“The chessboard has been my means of artistic expression: the canvas on which I painted, my musician’s staff, the blank page for my poetry. My devotion has been such that I have been compelled to play even in the most abject conditions. While bedridden due to illness, I kept myself alive by re-creating entire games in my mind. I have played in the darkness of a cell, I have played while hungry and cold…[and even] on the eve of being sent before a firing squad. Chess has been the star that guided me…”—Alexandre Alekhine, chess champion of the world.

On March 24, 1946, fifty-four-year-old world chess champion Alexandre Alekhine* was found dead in his hotel room at the famed Hotel do Parque in Estoril, Portugal. He had been living there for two months during the off-season, first awaiting news of a worthy opponent and then awaiting the details regarding a future match. As Italian author Paolo Maurensig develops this story, Alekhine’s life in several different countries under several different governments begins to unfold, and the suspicious circumstances in which his body was found lead to the inescapable conclusion that this death may not have been an accident. Alekhine was fully dressed and wearing a heavy coat as he sat in his overheated room, apparently eating a meal, though he had already attended a full dinner in his honor that same night. The journalist who reported on his death in the Portuguese press, Artur Portela, did so in the face of strong censorship and the influence of the secret police of the long-time ruler of Portugal, Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, which promptly ended the investigation, making no comment at all. This led some to wonder about the possible involvement of the Portuguese in Alekhine’s death. Others pushed the idea that his death was suicide.

On March 24, 1946, fifty-four-year-old world chess champion Alexandre Alekhine* was found dead in his hotel room at the famed Hotel do Parque in Estoril, Portugal. He had been living there for two months during the off-season, first awaiting news of a worthy opponent and then awaiting the details regarding a future match. As Italian author Paolo Maurensig develops this story, Alekhine’s life in several different countries under several different governments begins to unfold, and the suspicious circumstances in which his body was found lead to the inescapable conclusion that this death may not have been an accident. Alekhine was fully dressed and wearing a heavy coat as he sat in his overheated room, apparently eating a meal, though he had already attended a full dinner in his honor that same night. The journalist who reported on his death in the Portuguese press, Artur Portela, did so in the face of strong censorship and the influence of the secret police of the long-time ruler of Portugal, Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, which promptly ended the investigation, making no comment at all. This led some to wonder about the possible involvement of the Portuguese in Alekhine’s death. Others pushed the idea that his death was suicide.

Portela’s reports on some of the inconsistencies regarding Alekhine’s death and the gossip surrounding it suggest that the death might have been part of an international conspiracy. The Russians, under whose aegis Alekhine had lived as a child and young man, were furious at the negative public comments he had made about “new” Russian chess strategies and moves which had changed the nature of the chess game, as exemplified by the newest Soviet chess stars, and the Russians were unsure of whether they wanted to continue to take credit for his world-wide success or take organized action against him and his career. The French considered Alekhine a collaborator for his actions during the German Occupation. The Nazis, who had ruled occupied France while Alekhine lived there, exercised control over him in the aftermath by threatening to release and use statements of his anti-Semitism, which he claimed that he had made under duress in order to play chess. The White Russians would not forgive him because he had worked during the Revolution with the ministry which appropriated the assets of those Russians who had emigrated. Even his four ex-wives and his alienated children had given up on him. In short, he had no friends, lived only to play chess, and considered his work on strategies to be an art form, rather than a series of mathematical actions and reactions.

Hotel do Parque in Estoril, Portugal, where Alekhine stayed as the only guest for the month of January, 1946.

Even his first month in Estoril, totally alone as the hotel’s only guest, offered no relaxation. He stayed up all night, ate raw meat while studying chess moves, and occasionally walked to the lighthouse or the beach. He was so short of cash that he was unable to play in a London tournament, and he had to cut down on his drinking and reduce his cigarette consumption to “only” forty cigarettes a day. His doctor had said that his liver was in such bad shape that he might last only a year if he did not change his habits. When he hears violin music coming from the room next door, he reaches out to befriend the musician, David Newmann, who will be playing at the Lisbon Philharmonic the following week. He also meets a new couple at dinner, Jorge Correira and his wife. While he is anxious to hike with the musician Neumann along the water, he recognizes a note of falsity in Jorge Correira’s questions in the dining room and wonders why Correira is so interested in his past. He wonders if Correira might have been the person who left a packet of disturbing newspaper articles and photographs outside his door. The photographs of Nazis at the Nuremberg Trials include one person who had been the Reichminister of Poland, someone with whom Alekhine and his then-wife had visited.

In one revealing personal reminiscence, Alekhine relates how chess saved him from imminent execution, though it led to the death of his brother. As the book continues, however, it loses its momentum, to some extent, with pages devoted to his marriages, which are not relevant to the action; philosophical passages in which the mysterious Correira lectures ominously about the nature of good and evil and free will; some blatantly anti-Semitic commentary by various characters; and observations about several secret service agencies and spies from different countries who are hiding both inside and outside Alekhine’s hotel. While these may add to the atmosphere and illustrate some of the deadly rivalries among different political movements and Alekhine’s relationship with them, they do not advance the narrative. Part of the problem here is that the author, Maurensig, is not able to find enough new information about Alekhine to bring this unlikeable man to life in any sort of sympathetic way. Alekhine has done whatever is most expedient on every occasion in which he has had to make a choice, playing his life as if it is a chess game in which making certain sacrifices will let him win at great cost, but win, nevertheless – his primary goal.

The last twenty pages, “The Final Secret,” return the novel to the narrator/author as he explains some final information which he has received many years later from a former war correspondent, now an old man, about the discovery of Alekhine’s body, the “testimony” of a former member of Salazar’s secret police regarding what the body looked like, and an exhumation. Whether any or none of these statements are real is uncertain. What is certain is that Maurensig did manage to keep this reader, who is not a chess fanatic, engaged and interested in a book in which the main character is unlikeable; lives in a complicated political milieu in which he treats life and people dispassionately – as if they are all simply a part of his own game of life; and remains at the end of the novel as much of a mystery as he was at the beginning, and he does this within a novel in which every main character is male, a fact which is so unusual these days that it is notable.

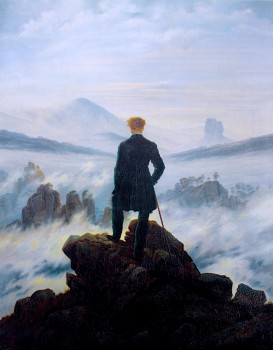

“Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog” by Caspar David Friederich, 1818, is a painting which Alekhine remembers in a poignant moment as he is walking with Neumann, who is ahead of him, one of the few emotional moments we see from Alekhine in this novel. Click to enlarge.

*Note: To be consistent with the book, I am using the spelling of “Alexandre,” instead of “Alexander,” the English spelling.

ALSO reviewed here: A DEVIL COMES TO TOWN and GAME OF THE GODS

Photos: The author’s photo is found on https://www.goodreads.com/

The postcard of Portugal’s venerable Hotel do Parque is from https://arquivodigital.cascais.pt

Alexandre Alekhine, world chess champion, is the subject of a well researched bio on Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/

Included in the Wikipedia bio of Alekhine, is this picture of Alekhine defending his world chess championship in 1934. https://en.wikipedia.org/

As Neumann is walking with Alekhine along the cliff beach, he sees him as a real friend, one of his only friends, a memorable, poignant moment for him, which reminds him of the 1818 Caspar David Friederick painting, “Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog.” https://literarylife.org/