“When he thought of his life on the farm, he would always think of those quiet times in the barn; the old man, neck craned, studying it as though seeing it for the first time every time. It seemed to him then that the old man had wanted to pull it deep into himself and he liked to think he had. So he carried the urn into the tack room and cleared a spot on the shelf where bits and bridles and hackamores hung. He set it there….until he could figure out the proper place to scatter the ashes.” – from the Prologue.

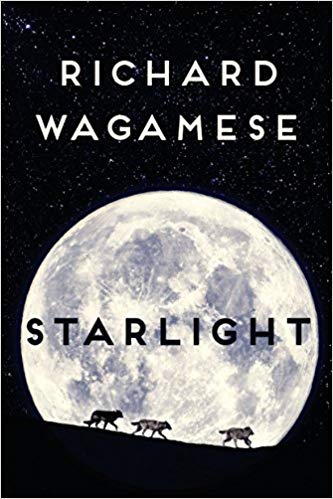

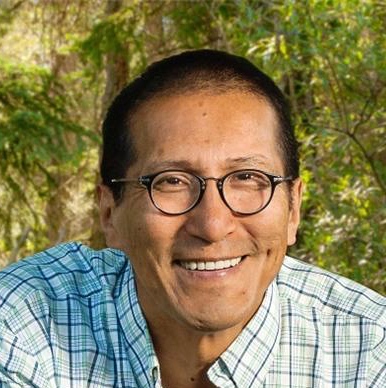

When author Richard Wagamese died on March 10, 2017, Canada lost one of its most articulate and best loved authors. He left behind this nearly finished novel, Starlight. Anyone who has read Wagamese’s other novels will immediately recognize this novel as a grand summing up of the author’s deeply felt relationship with the earth, the animal world, and with all of Nature, and will rejoice with him in the sense of peace and confidence he has found and shared throughout this novel. The end of Wagamese’s life was far different from his beginning. Born an Ojibwe Indian, he and his three siblings were abandoned before he reached the age of three, and his several foster families were often abusive. According to Susan Walker in her essay “Stories that Heal,” in the Literary Review of Canada (March 29, 1017), young Richard ran away for good at age sixteen, lived on the street, abused drugs and alcohol, spent time in jail, and was finally rescued by an older brother when he was twenty-five.

When author Richard Wagamese died on March 10, 2017, Canada lost one of its most articulate and best loved authors. He left behind this nearly finished novel, Starlight. Anyone who has read Wagamese’s other novels will immediately recognize this novel as a grand summing up of the author’s deeply felt relationship with the earth, the animal world, and with all of Nature, and will rejoice with him in the sense of peace and confidence he has found and shared throughout this novel. The end of Wagamese’s life was far different from his beginning. Born an Ojibwe Indian, he and his three siblings were abandoned before he reached the age of three, and his several foster families were often abusive. According to Susan Walker in her essay “Stories that Heal,” in the Literary Review of Canada (March 29, 1017), young Richard ran away for good at age sixteen, lived on the street, abused drugs and alcohol, spent time in jail, and was finally rescued by an older brother when he was twenty-five.

Wagamese is quoted in that same essay by Walker as saying, “I did not speak my first Ojibwa word or set foot on my traditional territory until I was twenty-six. I did not know that I had a family, a history, a culture, a source for spirituality, a cosmology, or a traditional way of living. I had no awareness that I belonged somewhere.” It was his connecting with the past through elders from his tribe that he began to discover a sense of “belonging.” He eventually became a journalist and Native Affairs columnist in Calgary, and later turned to fiction, always working on subjects which allowed him to explore his Native American heritage.

Wagamese is quoted in that same essay by Walker as saying, “I did not speak my first Ojibwa word or set foot on my traditional territory until I was twenty-six. I did not know that I had a family, a history, a culture, a source for spirituality, a cosmology, or a traditional way of living. I had no awareness that I belonged somewhere.” It was his connecting with the past through elders from his tribe that he began to discover a sense of “belonging.” He eventually became a journalist and Native Affairs columnist in Calgary, and later turned to fiction, always working on subjects which allowed him to explore his Native American heritage.

This novel will thrill those who have enjoyed Wagamese’s past novels, even though it is unfinished. Here he dramatically recreates and shares the breath-taking, almost magical, moments in which he becomes one with nature in its grandest sense, and as he teaches a young, abused woman and her child how to feel the pulse of the world and to find peace, he becomes real in ways I have not seen in his previous novels. He becomes a teacher here, sharing what he has learned in his lifetime, without becoming preachy or sentimental, and I found the book’s lack of completion an ironic benefit: He is so good at conveying the essence of what he has learned in his lifetime that the story itself becomes a simple vehicle, rather than an end in itself. For those who prefer an obvious resolution to the narrative, in addition to the clear resolutions to the themes, the publisher has provided “A Note on the Ending,” in which the pre-planned resolution to the narrative is described in general terms, along with an essay by Wagamese entitled, “Finding Father,” which provides parallels between his own life and the ending planned for this book.

As Emmy becomes more attuned with nature, Frank challenges her to touch a wild deer. (Still photo from a YouTube video.)

The action begins in 1980, with a young woman named Emmy skulking in the dark toward a cabin in which she has lived with Jeff Cadotte, a violent and abusive man who is often drunk, and his work partner, the enormous Anderson. Emmy and her six-year-old child Winnie plan to sneak into the house, take their belongings and a bit of food, steal the keys to Cadotte’s truck, and take off while he and Anderson are drunk and unconscious. Unfortunately, Cadottte awakens, and violence results. Though Emmy and Winnie eventually escape in the truck, they are on their own with no money, dependent on siphoning gas for the truck and on breaking into houses for food. She cares, however, feels guilty and embarrassed to do what she is doing to survive, and at one points leaves a thank you note to the woman whose house she has robbed of food and a chocolate cake. While she is escaping into rural territory where she thinks she will not be found, she and Winnie are arrested for stealing at a supermarket. It is only the kindness of Frank Starlight, who happens to be present in the store, that she escapes. He offers her a job as his housekeeper and satisfies the store owner, and eventually the social worker, that he will be responsible for seeing that Winnie go to school and Emmy work to repay what she owes.

Frank Starlight is a photographer of Native American descent, with an uncanny ability to capture images of wild animals, especially wolves, and he is well known among patrons of a gallery in Vancouver for his work. Emmy becomes the perfect housekeeper and cook on his farm, thrilled that he is willing to buy new appliances for his house and for her and Winnie. His friend Roth, a former employee who lives on the premises, is also delighted to have Emmy, and especially little Winnie, in his life, and Winnie, in turn, grows to love him as a father. All four agree that this is the closest any of them have ever felt to having a real home. Camping trips on weekends show Emmy and Winnie learning to ride horses, explore nature, catch fish, find mushrooms, survive on their own, become physically fit, and come to some awareness, for the first time, that personal peace can be achieved by communing with nature. Emmy eventually recognizes that Frank has not just taught her about the land, however. “You were teaching me to listen to myself,” she says, and he admits he was. When he challenges her to use all her newly acquired talents to touch a deer, she accepts the challenge. He later comments,“You touch a deer, you gallop a horse. There’s no room in there for hurt or anger. That’s where you learn and live when you come to the land.”

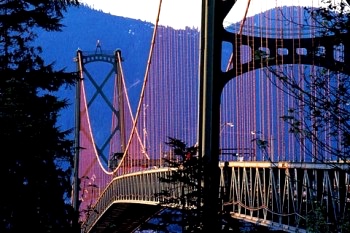

The group crosses into Vancouver via the Lion’s Gate Suspension Bridge on their way to an art show featuring some of Frank’s photographs.

Alternations in the narrative reveal how Cadotte and Anderson have been trying to find and exact revenge on Emmy for her past actions – before Starlight – and their plans finally come near to fruition, but not resolution, near the end of the narrative, an eventuality which the editor and publisher address directly in their notes at the end. Though parts of the novel feel a bit artificial, the novel, overall, is one that I found totally involving, moving, and emotionally satisfying, despite minor quibbles that probably would have been corrected in final editing. This was a novel which pulled together many of the themes which Wagamese has been developing and expanding for his whole career, and I found it, unfinished as it may be, to be his crowning glory.

ALSO by Wagamese, reviewed here: MEDICINE WALK and INDIAN HORSE

Photos: The author’s photo appears on https://edmontonjournal.com/

The wolf photo may be found at https://americanexpedition.us/

Patting a wild deer, a challenge Frank gives to Emmy, is featured on this YouTube video, from which this still photo is taken. https://www.youtube.com/

A herd of wild horses becomes a part of the group’s trip to Vancouver for an art show featuring some of Frank Starlight’s photographs. http://artofliving.summitlodge.com

The group crosses into Vancouver via the Lion’s Gate Suspension Bridge on their way to an art show featuring some of Frank’s photographs. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca