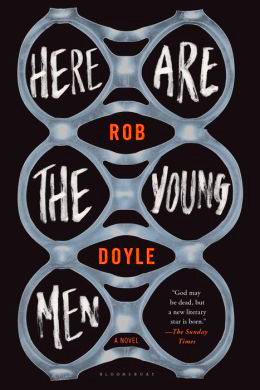

Note: This novel was SHORTLISTED for Best Novel by a Newcomer in the Irish Book Awards for 2014. It was also chosen a BOOK OF THE YEAR by the Irish Times, the Independent, and the Sunday Business Post.

‘What the hell are you goin to do with yer life,’ my da said. ‘I’ll tell you one thing, if ye really did make a balls of your Leavin Cert because ye were too busy dossing and feelin sorry for yourself, ye better not expect us to support ye. …What’ll ye do for the summer? Have ye started looking for a job yet?’

I scowled and said, ‘I just did me last exam yesterday, how could I have had time to find a job?’—Matthew Connelly, age 18

Set in Dublin in 2003, during the height of the Celtic Tiger economic boom, Dubliner Rob Doyle’s debut novel focuses on four young men who have just finished secondary school, none of them with any idea of what they want to do with their lives, and even less motivation. Most have been ignoring the academic demands of their school, preferring to float rootlessly within the social atmosphere of their peers, an atmosphere in which drugs and alcohol have been the primary driving force. Main character Matthew Connelly, a teenage Everyman who sometimes behaves like a punk, does not know whether he has passed his Leaving Certification, and he does want to think about it. He and three friends grow for the reader within their own chapters here, and the comparisons and contrasts in their lives are vividly illustrated. Joseph Kearney, a friend whose whole life seems governed by his consumption of drugs and alcohol, is showing dangerous signs of losing all control. Richard Tooley, “Rez,” a more sensitive and thoughtful character, thinks through his present situation with his friends and makes what he regards as philosophically valid decisions. The fourth teen, Gary Cocker, the least developed, often acts as a foil for the actions of the others.

Set in Dublin in 2003, during the height of the Celtic Tiger economic boom, Dubliner Rob Doyle’s debut novel focuses on four young men who have just finished secondary school, none of them with any idea of what they want to do with their lives, and even less motivation. Most have been ignoring the academic demands of their school, preferring to float rootlessly within the social atmosphere of their peers, an atmosphere in which drugs and alcohol have been the primary driving force. Main character Matthew Connelly, a teenage Everyman who sometimes behaves like a punk, does not know whether he has passed his Leaving Certification, and he does want to think about it. He and three friends grow for the reader within their own chapters here, and the comparisons and contrasts in their lives are vividly illustrated. Joseph Kearney, a friend whose whole life seems governed by his consumption of drugs and alcohol, is showing dangerous signs of losing all control. Richard Tooley, “Rez,” a more sensitive and thoughtful character, thinks through his present situation with his friends and makes what he regards as philosophically valid decisions. The fourth teen, Gary Cocker, the least developed, often acts as a foil for the actions of the others.

With a graduate degree in philosophy, author Rob Doyle writes a novel with simple premises and complex results as he develops his characters, showing how differently they react to their aimless lives. Since this was a period of great economic growth in Ireland, the relationships between the teens and their hard-working parents, who had hoped for success for them, are often understandably frayed. When Matt’s mother asks him what’s wrong and tells him she’s worried, Matthew wishes he could tell them that he “was miserable and could they fix everything, like I was a child still,” but his father, angry and frustrated, cannot help comparing him to his sister, finally exploding, “Do ye not realize how lucky ye are?…Back when I was eighteen, I’d have given me right arm to have what all youse have. But ye don’t lift a finger. Ye just can’t see it, can ye?”

Matt’s parents would have been horrified to know that very close to the time of their talk with Matt about his future, he and his friends, drunk and high on drugs, visited the coastal mansion of U2 singer Bono in Killiney, bent on mischief. Cocker, after announcing on the speakerphone at Bono’s entrance gate that he is Elton John, screams expletive-laden insults at Bono and what he represents for them. Matt and Rez follow suit. When it is Kearney’s turn, however, even his friends are astonished by the unexpected intensity of his foul-mouthed diatribe. He goes way beyond spouting foul language, expressing instead his genuine hatred and announcing that he wants Bono to die.

As the boys wander around Dublin, always drunk and high, they visit popular places like the Temple Bar, Meeting House Square, and the O’Connell Bridge. Like other “normal” teenagers, Matt meets a girlfriend at the Cliffs at Howth, but he also worries about a frightening encounter that Kearney has had with a junkie the previous night. The boys take the DART to Portmarnock Beach on a lovely day, but they also throw stones and other objects at their old school one night. Matt slowly learns about life the hard way, making mistakes, but his heart is good, and he is dramatically affected when he sees a child get hit by a car. Throughout the story of Matt and his growth, the story of Kearney serves as a warning, showing the tenuousness of the boys’ emotional states. A scene in Dublin’s beautiful Garden of Remembrance, followed shortly after by the grand climax at a rave at Greystones Beach, brings the action to its dramatic conclusion.

The eternal generation gap, the unpreparedness of these teenage boys for real life, their seeming lack of values (except for the dubious value they see in each other’s company), and the widespread availability of all kinds of drugs and drink set up these boys for personal failure. Fortunately, some of the boys sense that they must soon “own their own actions” before it is too late. However foreign the worlds of these teenage boys may be to the reader’s own experiences, the author draws the reader into the action by presenting insightful, if disturbing scenes, related in honest, uncompromising language. The boys’ conversations and behavior, while often bizarre, somehow inspire empathy, since most seem to have some residual sense of what is “right.” A motif concerning the surprising suicide of a schoolmate on the last day of school inspires much soul-searching regarding life and death and meaning, though one teen goes so far as to suggest that “people love war and love watching it on the telly, and if we didn’t have wars…we’d all be bored senseless and turn on each other to get our fix of violence.”

Despite all the drugs and alcohol, each character maintains a kind of personal honesty here, even when out of control, making the reader both sympathetic and empathetic. The atmosphere, beginning as it does with the boys’ rude but relatively harmless visit to Bono’s house, which is contrasted with Matt’s fraught talk with his parents at his own house, is tense but emotionally manageable, much like the talks of many other parents with their rebellious teenage sons,. As the novel evolves, and the boys’ own issues become increasingly dramatic, however, the novel becomes darker, more frightening, and eventually violent. Few readers who are drawn in by the action and themes of this novel will be able to forget it quickly, and parents of teens may become particularly alarmed at the unambiguous depiction of their teens’ secret lives.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo, by All Simmons, appears as part of an interview with the author, here: http://irishamerica.com

The entrance to the home of U2’s Bono is the scene of a night-time visit by Matt and his friends. http://hdimagegallery.net/

The famed Temple Bar, adjacent to Meeting House Square, one of Dublin’s most recognizable pubs, drew Matt, Cocker, Kearney, and Rez one evening during the novel. http://www.thetemplebarpub.com/

Portmarnock Beach, visited by Matt and a girlfriend, is one of the most popular summer locales in the Dublin area. http://collegetimes.com/

A scene in The Garden of Remembrance is a turning point of the novel. http://content.wow.com

A rave held at Greystones Beach is the setting for the shocking conclusion of the novel. http://gotireland.com/

ARC: Bloomsbury