“Most people are blown away by their first sight of the Grand Canyon; their first experience of the Balinese Monkdu Dance, the Ketjak; their first glimpse of a breaching humpback whale. That was how I felt. Being among these [Ju/’hoansi, the Real People of Namibia] exceeded my dream. And maybe happiness was the wrong word; perhaps what I felt was bliss bordering on rapture.”

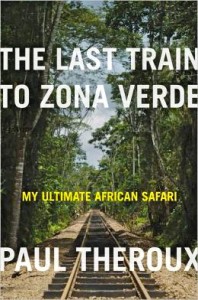

If a reader were to base his/her whole opinion of Paul Theroux’s latest travel book on this one quotation from the opening chapter, one might conclude that this book is a genuflection to simpler cultures living the hunter-gatherer lives of their forbears, a rare reaction by Theroux who is notoriously hard to please. That conclusion would be completely wrong, however, even in relation to his experience among the lovely Ju/’hoansi bush people who so impress him in Namibia. Traveling to places rarely, if ever, visited by tourists – this time to places along the south and west coasts of Africa – Theroux flashes back to the beginning of his trip in South Africa, where he spends significant time in the townships of Capetown. There he discovers that while these special townships created for the poor have improved in the last ten years, more desperate poor are arriving from rural areas and creating new, and even more primitive settlements in slums on the outskirts. He is ready, perhaps even over-anxious, for the surprise of the Ju/’koansi group when he explores Namibia.

If a reader were to base his/her whole opinion of Paul Theroux’s latest travel book on this one quotation from the opening chapter, one might conclude that this book is a genuflection to simpler cultures living the hunter-gatherer lives of their forbears, a rare reaction by Theroux who is notoriously hard to please. That conclusion would be completely wrong, however, even in relation to his experience among the lovely Ju/’hoansi bush people who so impress him in Namibia. Traveling to places rarely, if ever, visited by tourists – this time to places along the south and west coasts of Africa – Theroux flashes back to the beginning of his trip in South Africa, where he spends significant time in the townships of Capetown. There he discovers that while these special townships created for the poor have improved in the last ten years, more desperate poor are arriving from rural areas and creating new, and even more primitive settlements in slums on the outskirts. He is ready, perhaps even over-anxious, for the surprise of the Ju/’koansi group when he explores Namibia.

On his loosely planned itinerary, he expects to travel up the west coast, primarily by train and bus, from Capetown to Timbuktu in Mali. He has set no time limits and made no advance reservations, and he will do what he has always done – seize opportunities as he travels, make notes as he goes, and post his observations of this part of Africa in ways similar to his observations of Africa’s eastern coast ten years ago. His visit with the Ju/’koansi in Namibia has been the first sign of hope that he has had on this trip since he started in Capetown.

On his loosely planned itinerary, he expects to travel up the west coast, primarily by train and bus, from Capetown to Timbuktu in Mali. He has set no time limits and made no advance reservations, and he will do what he has always done – seize opportunities as he travels, make notes as he goes, and post his observations of this part of Africa in ways similar to his observations of Africa’s eastern coast ten years ago. His visit with the Ju/’koansi in Namibia has been the first sign of hope that he has had on this trip since he started in Capetown.

In Theroux’s previous book, Dark Star Safari (2004), he details his travels from Egypt to Capetown, and though he makes insightful comments on the countries he visits, he is dispirited by what he sees on that trip, both in terms of governments and in terms of the daily lives of ordinary citizens. Even hungrier and more impoverished in 2004 than they were in 1963, when he was a Peace Corp volunteer in Malawi, and with even fewer resources, the rural poor and the urban slum-dwellers whom Theroux meets leave him both sad and angry, and he is a curmudgeonly (and seemingly arrogant) narrator to spend time with for the nearly five hundred pages of that book.

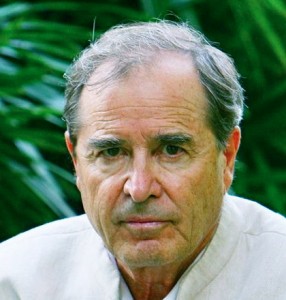

This new book shows even more poverty and economic horror, but Theroux himself is a much more thoughtful and sensitive narrator here, and as he makes sometimes risky trips into rarely visited areas, teaches a few English classes, and meets and admires a number of people dedicated to improving lives, he inspires the same admiration for them in the readers of this book as he obviously experiences himself. Theroux also reveals his own fears and insecurities, something I have never seen him do in any of his previous books. Now seventy-two, he knows that this may be the last such trip for him. Though he has seen and done a lot in his life, he no longer feels as if he has to test himself, and his conclusions are bittersweet for those of us who have followed his work since the 1960s. He becomes more “human,” more one of “us” than I have seen before.

In Capetown, he notes that on Table Mountain, the rich look down on the poor, physically, from the mountain, and the poor must look up at the rich. No one can hide. Life for the poor has improved, though Theroux decries the “township tours,” run by tour companies, which now take tourists through poor townships in a program to show all aspects of South African life – “the voyeurism of poverty,” in Theroux’s opinion. He also points out the crime statistics. Since the end of apartheid in 1994, three thousand white settlers have been murdered, and he criticizes entertainers like Bono for their lack of statistics as they make proclamations to the world.

Windhoek in Namibia provides a huge change from the grinding poverty and filth of South Africa’s townships and slums. A city founded by German colonizers, it is clean, with people sweeping the streets, which are almost absent of trash. Here he expounds on his ideas regarding aid, which he sees as well-intentioned, though promoting dependency and corruption, and impeding growth. With its high literacy rate, he says, Namibia has more high school graduates than Newark, NJ, despite Namibia’s long war with S. Africa, and there are fewer murders. The culture as he sees it in Windhoek, is characterized by “efficiency, order, mildness, and cleanliness.” Tsumkwe, a rural crossroads in Namibia, is, however, “a famine-haunted, thinly populated bush area, near the Angola border. There he meets the Ju/’hoansi and officials from UNESCO, from whom he learns more about the Ju/’hoansi. Ultimately, he realizes that his initial impression was wrong: These are the “most victimized and brutalized people in the bloody history of southern Africa…They are reminders of who we once were, our ancient better selves.”

Abu Camp in Botswana, in which orphaned and injured elephants are trained to carry tourists through the Ojavango Delta (since they cannot yet be returned to the wild) introduces Theroux to young people who are devoted to their jobs of training these elephants to carry people on rides through the Delta. Wealthy tourists spend thousands of dollars to come to this camp and do their tour on the backs of elephants, an activity that is not natural for this variety of elephant. The contrasts between these tourists and the poor local people who live in rural areas are highlighted when some young people wait till tourists finish their meals and then ask politely if they can eat what is left on their plates.

The newly built train and rail station in Lobito, Angola, opened by the Chinese government in August, 2012

Angola, Theroux’s next stop, proves to be the turning point. One of the richest countries in the world in terms of its oil production and revenues, all of which end up in the pockets of politicians and businessmen, and none of which trickles down at all, Angola becomes the centerpiece of the book in terms of the corruption at the heart of African life. No animals or birds at all exist in the wild here, thanks to years of bloody wars and the millions of land mines that prevent humans and animals from moving freely. Angola generates “a billion dollars of gross revenue every five days, an almost unimaginable cash flow, with none going to the people.” As one man comments, “This is what the world will look like when it ends.”

Giant sable antelope, the only such animal left in Angola, with horns measuring five feet in length.

Ultimately, Theroux must decide whether to continue on to a tiny area of Angola, an “island” completely surrounded by the Congo, in order to see the rare sable antelope, with the longest horns of any antelope in the world. It is now the only such animal left in what is officially Angola, and it survives because it lives in a protected habitat. Ultimately Theroux asks, “What had I learned?” And then answers: “Proctology pretty much describes the experience of traveling from one African city to another, especially the [horrific] cities of urbanized West Africa…[One needs] a strong stomach and a fascination with decay, and disorder, and hopelessness, and township anarchy.” As Theroux completes his journey, he reveals his own melancholy and even despair, feelings which the reader shares with him.

ALSO by Theroux: SIR VIDIA’S SHADOW, about his relationship with Nobel Prize-winner V. S. Naipaul in Uganda, and DARK STAR SAFARI

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Yingyong Un-Anongrak, appears on http://travel.nationalgeographic.com

The map of the area is from http://www.sitesatlas.com/. Just double-click on the image to go to a larger copy of this map.

Table Mountain, one of the Seven New Wonders of Nature, is here: http://www.tandatula.com/

An article about the Ju/’hoansi (and additional photographs) may be found on http://www.wilkinsonsworld.com/, the site of this photo.

Abu Camp on the Okavango Delta may be found here:

http://www.smithsonianmag.com. Photo by Sergio Pitamitz / Biosphoto / Minden Pictures

The Lobito Railway Station appears here: http://www.angolahub.com

The giant sable antelope with its five-foot horns is an exhibit in the American Museum of Natural History: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Photo by Stavenn.