“Few people understand the delights of being like everyone else. For a pariah like me, it’s intoxicating. The pleasure of passing unobserved, of melting into the anonymous mass of those who have the right to carry on living. Of letting oneself be carried along with the flow. It’s as if one were suddenly accepted. Without displaying one’s condition. Without a sign on one’s chest saying PATIENT.”—Otto J. Steiner, Salzburg, 1940.

Otto J. Steiner, an Austrian whose diary from July, 1939, to August, 1940, forms the basis of this novel, is not talking here about any imminent danger he feels because he is of Jewish descent, and though he is aware that some Jews and gypsies have been “transferred,” he is puzzled about why: “What’s the connection between the Jews and the Gypsies? They have nothing in common. Apart from being wanderers.” Few people know of his Jewish background because he has never practiced any religion, and he is not really concerned much with politics. He is a “pariah” because he is dying of tuberculosis and is confined to a sanatorium, not allowed to mix with the general population unless he leaves under his own power for occasional walks. The immediate problems Steiner faces – isolation, declining finances, the delayed rent owed him by a young couple living in his apartment in Salzburg – complicate his life in the hospital by threatening his ability to remain in a single room, instead of a ward. His wife has died, and his sister living in Vienna is married to a “bourgeois and a snob” and does not communicate with him. His son has emigrated to Palestine. The only thing that keeps him going is his love of music, the recordings he has brought with him, his phonograph, and his desire to go “one last time” to the big Festspiele, which will be held in Salzburg in six months.

Otto J. Steiner, an Austrian whose diary from July, 1939, to August, 1940, forms the basis of this novel, is not talking here about any imminent danger he feels because he is of Jewish descent, and though he is aware that some Jews and gypsies have been “transferred,” he is puzzled about why: “What’s the connection between the Jews and the Gypsies? They have nothing in common. Apart from being wanderers.” Few people know of his Jewish background because he has never practiced any religion, and he is not really concerned much with politics. He is a “pariah” because he is dying of tuberculosis and is confined to a sanatorium, not allowed to mix with the general population unless he leaves under his own power for occasional walks. The immediate problems Steiner faces – isolation, declining finances, the delayed rent owed him by a young couple living in his apartment in Salzburg – complicate his life in the hospital by threatening his ability to remain in a single room, instead of a ward. His wife has died, and his sister living in Vienna is married to a “bourgeois and a snob” and does not communicate with him. His son has emigrated to Palestine. The only thing that keeps him going is his love of music, the recordings he has brought with him, his phonograph, and his desire to go “one last time” to the big Festspiele, which will be held in Salzburg in six months.

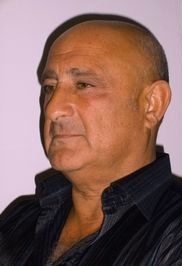

As author Raphael Jerusalmy develops Steiner’s story, he incorporates many details of Steiner’s daily life in the sanatorium – such as a meal of “boiled potatoes but no cod” – along with the variety of people who live and work there, all drawn together because of a terrible illness and not for political or religious reasons. Jerusalmy also uses Steiner’s personal isolation and his pre-occupation with his terminal illness to provide a new slant on events in Austria in 1939. By limiting Steiner’s “world” to the sanatorium, his illness, and his dedication to music, the author avoids repeating details (and clichés) so common to “Holocaust novels.” The author assumes that readers already know what happens when Jews and gypsies are “transferred,” and, just in case they don’t, he describes the tenant of Steiner’s apartment as an engineer on the railroad, working overtime transporting people from Salzburg to other places. The tenant is waiting for a new type of locomotive which will be more powerful and more efficient than the one he currently operates.

In February, 1940, Steiner is visited by his friend Hans, who, like Steiner, is a writer about music and a critic. Hans has been preparing the program for the next Festspiele, set to occur in Salzburg in late July, and the audience will consist primarily of Nazi officials and military. Hans has discovered that the entire music program, usually heavily Mozart (an Austrian), has been changed into a propaganda tool by the German occupiers, “an entertainment for the troops.” He wants Steiner to help him by writing the program notes, which the Nazis will review and/or edit, and Hans is afraid to do it. Steiner, however, is galvanized by this news: “Taking Mozart hostage. Demeaning him in that way…This farce must be stopped. At all costs. Mozart must be saved.”

Franz Lehar, one of four conductors for the Festspiele in 1940, arrives at the theater with his wife, who was Jewish before she converted to Catholicism when she married.

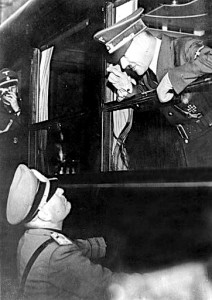

While Steiner and Hans are wrestling with issues of the coming music festival, the Nazi machine is on the move. News of the invasion of Poland in August, 1939, the call by Pope Pius XII for peace on Christmas Eve, 1939, an intensification of fighting on the Finnish front, and a raid on the sanatorium where Steiner is living, bring the outside world to Steiner and the patients, and when the anniversary of the Anschluss in March, 1940, is broadcast from Vienna, Steiner is appalled: “Deutschland uber alles echoed through the dayroom…Hymns and marches, oratorios, and masses. Why does all this have to happen to music? The instruments should fall silent. The tenors, the violinists. They shouldn’t be a party to all this. Out of a sense of decency.” A March, 1940, meeting between Hitler and Mussolini at the train station at the Brenner Pass gives hints of what will come with the Festspiele in Salzburg during the summer, and Steiner sees the new Petain government in France in July, 1940, as another betrayal: “We betray Mozart. [Petain] betrays Ravel and Debussy.”

As the journal of Steiner and his letters to his son prepare the reader (and the increasingly ill Steiner) for the dramatic climax planned for the Festspiele in July, author Jerusalmy also examines the changing conditions at the sanatorium, at which less and less food is available to the patients, wounded soldiers are replacing tubercular patients, and competition exists for medications.

Hitler has some final words with Mussolini before his train leaves the station at the Brenner Pass, where they met, 1940.

Saving Mozart is closer to a novella than to a novel, and though the author does include many details from the life of Steiner, and two long letters to his son to make the action come alive, some readers will still have a hard time identifying with Steiner. How does someone with a Jewish heritage, even one which he does not care to recognize publicly, ignore the actions of the Nazis on a daily basis and become incensed and galvanized only by the “insult” to the musical heritage of Mozart? And though the author works hard to present issues of the Holocaust from a new and different perspective, some readers will find the focus on a music festival and its selection of music in 1940 to be almost insignificant in scale when compared to the real-life “insults” to the Jewish populace of Austria during this same period. (If the author is being deliberately ironic here by focusing on a music festival to increase the reader’s horror at the Austrian populace’s lack of action in saving the Jews, that angle does not come through clearly. The book’s focus on Steiner and his music feels sincere.) Fast-paced and easy to read, the novel’s style has the clarity of young adult fiction, while evading the very real, very big, very human and social issues of the period. Mozart has survived, and the Festspiele has survived, with or without Steiner, and I suspect that a number of Jewish survivors of the Holocaust and their families may feel demeaned by this novel, considering the enormity of the horrors which took place in Austria while Steiner was so busy “saving Mozart.”

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://bbs.napolun.com/

Nazi flags line the approach to the theater where the Festspiele takes place. http://www.salzburgerfestspiele.at/

Franz Lehar was one of four conductors for the 1940 Festspiele, shown arriving at the theater with his wife. The others were Karl Bohm, who conducted on the last night of the festival, Hans Knappertsbusch, and Wilhelm Furtwängler. http://www.salzburgerfestspiele.at/

Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini meet at the Brenner Pass. They arrived by train from opposite directions and met on the platform between the two trains. http://bbs.napolun.com/

ARC: Europa Editions