Note: This novel was WINNER of the Man Booker Prize for 2014. Gould’s Book of Fish was WINNER of the 2002 Commonwealth Writers Prize, and Wanting (2008) was WINNER of the Queensland Premier’s Prize, the Western Australia Premier’s Prize, and the Tasmania Book Prize.

“To the railway, said Colonel Kona raising his teacup.

To Japan, said Nakamura, raising his cup in turn.

To the Emperor, said Colonel Kota.

To Basho! said Nakamura.”“They recited to each other more of their favorite haiku, and they were deeply moved not so much by the poetry as by their sensitivity to poetry; not so much by the genius of the poem as by their wisdom in understanding the poem; not in knowing the poem but in knowing the poem demonstrated the higher side of themselves and of the Japanese spirit…The Japanese spirit is now itself the railway [from Siam to Burma]…our narrow road to the deep north, helping to take the beauty and wisdom of Basho to the larger world.”

The “sensitivity” of these Japanese officers, their “wisdom in understanding,” and the “higher side of themselves” which they celebrate here were lost on the allied Prisoners of War they abused, and these qualities will be just as lost on readers of this novel as they read about unconscionable examples of gross inhumanity. Set during World War II, when many Australians became POWs after the Fall of Singapore to the Japanese, the novel details the brutality of the conquerors, their starvation of prisoners, their forcing of dying soldiers to work until they collapsed and expired, their murders and tortures, and even their use of conscious prisoners as guinea pigs for Japanese officers who wanted to test their bayonets. The sadism which paralleled the officers’ interest in poetry was cultivated and celebrated among themselves as proof of their dedication to the Emperor, who could do no wrong. Much of the action here takes place during the building of the Siam to Burma Railway, known as the Death Railway, which the Emperor wanted finished immediately so that it could eventually be extended to India. Over two hundred fifty miles long, and built only with hand tools by sixty thousand prisoners in 1943, the railway paralleled the River Kwai, heading northwest, from Bangkok. Twelve thousand prisoners died during this project, most from overwork and starvation, and some from being beaten to death.

The “sensitivity” of these Japanese officers, their “wisdom in understanding,” and the “higher side of themselves” which they celebrate here were lost on the allied Prisoners of War they abused, and these qualities will be just as lost on readers of this novel as they read about unconscionable examples of gross inhumanity. Set during World War II, when many Australians became POWs after the Fall of Singapore to the Japanese, the novel details the brutality of the conquerors, their starvation of prisoners, their forcing of dying soldiers to work until they collapsed and expired, their murders and tortures, and even their use of conscious prisoners as guinea pigs for Japanese officers who wanted to test their bayonets. The sadism which paralleled the officers’ interest in poetry was cultivated and celebrated among themselves as proof of their dedication to the Emperor, who could do no wrong. Much of the action here takes place during the building of the Siam to Burma Railway, known as the Death Railway, which the Emperor wanted finished immediately so that it could eventually be extended to India. Over two hundred fifty miles long, and built only with hand tools by sixty thousand prisoners in 1943, the railway paralleled the River Kwai, heading northwest, from Bangkok. Twelve thousand prisoners died during this project, most from overwork and starvation, and some from being beaten to death.

Balanced against these horrors, which Flanagan depicts in grim and uncompromising imagery, is a non-traditional love story, which shows aspects of the Australian society from which most of the soldiers have come and hope to return, and particularly the society of Tasmania, which several main characters call home and where author Richard Flanagan himself grew up and has spent most of his life. Dr. Dorrigo Evans, from Cleveland, Tasmania, in the northeast, just south of Launceston, has been raised in a rural area among many people who are still illiterate. As a teenager, he, his brother, and a friend often earn money catching possums on Ben Lomond, sometimes staying overnight in a cave where Dorrigo reads the epic Ulysses to the others by firelight. As the only one in his family to pass the Ability Test for Launceston High School, where he has free schooling, he learns early that he has to fight his way to the top if he is to succeed.

Balanced against these horrors, which Flanagan depicts in grim and uncompromising imagery, is a non-traditional love story, which shows aspects of the Australian society from which most of the soldiers have come and hope to return, and particularly the society of Tasmania, which several main characters call home and where author Richard Flanagan himself grew up and has spent most of his life. Dr. Dorrigo Evans, from Cleveland, Tasmania, in the northeast, just south of Launceston, has been raised in a rural area among many people who are still illiterate. As a teenager, he, his brother, and a friend often earn money catching possums on Ben Lomond, sometimes staying overnight in a cave where Dorrigo reads the epic Ulysses to the others by firelight. As the only one in his family to pass the Ability Test for Launceston High School, where he has free schooling, he learns early that he has to fight his way to the top if he is to succeed.

This picture of possum hunting on Ben Lomond, by John Glover (1767 - 1849) recently sold at Christie's for $2,799,193. Click to enlarge.

Through an impressionistic time frame which circles around and sometimes begins and then abandons characters and ideas, only to return to develop them at a later time, the reader often sees Dorrigo and other important characters at various stages of their lives which do not reflect traditional chronology. From Dorrigo’s teen years, the novel jumps to eighteen years later where we learn that Dorrigo is now a surgeon with a lover. A few pages after this, he is an elderly man suffering from angina and reliving his life. The novel “settles in” to a traditional chronology for much of the novel when we learn that Dorrigo is about to ship out for war in 1943. He participates in the Syrian campaign, fights the Vichy French, and ends up in Singapore, where, along with twenty-two-thousand other Australians, he becomes a POW after the fall of Singapore. From the early pages the reader knows that one-third of these POWs will die, a factor which colors our thinking about the characters here as they work on the Death Railway which they are forced to build for their Japanese captors. Deaths, vividly described, occur faster than the bodies can be buried, and many are simply burned, along with the soldiers’ minimal belongings, on funeral pyres in the jungle.

On Feb. 15, 1942, Gen. Arthur Percival, carrying the British flag in the photo, left, surrenders to Japanese General Tomoyuki Yamashita

Flashbacks refer to various love affairs in which Dorrigo is involved, though he himself, now a surgeon, has always believed that he would eventually marry Ella, the plain daughter of a Melbourne solicitor whom he met in Melbourne during medical school. A visit to a local library changes his life when he meets Amy, an exciting young woman wearing a red camellia in her hair. Thoughts of Ella vanish as he becomes caught up in this relationship, unlike anything else he has ever known. Though he has been committed to Ella – and Amy is married – this love is bigger than anything either has ever known. Without any transitions, the novel then shifts suddenly to conversations among various Japanese officers who are frightened by the decline in food supplies and in medicines for the Railway Command Group. The officers know they must produce the required results for the Emperor, or “they, too, would disappear to their own hell somewhere else on that ever-lengthening railway line of madness.”

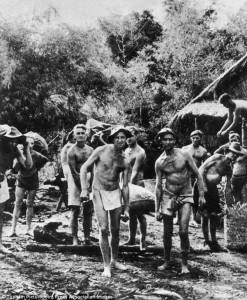

POWs working on the Siam to Burma Railway. These POWs still look reasonably healthy, a condition which changes dramatically when the "Speedo" begins, and they have to work double-shifts.

What makes this novel of warfare so different from so many others with impressionistic structures is that Flanagan creates vibrant scenes which reveal the big ideas and big horrors of warfare and develops some of his repeating characters for fifty years, bringing the story up to the present when his characters are old and providing an unusually broad scope and great depth to his subject matter. About halfway through the novel, the war ends suddenly, with little fanfare, “the dream of a global Japanese empire lost to radioactive dust.” The major Japanese officers return to a defeated country and must learn how to live with defeat. The reader is drawn in as many characters whom the reader will “know” are being sought for prosecution for war crimes. Many make deals in exchange for being let go, leaving lesser men to be prosecuted.

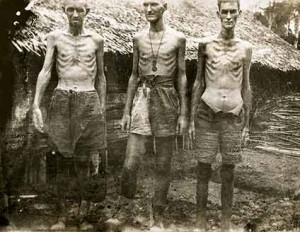

Three prisoners at Shimo Songkurai in 1943. The effects of malnutrition can be seen in their skeletal frames and the stomach of the man on the right, distended by beri beri. The photograph was one of the last to be taken by George Aspinall on the camera he smuggled up to the Thai–Burma railway from Changi. By courtesy of Tim Bowden.

The subsequent lives of the Japanese officers and how they deal with their guilt, are not much different from the lives of the Australian survivors, all of whom feel some level of guilt for having survived. “Neither the Japanese government nor the Americans want to dig up the past,” they understand. Flanagan, who spent twelve years, writing and destroying five complete drafts of this novel before he was satisfied, has created a novel which compels the reader to keep reading for the plot and characters, but also for the political and sociological implications of warfare itself, including nuclear warfare, as a way of imposing change. The novel is big, broad, and deep, a wonderful, though often grim, picture of Australians dealing with the horrors of a war which they did not choose but in which they had to fight for their own futures.

ALSO by Richard Flanagan: GOULD’S BOOK OF FISH and WANTING

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.independent.co.uk

“Possum hunting on Ben Lomond,” by John Glover (1767 – 1849), recently sold at Christie’s for $2,799,193. Dorrigo, his brother, and a friend hunted possum in Tasmania to raise money when they were teenagers. Dorrigo spent evenings reading Ulysses, the epic, to the others by firelight. http://www.christies.com/

In the surrender of Singapore, Feb. 15, 1942, Gen. Arthur Percival, carrying the British flag in the photo, left, surrenders to Japanese General Tomoyuki Yamashita. The Australians in this novel thereby become prisoners of war under the Japanese. http://www.prisonersofeternity.co.uk/

Australian POWs working the Siam-Burma Railway, look in reasonable shape here, but when the “Speedo” occurred, and the men had to work double shifts, they quickly became emaciated from their lack of food and the energy expended. http://www.dailymail.co.uk (Topham Picturepoint Press Association)

The condition of these three POWs shows the effects of malnutrition. The photograph was one of the last to be taken by George Aspinall on the camera he smuggled up to the Thai–Burma railway from Changi. [By courtesy Tim Bowden] http://hellfire-pass.commemoration.gov.au/