Note: Peter Carey is only the second author (along with J. M. Coetzee) to have twice been WINNER of the Booker Prize.

“Anyone who has ever observed a successful automaton, seen its uncanny lifelike movements, confronted its mechanical eyes, any human animal remembers that particular fear, that confusion about what is alive and what cannot be born. Descartes said that animals were automata. I [believe] it was the threat of torture that stopped him saying the same about human beings.”

Although he has often dealt with the themes of identity, reality, and what it means to be human, Australian author Peter Carey creates a whole new approach to these ideas in this complex and sometimes strange novel with two overlapping narratives set one hundred fifty years apart. Catherine Gehrig, a Curator of Horology (clockwork) at the Swinburne Museum in London, has led a secret life for thirteen years, enjoying an affair with Matthew Tindall, the married Head Curator of Metals. On April 21, 2010, she arrives at work to discover that Matthew is dead, and that she is apparently the last to know. Frantic with grief which she dare not show at the office, she cannot even imagine how to go on with her life without Matthew. “Light the leaves and pyre wood,” she thinks, “because nothing could hurt more than this.”

Although he has often dealt with the themes of identity, reality, and what it means to be human, Australian author Peter Carey creates a whole new approach to these ideas in this complex and sometimes strange novel with two overlapping narratives set one hundred fifty years apart. Catherine Gehrig, a Curator of Horology (clockwork) at the Swinburne Museum in London, has led a secret life for thirteen years, enjoying an affair with Matthew Tindall, the married Head Curator of Metals. On April 21, 2010, she arrives at work to discover that Matthew is dead, and that she is apparently the last to know. Frantic with grief which she dare not show at the office, she cannot even imagine how to go on with her life without Matthew. “Light the leaves and pyre wood,” she thinks, “because nothing could hurt more than this.”

Catherine is so distraught that Head Curator of Horology, Eric Croft, whose specialty is restoring mechanical “singsongs,” takes dramatic action. He arranges for her to take sick leave and then to move to the privacy of the museum’s Annexe in Olympia, where she will have a special job – to go through eight boxes the size of tea chests, filled with assorted gears, screws, and machine parts,  along with assorted papers, associated with an automaton of a duck from the mid-1850s. The Swinburne specializes in “mechanicals” like this, and Carey’s descriptions of these creations are stunning. Croft’s “singsongs,” usually very elaborate, jeweled creations with many moving parts, were collected by the very wealthy in the mid nineteenth century; the automaton which Catherine will work to restore is simpler, though it still has over four hundred parts – a duck which moves, eats, and defecates.

along with assorted papers, associated with an automaton of a duck from the mid-1850s. The Swinburne specializes in “mechanicals” like this, and Carey’s descriptions of these creations are stunning. Croft’s “singsongs,” usually very elaborate, jeweled creations with many moving parts, were collected by the very wealthy in the mid nineteenth century; the automaton which Catherine will work to restore is simpler, though it still has over four hundred parts – a duck which moves, eats, and defecates.

When Catherine discovers notebooks that accompany the boxes, she quickly becomes absorbed in the story of how the duck came to be made, thereby introducing the second narrative, a detailed diary which opens in June, 1854, and features a style of writing compatible with the period. Henry Brandling, a wealthy Englishman with an invalid son believes that if he can find someone to make an amusing duck automaton, which will be based on the real plans for Vaucanson’s duck, made in the eighteenth century, that Percy will be filled with “magnetic agitation,” which will help him conquer his disease. He travels to Germany to Schwarzwald to find a clockmaker who will make the automaton, promising Percy that he will return by Christmas.

This singsong, like those which Erich Croft, Head Curator in this novel, worked on, was owned by Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild.

The desperate Catherine, whose alcohol and cocaine consumption is out of control, soon becomes totally engaged with Brandling’s notes and in her task regarding the restoration of the duck. Henry Brandling, in his narrative, is just as desperate to have the duck finished, even when the two artists he hires soon abandon Brandling’s plans and decide to make their own, much larger creation, a swan, which will cost more money and bring a higher fee.

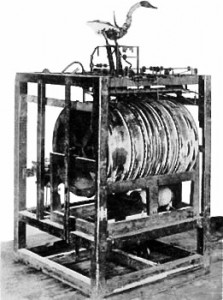

The original Vaucanson duck no longer exists, but it was recreated in the 19th century from descriptions left by the maker.

Within this unique and fascinating framework, Carey explores the many different aspects of reality and what makes humans unique. Automatons seem real, and the more complex the machinery is, the more “real” they seem, ironically. Henry Brandling’s efforts to get the automaton made also involve questions of reality. He does not know if the people he has hired are being honest with him and whether he will ever actually see the toy he has already paid for. Sumper, the man who is ultimately in charge of the task, meets Brandling at the inn the night he arrives, but he already knows who he is and why Brandling is there, adding an element of mystery and otherworldliness to what has seemed so far a fairly straightforward tale. Monsieur Arnaud, who works with Sumper, collects fairy tales, and the maid in Brandling’s inn and her delightful, lame son, all seem to possess unusual powers, or at least powers that Brandling does not fully understand. Catherine’s view of her own reality also changes as the restoration work continues, especially when her assistant makes suggestions that something otherworldly is hidden within the partially restored hull.

This still photo of an automaton swan matches in all details the description of a swan in Carey’s novel.

While all this is going on, other motifs arise and continue, and these are sometimes mystifying, since they do not feel completely integrated with the narrative. Sumper gives Brandling a playing card showing the “deep order” of the city of Karlsruhe, a sketch of the city arranged as a perfect circle, and references to this appear throughout the novel. Sumper has studied in England, and he expounds to his assistants about Sir Albert Cruickshank, a mathematician whose financing for the “Cruickshank engine,” a primitive adding machine and early computer, was halted by Queen Victoria. Sumper paraphrases Cruickshank in remarks he makes to Brandling, saying, “In this very room, you have been anointed as courier, and you will play your role never knowing what you have done…Those beings before you now…have a sphere of sensibility and intellect far superior to the inhabitants of this earth,” a passage which “spooks” Catherine when she reads it. Sumper has also made a satiric automaton of Jesus Christ for Cruickshank, to “lighten his heart” after the Queen gives away his “engine.” And while all this is being described, the BP gulf oil spill, which began the day that Matthew died, is introduced into Catherine’s world and parallels are drawn between it and the past: “Who made the machine that kills the ocean?” Fewer of these motifs would have strengthened the narrative and the themes, for this reader at least.

Great dialogue, fascinating subject matter, important themes treated in unique ways, and characters who engage our interest make this a story to celebrate. The narrative, though wildly creative, seems a bit strained to me, however, when all the peripheral elements and motifs are introduced as parallels and overlapping images. There is much to ponder here. Perhaps a bit too much.

ALSO by Peter Carey: THEFT, A LONG WAY FROM HOME

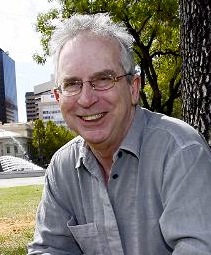

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Kelly Barnes, The Daily Telegraph, appears on: http://www.couriermail.com.au

This singsong, like those which Erich Croft, Head Curator in this novel, worked on, was owned by Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild. The emperor and four musicians move, and the jewel-encrusted flowers open and close. Made in London by Hubert Martinet, ca.1768 – 1772. http://collection.waddesdon.org.uk

The original Vaucanson duck no longer exists, but it was recreated in the 19th century from descriptions left by the maker. It required 400 moving parts to make the duck defecate (its primary charm, apparently). http://history-computer.com/Dreamers/Vaucanson.html

This still photo of an automaton swan matches in all details the description of a swan in Carey’s novel. (The YouTube video, above, shows how it works.) http://www.bowesmuseum.org.uk