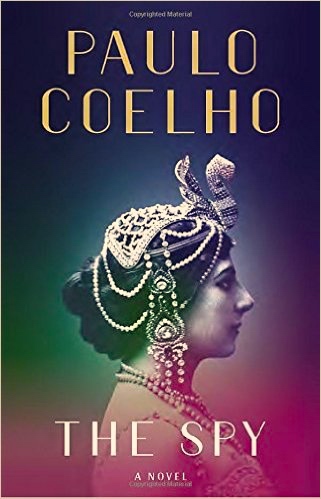

Note: Brazilian author Paulo Coelho has sold more than two hundred million books worldwide. Published in eighty-one languages, he is, according to his publisher, “the most translated living author in the world.”

“There was never any concrete evidence against me – only documents that had been tampered with – but you will never publicly admit that you allowed an innocent woman to die. Innocent? Perhaps that is not the right word. I was never innocent, [but] I thought I could manipulate those who wanted state secrets…In the end, I was the one manipulated…convicted of espionage even though the only thing concrete I traded was the gossip from high-society salons…I never revealed anything new.” –Mata Hari to her lawyer, M. Clunet.

One of t he legends of World War I, Mata Hari has been, for over a hundred years, a symbol of mystery, excitement, and danger. Her exotic life and her eventual fate – an early morning execution by a firing squad of French soldiers on October 15, 1917 – has always felt somehow “deserved” by a woman who so craved attention that she publicly flouted every norm of society in order to develop a reputation as an erotic dancer and lover, and who was eventually declared a spy by the French government. Fearless in her private life and pragmatic enough to realize, as she was approaching age forty, that she was not as supple – or as slim – as she once had been, she eventually accepted a six month contract to perform in Berlin in 1916, seeing this change of location as an opportunity for new rewards and wider opportunities. The big question raised by this novel is whether her various liaisons in Germany and France provided her with opportunities to share real secrets or whether she was merely a scapegoat, conveying the society gossip of the day, as she has claimed. When she left Germany precipitously in an attempt to return to Paris in 1917, the French declared her a German spy trying to re-enter. Whether this is true has never been fully answered.

he legends of World War I, Mata Hari has been, for over a hundred years, a symbol of mystery, excitement, and danger. Her exotic life and her eventual fate – an early morning execution by a firing squad of French soldiers on October 15, 1917 – has always felt somehow “deserved” by a woman who so craved attention that she publicly flouted every norm of society in order to develop a reputation as an erotic dancer and lover, and who was eventually declared a spy by the French government. Fearless in her private life and pragmatic enough to realize, as she was approaching age forty, that she was not as supple – or as slim – as she once had been, she eventually accepted a six month contract to perform in Berlin in 1916, seeing this change of location as an opportunity for new rewards and wider opportunities. The big question raised by this novel is whether her various liaisons in Germany and France provided her with opportunities to share real secrets or whether she was merely a scapegoat, conveying the society gossip of the day, as she has claimed. When she left Germany precipitously in an attempt to return to Paris in 1917, the French declared her a German spy trying to re-enter. Whether this is true has never been fully answered.

Author Paulo Coelho gives life to her story by dividing his novel into three parts, and though each part deals with a different aspect of Mata Hari’s earlier life, each also provides her commentary on her current conditions as a prisoner. Jumping around in time, the opening Prologue begins with the execution of Mata Hari, on October 15, 1917, vibrantly conveying the thinking of this woman, an entertainer with a reputation to “protect,” at the same time that it also illustrates her incredulity that she has not been pardoned, as she has expected. For the week before her execution, she writes her memoirs for her daughter, back in her native Holland, so that her daughter will know something about her mother. Part I, which follows, tells of her early life as Margaretha Zelle, a Dutch schoolgirl, her marriage to an abusive, older husband when she is eighteen, her move to Java and her later return to Holland, and her eventual decision to abandon Holland secretly and head to Paris alone.

Author Paulo Coelho gives life to her story by dividing his novel into three parts, and though each part deals with a different aspect of Mata Hari’s earlier life, each also provides her commentary on her current conditions as a prisoner. Jumping around in time, the opening Prologue begins with the execution of Mata Hari, on October 15, 1917, vibrantly conveying the thinking of this woman, an entertainer with a reputation to “protect,” at the same time that it also illustrates her incredulity that she has not been pardoned, as she has expected. For the week before her execution, she writes her memoirs for her daughter, back in her native Holland, so that her daughter will know something about her mother. Part I, which follows, tells of her early life as Margaretha Zelle, a Dutch schoolgirl, her marriage to an abusive, older husband when she is eighteen, her move to Java and her later return to Holland, and her eventual decision to abandon Holland secretly and head to Paris alone.

Part II recreates the excitement she generates as a “Javanese dancer” with an exotic, Eastern background, as she performs in Paris for people who believe that she is a genuine native of the Dutch East Indies. Guided by Emile Guimet, the founder of the Musee Guimet, she raises her “traditional” dancing to an art form at a time in which Salome’s Dance of the Seven Veils is also becoming a hit in Paris. She meets and bewitches artists like Picasso and Modigliani, and seduces a large number of aristocrats and patrons. Part III, by contrast, is her final commentary on her life and trial, her belief that she has had the wrong lawyer to defend her, and her unyielding conviction that there cannot be anything in her dossier that could possibly be incriminating and that she will therefore be exonerated. As she readies herself for her execution, she betrays no nervousness, behaving as if she is getting ready for the most important party of her life.

Within this unusual framework – and a conclusion known from the first page – author Coelho manages to keep the reader curious about the most important aspects of Mata Hari’s life and eventual death. Few readers will claim that they come to know Mata Hari here, as she greatly values her independence and trusts no one. Ironically, the person with whom she makes one of the few connections in her life is the wife of her patron, Monsieur Guimet, who gives her early advice: “Never fall in love. Love is a poison…Love sweeps everything you are from the face of the earth and in its place leaves only what your beloved wants you to be.” But Mata Hari is relatively discreet in her sexual behavior, and she tends to regard her affairs as a duty unrelated to her feelings. Mme. Guimet’s second piece of advice is simply that “Life is very complicated. What’s simple is wanting an ice cream [or] a doll, [winning] a game..[or] wanting to be famous, but staying that way for more than a month or a year, especially when that fame is linked to one’s body, is what is hard.” Mata Hari, always pragmatic, understands, as she ages, that her opportunities are becoming more limited, a factor in her acceptance of the contract in Berlin when she is nearly forty and unable to find work in Paris.

On her way to Germany by train, she has a chance to evaluate her life at this turning point, seeing herself as completely different from all the other women in that train car: “I was an exotic bird traversing an earth ravaged by humanity’s poverty of spirit. I was a swan among ducks who refused to grow up, fearing the unknown.” As she looks at the man accompanying her to Berlin, she realizes, however, that “I was under his control, he no longer had to answer anything. [What] I had to do was dance and dance, even if I was no longer as flexible as I was before.” She knows she can always use the same trick she used when first arriving in Paris, “Show them something exotic…and the [audience], always eager for something new, will certainly believe it,” at least for a little while. Ambitious and hard-working, in her way, Mata Hari also acts without much thought, and that ignorance may have been her undoing. The Epilogue, which details the aftereffects of Mata Hari’s execution, deserves careful reading, and it is stunning in its revelations about her accuser, the French prosecutor, the government with its censorship, and the “deductions, extrapolations, and assumptions” made during the proceedings which affected the trial’s outcome. This reader, at least, will no longer regard “Mata Hari” as a “femme fatale” whose life’s outcome came about as a result of her own choices.

On her way to Germany by train, she has a chance to evaluate her life at this turning point, seeing herself as completely different from all the other women in that train car: “I was an exotic bird traversing an earth ravaged by humanity’s poverty of spirit. I was a swan among ducks who refused to grow up, fearing the unknown.” As she looks at the man accompanying her to Berlin, she realizes, however, that “I was under his control, he no longer had to answer anything. [What] I had to do was dance and dance, even if I was no longer as flexible as I was before.” She knows she can always use the same trick she used when first arriving in Paris, “Show them something exotic…and the [audience], always eager for something new, will certainly believe it,” at least for a little while. Ambitious and hard-working, in her way, Mata Hari also acts without much thought, and that ignorance may have been her undoing. The Epilogue, which details the aftereffects of Mata Hari’s execution, deserves careful reading, and it is stunning in its revelations about her accuser, the French prosecutor, the government with its censorship, and the “deductions, extrapolations, and assumptions” made during the proceedings which affected the trial’s outcome. This reader, at least, will no longer regard “Mata Hari” as a “femme fatale” whose life’s outcome came about as a result of her own choices.

Wearing a long, fur-trimmed coat and a large hat to hide her tousled hair, Mata Hari faces her executioners. Her hands are not tied, and she does not wear a blindfold. Two nuns and a priest are on the far right of this photo.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from https://continuousreader.blogspot.com

Mata Hari dances Salome’s Dance of the Seven Veils: http://www.radikal.com

Mata Hari as a “lady,” dressed for an evening with elegant friends: http://www.biography.com

News of Mata Hari’s execution: http://milhomme.blogspot.com

Photo of the execution by firing squad: Mata Hari dresses in a fur-trimmed coat and wears a large hat to hide her tousled hair. She is not blindfolded, at her own request, and her hands are not tied. http://margaretperry.org/