“I’m a poet now, searching for the extraordinary, trying to express it in ordinary, everyday words.”

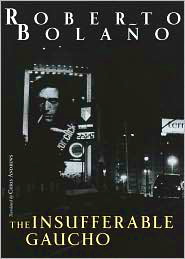

When t he speaker’s friend makes this statement in “Jim,” the first story in this small but unforgettable collection of five stories and two essays by Chilean author Roberto Bolano, the reader cannot help but feel that Jim is in many ways the author’s alterego. Bolano also began his writing life as a poet, something that is obvious in his recognition of the tiny, seemingly insignificant moment or detail which becomes extraordinary within its context. Such “extraordinary” moments or details are worthy of notice, and even wonder, but as the author shows, they are not necessarily “wonderful” in the felicitous definition of the word.

he speaker’s friend makes this statement in “Jim,” the first story in this small but unforgettable collection of five stories and two essays by Chilean author Roberto Bolano, the reader cannot help but feel that Jim is in many ways the author’s alterego. Bolano also began his writing life as a poet, something that is obvious in his recognition of the tiny, seemingly insignificant moment or detail which becomes extraordinary within its context. Such “extraordinary” moments or details are worthy of notice, and even wonder, but as the author shows, they are not necessarily “wonderful” in the felicitous definition of the word.

Extraordinary moments are temporal, and, though meaningful, they can also be shocking or sad. These moments are always succeeded by other extraordinary moments, sometimes seemingly at random–emotionally satisfying moments may be followed by those of devastating shock. For Bolano’s characters, life can be “futile, senseless, ridiculous.” As one speaker comments, “It’s already too late…for everything. Weren’t we damned, right from the origin of our species?”

Throughout these stories, the reader becomes hypnotized by the succession of Bolano’s images, by the lives he depicts (including his own in the two essays), and by the metaphysical suggestions and possible symbols of his stories, despite the fact that Bolano does not make grand pronouncements or create a formal, organized, and ultimately hopeful view of life as other authors do. There is no coherence to our lives, he seems to say: chaos rules. Although artists of all kinds try to make some sense of life, Bolano suggests that their visions may not be accurate since they have no way of knowing or conveying the whole story, the big picture, the inner secrets of life. He himself avoids such suggestions of order in life. Vibrant and imaginative, Bolano’s stories seduce the reader into and coming back to them again and again looking for answers or explanations that often remain tantalizingly out of reach.

Man watching fire-eater in Mexico

“Jim,” which takes place in Mexico, one of the many places the peripatetic Bolano lived, tells of a sad, often desperate man who considers himself a poet, someone the speaker once saw staring rapt, bewitched by a fire-eater, who was performing just for him. “Mexico’s spell had bound him and now he was looking his demons right in the face.” The symbolism is clear, but the story’s conclusion is less so. In “The Insufferable Gaucho,” set in Argentina, where Bolano also lived, an irreproachable lawyer in Buenos Aires is affected by the passage of time and the distancing of his children as they grow up and leave home. Believing that Buenos Aires is “sinking” under its crime, violence, and failed economy, he returns to his dilapidated family ranch on the pampas and tries to restore it and himself. The pampas has also changed, however. “The shame of the nation or the continent has turned [the gauchos] into tame cats. That’s why the cattle have been replaced by rabbits.” Unable to feel at home in the pampas or in the city, the disillusioned Pereda must choose where to spend the rest of his life.

“Police Rat,” the grimmest of the stories, features Pepe the Cop, a rat who describes life in the sewers, even taking time to comment on the non-role of the arts in the lives of rats. The political symbolism and commentary are clear here as Pepe works to capture a murderer, deal with a predatory white snake, and cope with a terrible discovery. “Alvaro Rousselot’s Journey,” set in Argentina, tells of a writer who discovers that his first two books have been plagiarized and turned into films in France. He must decide what this says about Argentine literature and what he should do about his own life as a writer. In “Two Catholic Tales,” Bolano creates parallel stories, telling of a seventeen-year-old boy who is trying to see if he has a vocation for the priesthood, and of a long-time patient at an insane asylum, who describes his terrible experience with priests. The two tales taken together reveal much about Bolano’s view of the extraordinary, what we can never know about extraordinary changes, and whether or not they are random.

Patagonian Mara Hare, the size of a small deer and just as fast. One races to keep pace with a train in a story in this book. Photo by Gabriel Rojo

Two essays at the end are particularly poignant and important for students of Bolano and lovers of literature. “Literature + Illness = Illness,” dedicated to “my friend the hepatologist, Dr. Victor Vargas,” explores the relationship between writing and the illness which would claim Bolano’s life at age fifty, soon after writing this. From the beginning, when the author asks his reader to imagine what it would be like to attend a public event, only to be told that the speaker is ill and cannot appear, the author’s attitudes toward his inevitably fatal disease loom large. At times, he says, writing about his illness is liberating since it offers excuses and inspires compassion, even when the doctor’s news is “unequivocally, spectacularly bad.” He goes on to discuss “Illness and Dionysus,” in which he says, “When people are about to die, all they want to do is f*ck,” then “Illness and Travel,” “Illness and Dead Ends,” Illness and the Documentary,” “Illness and Poetry,” “Illness and Tests,” and ultimately, “Illness and Kafka,” always returning to the idea of the writer and how he regards his work.

Pampas, Argentina

In “the Myths of Cthulhu,” a wonderful companion essay, he comments on Spain’s Arturo Perez-Reverte as the “perfect novelist,” since his work is famous for its “readability.” People enjoy his mysteries because they can be understood. Volunteering that “Latin America was Europe’s mental asylum, just as North America was its factory,” he eventually concludes that “Writers today…are no longer young men of means unafraid to inveigh against the norms of respectable society, much less a bunch of misfits, but [instead] products of the middle and working classes determined to scale the Everest of respectability, hungry for respectability…We are the middle class generation…We think our brain is a marble mausoleum, when in fact it’s a house made of cardboard boxes, a shack stranded between an empty field and an endless dusk…All that carrying on about Proust, all those hours spent examining pages of Joyce suspended on a wire, and the answer was there all along, in the bestseller…Everything suggests there is no way out of this.”

Photos, in order: The photo of Roberto Bolano by Julian Martin, and an article about the “last” interview of Bolano appear on www.guardian.co.uk. A review of the book, Roberto Bolano: The Last Interview by Monica Maristain was published in March, 2010 here: www.guardian.co.uk

A fire-eater with a lone observer, the central image of the story “Jim,” may be found here: http://www.caribbeanfamilytripper.com, image from Paris Parmenter and John Bigley.

The “rabbits” described in the story of “The Insufferable Gaucho” are powerful enough to chase trains, and it is possible that Bolano was thinking about the “mara hare” when he created this image. Native to the pampas, it is the size of a small deer, moves at an extremely high speed, and is capable of making very high jumps. http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/life/Patagonian_Mara. Photo by Gabriel Rojo.

The pampas is shown here: www.destination360.com

ALSO by Roberto Bolano: THE THIRD REICH and WOES OF THE TRUE POLICEMAN