Note: This novel was WINNER of The Commonwealth Writers Prize (UK) in 2010.

“Remembering has its own pleasure, like spreading wings. The mind unfurls and proclaims its own sensuality—and sometimes it does not matter if the memory is bleak.”

Usually when I re ad a novel described as “controversial,” I find myself seeing both sides of the controversy and writing about both sides when I write a review. With this novel, however, I was so exhilarated at the author’s bold originality, his ability to juggle his characters’ vibrant and creative inner lives while also examining the depressing circumstances under which they have lived, the sweeping historical scope which includes the entire twentieth century, and his total control of language with all its potential to amaze with its images and ideas, that this review will be, I hope, a celebration of one of the best and most innovative books I have read in a long time.

ad a novel described as “controversial,” I find myself seeing both sides of the controversy and writing about both sides when I write a review. With this novel, however, I was so exhilarated at the author’s bold originality, his ability to juggle his characters’ vibrant and creative inner lives while also examining the depressing circumstances under which they have lived, the sweeping historical scope which includes the entire twentieth century, and his total control of language with all its potential to amaze with its images and ideas, that this review will be, I hope, a celebration of one of the best and most innovative books I have read in a long time.

Daringly experimental, the book appears, superficially, to be two separate novels, but though it does fall into two parts, these two parts represent the two parts of our lives, the world of reality and the world of the imagination; here the events of the imaginative second part are a direct outcome of events from the first part, with clear parallels. As the main character remarks, “There is far more to  us than what we live…Life happens in a certain place for a certain time. But there is a great surplus left over, and where will we stow it but in our dreams?” Here author Rana Dasgupta shows that even a main character like this one, who appears to be a stodgy and uninteresting plodder, may have a vibrant fantasy world which keeps him alive when there is little else left in his world to provide inspiration and satisfaction.

us than what we live…Life happens in a certain place for a certain time. But there is a great surplus left over, and where will we stow it but in our dreams?” Here author Rana Dasgupta shows that even a main character like this one, who appears to be a stodgy and uninteresting plodder, may have a vibrant fantasy world which keeps him alive when there is little else left in his world to provide inspiration and satisfaction.

Ulrich, the Bulgarian main character, is almost a hundred years old as the novel opens. Blind, impoverished (after all the failed economic experiments of the various governments in Bulgaria), and alone, he spends his days looking out a window from which he cannot see anything, though he can hear the shouting and banging at the bus terminal outside his window and smell the fumes from the wall below him, which is used by “all the men who pass through the bus station.” His inner world, however, is lively and filled with events, real and imagined. “He knows that no living person is interested in his thoughts. But he has survived a long time, and he does not want to end with a mindless falling-off.”

Gradually, his past unfolds, and the reader comes to know the pivotal events in his life. A lover of music who had hoped to study violin, he switches to chemistry after his father angrily destroys his instrument, going to Berlin to study science until he runs out of money. There, however, he sees Albert Einstein, for whom he picks up some dropped papers, and is rewarded with the statement, “I am nothing without you,” a statement which haunts him till the end of his days. As a chemist, Ulrich dreams of someday finding something that will change the world forever. Only in his dreams is he able to be the musician that he believes himself to be at heart. Back home in Sofia, his best friend Boris exposes him to new ideas, as the post World War I political tumult unfolds. Boris, a talented violinist, is also a communist at a time when the fascists are vying for power. The fascist coup (1934) is superseded by the entrance of the Russians and their takeover of the government (1944). Ulrich eventually achieves a high position in the Kremikovtzi Steel Works, a company built by the Russians (1959) and which pollutes the land, rivers, and air for the rest of the century.

Gradually, his past unfolds, and the reader comes to know the pivotal events in his life. A lover of music who had hoped to study violin, he switches to chemistry after his father angrily destroys his instrument, going to Berlin to study science until he runs out of money. There, however, he sees Albert Einstein, for whom he picks up some dropped papers, and is rewarded with the statement, “I am nothing without you,” a statement which haunts him till the end of his days. As a chemist, Ulrich dreams of someday finding something that will change the world forever. Only in his dreams is he able to be the musician that he believes himself to be at heart. Back home in Sofia, his best friend Boris exposes him to new ideas, as the post World War I political tumult unfolds. Boris, a talented violinist, is also a communist at a time when the fascists are vying for power. The fascist coup (1934) is superseded by the entrance of the Russians and their takeover of the government (1944). Ulrich eventually achieves a high position in the Kremikovtzi Steel Works, a company built by the Russians (1959) and which pollutes the land, rivers, and air for the rest of the century.

When Ulrich is blinded in an experiment, he retires. Already nearly seventy, he remembers something Einstein said, when considering his own death, “I feel such solidarity with all things that it does not matter where the individual begins and ends.” Ulrich, too, senses an expanding of his spirit upon his retirement and the approach of his old age. “When his mind is particularly aware, Ulrich can sense the great black ocean of forgotten things, and, ignoring his beginning and end, he casts off into it. Everything he has known has drained, over time, from the actual world into this ocean, and he is blissful in the endless oblivion.”

Obviously, the plot described above is more philosophical and historical than it is psychological, emotional, or exciting. These pages, however, set up the second part of the novel, which begins at the halfway point of the book, the book of Ulrich’s memories and wild fantasies. Here a young man, Petar, much like Ulrich in size and personality, lives on a pig farm, where he eventually has a son named Boris. Boris, an instinctive musician, teaches himself to play the violin, learns from the gypsies, and enjoys his music. Succeeding chapters introduce other characters, such as Khatuna, a beautiful and very ambitious woman, and her sensitive poet brother, Irakli, who bring the country’s history and the collapse of communism up to date. Eventually, these two meet up with Boris, the violinist from the pig farm, and move from Tblisi to New York. The two artists, Boris and Irakli , are the vehicles through which the author comments on the art scene, its commercialization, and its parasites, like agent/manager Plastic Munari. Even the seemingly idyllic world of music and poetry has its down side.

, are the vehicles through which the author comments on the art scene, its commercialization, and its parasites, like agent/manager Plastic Munari. Even the seemingly idyllic world of music and poetry has its down side.

When Boris, “the son of [Ulrich’s] daydreams,” faces the death of a friend, Ulrich enters the story himself to offer advice. In a passage of extraordinary beauty and sensitivity, one of the high points of the novel for me, Ulrich says, “[Your friend] will find his way inside you, and you’ll carry him onward. Behind your heartbeat, you’ll hear another one, faint and out of step…Gradually, you’ll grow older than him, and love him as your son. You’ll live astride the line that separates life from death. You’ll become experienced in the wisdom of grief. You won’t wait until people die to grieve for them; you’ll give them their grief while they are still alive, for then judgment falls away, and there remains only the miracle of being.” A fine definition of love from a thoughtful and gifted author, not yet forty, in a book that I found riveting.

Photos, in order: The auth or’s photo is from his Amazon Author Page.

or’s photo is from his Amazon Author Page.

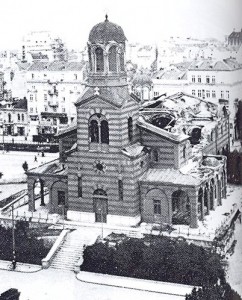

The self-portrait of Geo Milev, one of Ulrich’s friends, shows his expressionistic style. Milev, a communist who is a peripheral character here, was arrested and executed after the St. Nedelya bombing in 1925, which killed over a hundred high-ranking army members attending a funeral. His haircut hides his missing eye, lost fighting for his country in World War I. See http://en.wikipedia.org

The bombed out St. Nedelya Church, 1925: http://en.wikipedia.org

The Kremikovtzi Steel Works, built by the Soviets in 1959, where Ulrich works for many years. The works shut down some facilities and eventually closed in 2008, “because it did not have the raw materials needed to keep them going.” http://sofiaecho.com.

The final photo is of Bulgarian violin virtuoso Svetlin Russev, with his four-hundred-year-old violin. I imagine Boris as resembling him.: http://paper.standartnews.com