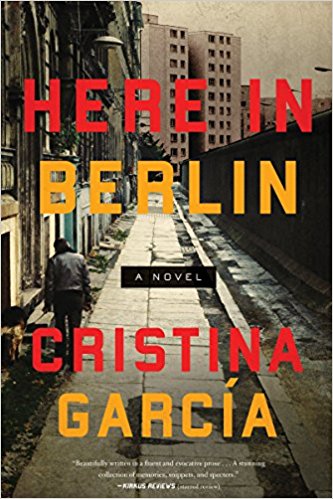

Returning to Berlin for the first time since 1986 and renting an apartment in Charlottenburg in the western part of Berlin, author Cristina Garcia has much on her mind – the end of her second marriage, a final rupture with her impossibly difficult mother, and the feeling that she no longer has a home. Though her family was one of the first families from Cuba to escape to New York and settle following the Castro takeover in 1959, the family is dysfunctional, with serious problems the author spends a whole book discussing in The Lesser Tragedy of Death, the title itself giving an idea of just how dysfunctional they actually are as they face day to day life. Following college and graduate school in the 1970s, Garcia accepted a job in West Germany for a few months, which gave her some distance from her own problems. Now thirty-one more years have passed, and Garcia has returned to Berlin for the first time since then. She is fascinated by some of the people she meets there, and, wanting to record their stories without intruding, she creates a “Visitor” as a stand-in for herself, a third person narrator. Here she does not tell the stories of these people so much as introduce them and then allow each of the thirty-five characters the freedom to tell their stories in their own way. As she “listens” to these stories, she and the reader share the same vantage point – and the stories come to life in unique ways, some of them so “new” that most readers will become spellbound, wondering why they never thought to ask the questions about life in Germany that these characters are answering without being asked.

Returning to Berlin for the first time since 1986 and renting an apartment in Charlottenburg in the western part of Berlin, author Cristina Garcia has much on her mind – the end of her second marriage, a final rupture with her impossibly difficult mother, and the feeling that she no longer has a home. Though her family was one of the first families from Cuba to escape to New York and settle following the Castro takeover in 1959, the family is dysfunctional, with serious problems the author spends a whole book discussing in The Lesser Tragedy of Death, the title itself giving an idea of just how dysfunctional they actually are as they face day to day life. Following college and graduate school in the 1970s, Garcia accepted a job in West Germany for a few months, which gave her some distance from her own problems. Now thirty-one more years have passed, and Garcia has returned to Berlin for the first time since then. She is fascinated by some of the people she meets there, and, wanting to record their stories without intruding, she creates a “Visitor” as a stand-in for herself, a third person narrator. Here she does not tell the stories of these people so much as introduce them and then allow each of the thirty-five characters the freedom to tell their stories in their own way. As she “listens” to these stories, she and the reader share the same vantage point – and the stories come to life in unique ways, some of them so “new” that most readers will become spellbound, wondering why they never thought to ask the questions about life in Germany that these characters are answering without being asked.

The first memory is that of a young boy whose father was the Berlin Zoo’s last keeper. The boy, Helmut Bauer, reminisces about helping to feed the animals on weekends and shares memories of the idiosyncrasies of some animals, like Jupp, a cheetah, “who insisted on having his hindquarters scratched with a rake.” He remembers that his father loved the aviary and that he “borrowed” a Cuban parrot and brought it home to save it from starvation, only to have it disappear during an air raid and vanish (to become somebody’s supper). Surprisingly, his father, at almost fifty and arthritic, is called to war. Later he is one of the few who returns – catatonic – “a man whose happiness had [once] seemed to me as predictable as the sun.” When his father dies five year later, the boy has one wish, “I long to send letters to the past…but who would write back?” The plethora of detail, the child’s point of view, the conversational tone, and the honesty of the boy’s reactions make this short memoir come to life, and it sets the tone for the thirty-four other stories that unfold immediately afterward.

One teen working in Havana as a night watchman is kidnapped by Germans who force him back to their submarine and depart with him aboard. For five months he accompanies them as they move up the East Coast of the United States, coming onto land secretly at night to steal food. When they return the boy to Cuba after that time, no one in Cuba believes his story. A young girl whose grandmother is Jewish, is hidden for thirty-seven days in the sarcophagus of a coal magnate before she can be sent out of the country. A young nurse, who is also an unwed mother, is desperate to leave her hometown and volunteers to go to the Eastern front, where she discovers that her job is to dispense with life instead of to heal. Another character is the daughter of a man who once ran a notorious Berlin sex club in the 1970s, in which the male characters were dressed in authentic Nazi uniforms and put on shows about the intoxication of power to still-sympathetic audiences. One woman who always thought of her grandfather as a war hero from Cuba, learns that he did not fight with the Allies. Instead, he had answered Franco’s call to help the Nazis fight Bolshevism in Spain, Italy, and North Africa.

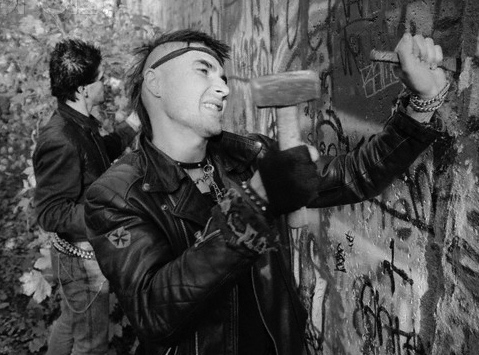

Like these stories, other stories also cast light on the lives of the ordinary Germans who survived the war or who told their stories to their children or grandchildren. One speaker is the granddaughter of parents who volunteered her mother as a young teen to be a breeder of Aryan babies, in exchange for a cash bonus. She, one of the babies, was raised as part of a group, without affection, by a team of nurses who eventually abandon them in 1945, leaving them on their own trying to survive. She is still unable to “feel” the way most human beings do, and, she says, she has never experienced joy. Another woman has spent her life interrogating old Nazis and investigating war crimes, one of only six lawyers in the entire country to investigate the thousands of individual crimes that have been reported, with only fourteen crimes having been adjudicated by the government’s courts. Still another woman, a ballet dancer, danced to survive with a broken foot, eventually becoming crippled, but still had a dalliance with Fulgencio Batista, President of Cuba. An additional character has been the punk bassist for the most notorious East German band of the 1970s. A boy who grew up as a gypsy recognizes the Visitor as a scholar and declares that “Poetry is in the living. Nobody in the world can teach you that.”

Oskar Matzerath, from Gunter Grass’s THE TIN DRUM, is an image that reappears here.

Though the individual stories are unique, brilliant in their execution, and enlightening, even for readers who have read dozens of books about postwar Germany, Cristina Garcia performs magic by opening up even more new thematic threads and suggesting dozens of issues which most of us have not yet even thought to explore. She connects several characters with each other throughout the book to add to the coherence: A retired boxer who is a former pilot; an African eye surgeon from Luanda; characters from the death camp at Sachsenhausen; a Cuban transvestite named Sylvia; a crippled ballerina; and Mazerath, the main character in Gunter Grass’s The Tin Drum, among others, provide some continuity among the stories. With or without these connections, however, the book opens eyes in new ways, quietly questioning our long-held conclusions about Germany before, during, and after the war. As for the Visitor (author), she now wants “Quiet, resplendent days in the light. Her daughter a breath away. And a butterfly net with which to swipe the air, trapping bits of flying color here and there. Yes, she might spend the rest of her life doing nothing more than that.”

ALSO by Cristina Garcia: THE LESSER TRAGEDY OF DEATH

Photos. The author’s photo appears on http://therumpus.net

The German submarine, Type IIB, from 1943, may have been like the one which captured the teenage boy in an early story from this book. http://www.icm.com

Roto, a character from a punk rock band, appears in this novel and may have resembled this person from the GDR in the 1980s. http://1.bp.blogspot.com/

Oscar Matzerath, a character from Gunter Grass’s THE TIN DRUM, appears more than once in this novel, providing some continuity among the characters. http://tvtropes.org/

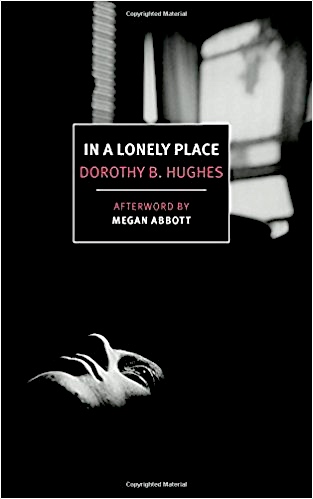

Dickson Steele, a fighter pilot in the Army Air Corps during World War II, has arrived in Los Angeles after wandering, post-war, through Europe and parts of the US, unable to settle down and permanently dissatisfied with his life and his prospects. In Los Angeles, he hopes for a life of excitement as he works on a novel, but even though he has an uncle who has agreed to support him for a year as he works on his book, and has a friend who has loaned him his own elegant, fully-furnished apartment in Beverly Hills while he is away on business, he knows in his heart that nothing will ever quite equal “that feeling of power and exhilaration and freedom that [comes] with loneness in the sky.” He has recently discovered that there is a touch of that loneness at night at the beach, when he looks down from above “at the ocean rolling endlessly in from the horizon,” and when he “put out his hand to the mossy fog as if he would capture it… [he sees] “his hand as a plane passing through a cloud,” a memory which makes him smile.

Dickson Steele, a fighter pilot in the Army Air Corps during World War II, has arrived in Los Angeles after wandering, post-war, through Europe and parts of the US, unable to settle down and permanently dissatisfied with his life and his prospects. In Los Angeles, he hopes for a life of excitement as he works on a novel, but even though he has an uncle who has agreed to support him for a year as he works on his book, and has a friend who has loaned him his own elegant, fully-furnished apartment in Beverly Hills while he is away on business, he knows in his heart that nothing will ever quite equal “that feeling of power and exhilaration and freedom that [comes] with loneness in the sky.” He has recently discovered that there is a touch of that loneness at night at the beach, when he looks down from above “at the ocean rolling endlessly in from the horizon,” and when he “put out his hand to the mossy fog as if he would capture it… [he sees] “his hand as a plane passing through a cloud,” a memory which makes him smile.

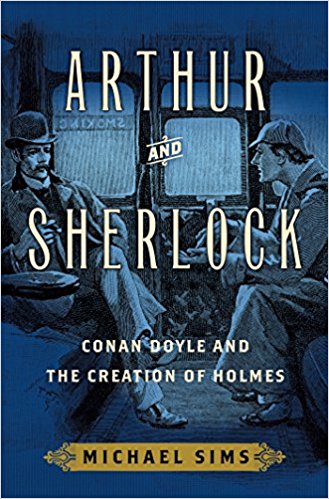

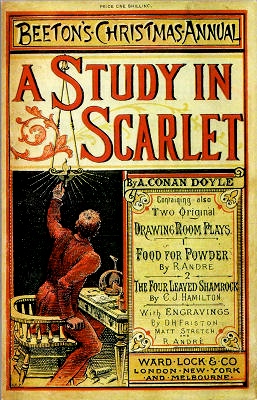

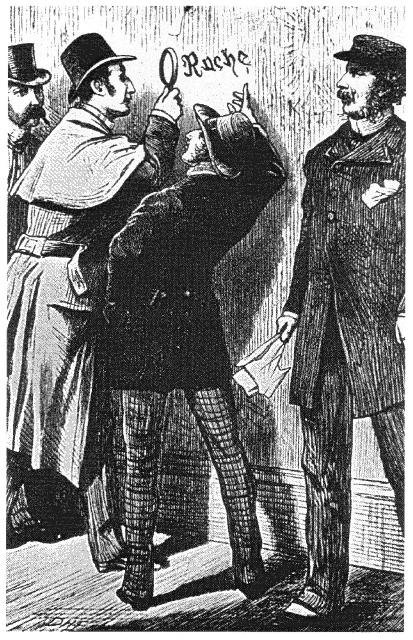

Written as a biography, not of Arthur Conan Doyle’s life but of the specific influences on his life which led to his successful creation of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson as fictional heroes, Michael Sims presents a fully documented and carefully researched study of Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930) and how he eventually achieved success as the author of the wildly popular Sherlock Holmes novels. Born in Scotland, Doyle, twenty-seven years old, was working full-time as a physician in Portsmouth, England when he started working on his first novel, A Study in Scarlet. He had always admired how his favorite teacher in medical school, Dr. Joseph Bell, was able to tell unfathomable amounts of information about his patients by paying attention to the tiniest of details – observations about their physical condition, appearance, past history, and reasons for seeking medical help. The personal physician to Queen Victoria whenever she visited Edinburgh, Bell was widely respected throughout the city, and Doyle believed that Bell’s observant and effective approach to patients would greatly improve detective stories if those methods were used by detective heroes.

Written as a biography, not of Arthur Conan Doyle’s life but of the specific influences on his life which led to his successful creation of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson as fictional heroes, Michael Sims presents a fully documented and carefully researched study of Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930) and how he eventually achieved success as the author of the wildly popular Sherlock Holmes novels. Born in Scotland, Doyle, twenty-seven years old, was working full-time as a physician in Portsmouth, England when he started working on his first novel, A Study in Scarlet. He had always admired how his favorite teacher in medical school, Dr. Joseph Bell, was able to tell unfathomable amounts of information about his patients by paying attention to the tiniest of details – observations about their physical condition, appearance, past history, and reasons for seeking medical help. The personal physician to Queen Victoria whenever she visited Edinburgh, Bell was widely respected throughout the city, and Doyle believed that Bell’s observant and effective approach to patients would greatly improve detective stories if those methods were used by detective heroes.

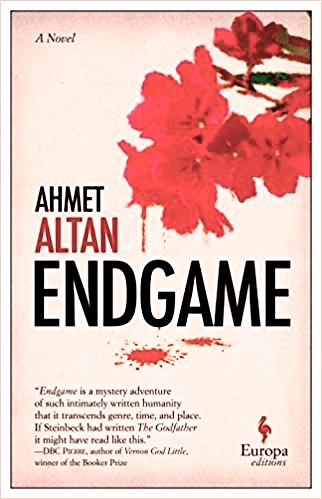

In his first novel to be translated into English, author/journalist Ahmet Altan sets his novel in a small, unnamed town in rural Turkey to which an unnamed Turkish author has gone to retire and work on a new book. In the first two pages of this book, however, the reader learns that that author has committed a murder, though the victim is also unnamed. What follows is a novel which is both clever and exasperating, as the main character inserts himself into the life of a small town with long-standing rivalries and intrigues and becomes, himself, a part of the frenzied action and reaction to slights and betrayals, both real and imagined. As the novel opens, the author is sitting outside, apparently in the final hours of his life, waiting to be apprehended for murdering a resident and contemplating the meaning of life and his responsibility for his own actions – an irony, since he also believes his predicament to be “God’s work.” God, after all, “has a savage sense of humour. And coincidence is his favorite joke.”

In his first novel to be translated into English, author/journalist Ahmet Altan sets his novel in a small, unnamed town in rural Turkey to which an unnamed Turkish author has gone to retire and work on a new book. In the first two pages of this book, however, the reader learns that that author has committed a murder, though the victim is also unnamed. What follows is a novel which is both clever and exasperating, as the main character inserts himself into the life of a small town with long-standing rivalries and intrigues and becomes, himself, a part of the frenzied action and reaction to slights and betrayals, both real and imagined. As the novel opens, the author is sitting outside, apparently in the final hours of his life, waiting to be apprehended for murdering a resident and contemplating the meaning of life and his responsibility for his own actions – an irony, since he also believes his predicament to be “God’s work.” God, after all, “has a savage sense of humour. And coincidence is his favorite joke.”

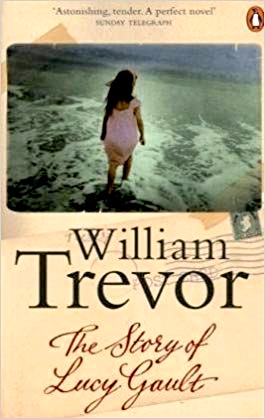

This old-fashioned saga of eighty years in a family’s life, from the Partition of Ireland in 1921 to the present, differs from other such novels in that it is very short, a mere 228 pages, packed with intimate character portrayals and enough heartache to fill a book three times its size. Like many other authors who excel at short story writing, Trevor compresses images and scenes, and his well honed ability to make a few words do the work of dozens allows him to create a book which is simultaneously intensely personal and broad in its time horizon.

This old-fashioned saga of eighty years in a family’s life, from the Partition of Ireland in 1921 to the present, differs from other such novels in that it is very short, a mere 228 pages, packed with intimate character portrayals and enough heartache to fill a book three times its size. Like many other authors who excel at short story writing, Trevor compresses images and scenes, and his well honed ability to make a few words do the work of dozens allows him to create a book which is simultaneously intensely personal and broad in its time horizon.