“Readers [always] encounter the impossible in vastly dissimilar ways. Some throw the goddam book across the room and curse the author by name. Others imagine the snide comments they’ll post on a book review website…[But] every sane person has to find every day some manner of accommodating the impossible, some way of covering up for the failures of the rational world. This might actually be a reasonable definition of sanity.”

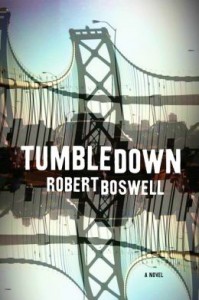

The theme contained in this quotation – that every day a sane person must figure out ways to deal with the impossible – permeates every aspect of this novel by prize-winning author Robert Boswell, whose recent collection of stories, The Heyday of the Insensitive Bastards, deals with similar issues. In Tumbledown, Boswell uses his experience as a psychological counselor to create realistic but damaged characters who try and fail every day to accommodate the impossible. In his dedication to the book, in fact, Boswell honors “all the clients who survived my tenure as a counselor and to the one who didn’t,” an ominous introduction to this novel set in a residential facility, where main character, therapist James Candler, is responsible for six young clients, most of them under the age of twenty-five.

The theme contained in this quotation – that every day a sane person must figure out ways to deal with the impossible – permeates every aspect of this novel by prize-winning author Robert Boswell, whose recent collection of stories, The Heyday of the Insensitive Bastards, deals with similar issues. In Tumbledown, Boswell uses his experience as a psychological counselor to create realistic but damaged characters who try and fail every day to accommodate the impossible. In his dedication to the book, in fact, Boswell honors “all the clients who survived my tenure as a counselor and to the one who didn’t,” an ominous introduction to this novel set in a residential facility, where main character, therapist James Candler, is responsible for six young clients, most of them under the age of twenty-five.

Candler, age thirty-three, is neither a psychologist nor a psychiatrist, and his own life is a mess. He has bought a house outside of San Diego on which he cannot make the payments, and which is now “under water.” He has jumped at the chance to buy a used Porche Boxter which he does not need and cannot afford. He has spent six years living with a woman he thinks he might have loved, but she has left him and has married someone else. Now engaged to a woman with whom his primary contact has been by e-mail, he is also at the mercy of his raging desire for another woman who was once a patient. His only big achievement on the job has been to set up a sheltered workshop for his clients, hoping that they will eventually be able to get jobs on an assembly line. Not at all insightful and frequently patronizing, Candler sticks by the rules and tends to pigeonhole people, not only his clients but the people he knows outside his work. For mysterious reasons, the departing director of the Onyx Springs Rehabilitation and Therapeutic Center has encouraged Candler to apply for the job of director of the facility, and he appears to have the inside track for the job.

A native of Tucson, Candler grew up on the wrong side of the city, the son of two artists, with an older sister Violet, an older brother Pook, who died as a teenager, and a best friend, Billy Atlas, with whom he used to spend hours trading baseball cards and creating an unusual superhero comic strip called Same Man, illustrated by his brother Pook, who made all the faces in the strip the same. Now, almost twenty years later, Candler and his friend Billy are together again – Billy has moved in with him “temporarily” while he takes over Candler’s job of running the sheltered workshop at the Center in anticipation of Candler’s promotion. Billy has never been able to get organized and has spent much of his “career” working at a U-Tote-M convenience store. He has no qualifications at all for the job at Onyx Springs, other than his big heart.

For the first third of the novel, author Boswell introduces his dysfunctional characters, their past histories, and their problems, not just for the clients but the staff, too. Guillermo Mendez resides at the Center hoping that after two tours of duty in Iraq that someone there will declare him unfit to return for another terrifying tour of duty. Alonso Duran disappears into the bathroom so often that Candler has to bribe him to keep him focused on something – anything – else. Karly Hopper, the gorgeous client with whom most of the men, including Billy Atlas, are in love, is mentally handicapped, with an IQ so low she is unable to function her own. She lives “off-campus” with a mysterious, long-distance trucker in his forties, who returns to her place between trips. Bellamy Rhine, a pathetic sort, dreams of Karly, and later of Maura Wood, a tough, smart client who cannot stand him and tells him so. Mick Coury, the client that readers will probably care most about, was a happy, productive teenager until he became the victim of schizophrenia. Stuck, as he sees it, between being a zombie as a result of his medications or being violent and self-destructive without them, Mick agonizes, yearning for the life he remembers from just a few years in the past. Constantly experimenting with his meds in an effort to become closer to “normal,” Mick tries to court Karly, having no clue about her personal life outside the Center and no ability to read the signs or signals she sends.

The Laguna Mountains, photo by mdolly, were a place which client Lowell Darringer yearned to see, similar to his childhood home in the mountains of Montana.

The “plot,” a collection of vignettes involving the characters and their interactions with each other and with life in general, unwinds on several levels at once – sometimes involving scenes of the clients interacting with each other, sometimes clients in conjunction with one or more members of the staff, and sometimes staff members with each other and/or with the two women in James Candler’s off-campus life. The often grotesque ironies in the characters’ lives and their sometimes bizarre interactions, do, at times, lead to scenes bordering on farce, but the overlay of the clients’ dysfunctions and the sympathy these people engender in the reader keep the novel grounded, even when the characters are seriously disturbed. Their irrational behavior represents their best efforts to deal with life’s impossibilities, even when they cannot evaluate their actions in relation to the wider world or see that world for the sometimes absurd, illogical place that it is.

Candler, Lise, and Billy Atlas go to Petco Park, and while there, Lise makes an important confession. Photo by Philkon.

Ultimately, the author summarizes his themes in relation to specific clients and characters in the novel, remarking in the surprising conclusion that “Every reader wants the impossible acts addressed: a big brother’s sudden and permanent and utterly inexplicable disappearance – how is that possible? A son’s baffling descent into madness? A husband who one day cannot lift his coffee cup? A woman who discovers that she has put a price tag on some part of her soul?…” But he then reminds us that “every sane person has to find every day some manner of accommodating the impossible, some way of covering up for the failures of the rational world.” Everybody lives in a “tumbledown” world and there is no going back. “Believing in those days of seamless reality is the real madness,” Robert Boswell says, and the conclusion of this novel, filled with contradictions, impossibilities, and elements of wish fulfillment undeniably proves this.

ALSO by Robert Boswell: THE HEYDAY OF THE INSENSITIVE BASTARDS

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://vimeo.com/

The red Porsche Boxter, which Candler could not resist, appears on http://visualogs.com/

Billy Atlas’s longest job was at the U-Tote-M convenience store, pictured on http://www.dailyyonder.com/

The Laguna Mountains were a place that Lowell Darringer yearned to see, a reminder of his early, lost childhood in the mountains of Montana. Candler promised to take him there. Photo by MDolly on http://www.westcoastwildlife.com/

Candler, Billy Atlas, and Lise Ray attend a baseball game at Petco Stadium in San Diego: http://en.wikipedia.org. Photo by Philkon

ARC: Graywolf