“They’re elephant keepers. That’s Mother and Father’s problem. They’re elephant keepers without knowing it…They want to know what God really is; they want to meet God, and that is why it is so important to be sure He is in the sacraments…It is this yearning that has given them that sorrowful look around the eyes, and it is a yearning as big as an elephant, and we can see that it will never be fulfilled…We have seen their private elephant in its natural size.”

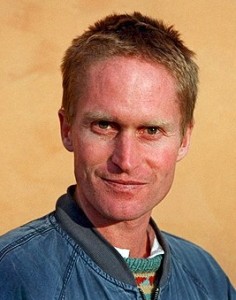

Danish author Peter Hoeg can never be accused of “writing the same book twice.” This one, like its predecessors, is completely different from all his other novels. Smilla’s Sense of Snow is an exotic thriller; Borderliners (my personal favorite) is a complex experimental novel of psychological suspense with a disturbed main character; The Woman and the Ape is an unusual love story which draws on the close genetic (and presumably emotional) connections between species; The Quiet Girl is a philosophical, impressionistic story in which a circus clown works with mysterious nuns to find some kidnapped children, their fates somehow connected to the science of sound.

Danish author Peter Hoeg can never be accused of “writing the same book twice.” This one, like its predecessors, is completely different from all his other novels. Smilla’s Sense of Snow is an exotic thriller; Borderliners (my personal favorite) is a complex experimental novel of psychological suspense with a disturbed main character; The Woman and the Ape is an unusual love story which draws on the close genetic (and presumably emotional) connections between species; The Quiet Girl is a philosophical, impressionistic story in which a circus clown works with mysterious nuns to find some kidnapped children, their fates somehow connected to the science of sound.

In The Elephant Keeper’s Children, Hoeg continues his focus on philosophy, this time dealing with the search for faith and meaning through an exploration of life and its parallel search for love and happiness – be it through Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, or Judaism. He does this, not as the main focus of the novel, but as part of the backstory involving three children who are searching for their mother and father, who have disappeared. Their father is the pastor of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Denmark on the island of Fino, where they all live, and their mother, the organist, is a mechanical genius with a gift for invention beyond what anyone in their congregation can imagine. The result is a farcical, picaresque story of c hases and escapes in which the fourteen-year-old main character (named Peter, in typically Hoeg fashion, suggesting issues the character might have in common with those of the author, on some level), along with his sixteen-year-old sister Tilde and terrier dog Basker, sets out to find their parents, sometimes aided by Hans, their older brother who is studying away from home. They know they must find their parents themselves before they are remanded to a children’s home by adults who seem to fear what they might do if left alone.

hases and escapes in which the fourteen-year-old main character (named Peter, in typically Hoeg fashion, suggesting issues the character might have in common with those of the author, on some level), along with his sixteen-year-old sister Tilde and terrier dog Basker, sets out to find their parents, sometimes aided by Hans, their older brother who is studying away from home. They know they must find their parents themselves before they are remanded to a children’s home by adults who seem to fear what they might do if left alone.

Along the way, they are aided or hindered by a wild assortment of characters with names reflecting the oddity of life on Fino: Bodil Hippopotamus, the municipal director of the commune where they live; Alexander Beastly Flounderblood, the new replacement for the headmaster at Peter’s school; Anaflabia Borderrud, the Bishop of Grena; and Leonora Ticklepalate, the head nun of a Buddhist community, computer genius, and counselor in a program that offers sexual-cultural coaching. Polly Pigonia heads the Hindu community and runs the main branch of Fino Bank, while Sinbad Al-Babblab is the imam of the Muslim community. Albert Winehappy, a man with many secrets, is believed to be an elephant keeper, and Pallas Athene runs an upscale brothel “themed on the Greek Mysteries” which services both men and women.

The children learn than their parents are not at La Gomera, a place they love in the Canary Islands.

All these characters will gather in Copenhagen where Sven Sewerman, a contractor who has renovated most of the sewers in Jutland, one of the wealthiest men on the island, is sponsoring a religious synod at a famous castle. In addition to the meetings of all the religious groups and an attempt to create peace among them, the synod will also involve a display of religious artifacts, including jewel-encrusted crucifixes. Four “floaters,” three men and one woman, may be terrorists planning havoc at the synod – unless they are stopped – and the issue of guns and explosives and who has them lurks as a threat as the plans for the synod progress.

As for where and how Peter and Tilde and Basker fit into all this craziness as they search for their parents…. The children have discovered some secret rooms and secret information in the elaborate rectory where they have lived with their parents, and as they investigate in an effort to find them, they begin to learn more about the past. Suddenly, they begin to question just why their parents have disappeared, remembering the last time they disappeared, and their eventual return home in a Maserati, with Mother wearing a mink coat. The children fear their parents have big plans for the synod.

A Maserati, similar to the one which the parents drove home from a previous "disappearance."

If all this sounds wild and wacky, it is. By far Hoeg’s lightest and most cartoon-like creation, the novel begs to be made into a slapstick comedy, the philosophical overlay seemingly imposed for “depth” and relevance. Issues of sex and computer encryption as an unusual path that leads “deep inside human beings” parallel the religious threads, and when Tilde herself is kidnapped, the plot, for all its wild forays into new directions, is brought to its conclusion, full of surprises. As time passes and lives change, Peter gradually matures during his “adventures,” and he eventually concludes that “the self is a room inside the prison, a room that will always be different from other rooms. For this reason the self will in some way always be alone, and always inside the building of which is it a part…As long as you’re a room, you’re imprisoned. But there’s a way out, and it’s not through a door, because no door exists to be open. All you have to do is see the opening.”

Tivoli Castle, Copenhagen

Hopeful and upbeat, this novel attempts to deal with big issues within a plot that never stops churning, the action progressing at warp speed throughout and sometimes leaving the reader breathless. The characters move too fast to allow for much contemplation of their inner characters, and the conclusion, which tries to bridge the gap between the wild ride of the action and the philosophical ideas which act as the anchor, feels contrived to make a statement. As the characters “go off into the sunset,” the reader may be left with some questions about how successfully the author has integrated their story with its thematic underpinnings, but happy to have taken this offbeat trip with him.

Also by Peter Hoeg: THE QUIET GIRL, THE WOMAN AND THE APE (on Amazon)

Photos, in order: The photo of the author by Janerik Henriksson appears on http://sverigesradio.se

La Gomera in the Canary Islands is shown here: http://oursurprisingworld.com

The Maserati photo may be found on http://www.caricos.com

Tivoli Castle in Copenhagen is from http://www.fanpop.com/

ARC: Other Press