“If you ask me, each of us has two souls, not one, and we take these two souls on our walks. One soul is for the senses, one for the intellect. So, our minds have a soul, which is our point of deepest thinking. And our hearts have a soul, which is our point of deepest feeling. They lead parallel lives, these two souls, never meeting yet connected, and side by side they move into infinity, like legs on a walk.”

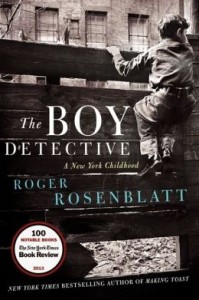

In his memoir of his childhood in the Gramercy Park neighborhood of New York City (18th – 22nd Streets between Park Ave. South and 3rd Ave.), award-winning journalist/essayist Roger Rosenblatt uses the conceit of man’s having separate souls – one for the senses and one for the intellect – as the basis of a memoir about growing up in New York City during the 1950s and afterward. Rosenblatt, now seventy-two, is teaching a course in memoir writing at Stony Brook’s Manhattan campus in February, 2011, when he begins his own memoir. He begins walking the streets he walked as a boy, remembering what businesses used to occupy the premises of various buildings, remembering the people he knew who lived there, and tying his own life as a resident of that specific neighborhood to the many writers and actors who also shared the same neighborhood at different times in history. Delightful, filled with insights into how a “real” writer thinks as he lives his childhood, and thoughtful about how our early lives affect not only our (learned) ways of thinking but also our ways of acting, this memoir is a must for those who love writing, think they might want to become writers, or just want a wonderful, complete reading experience created by a writer who started as a devout reader.

In his memoir of his childhood in the Gramercy Park neighborhood of New York City (18th – 22nd Streets between Park Ave. South and 3rd Ave.), award-winning journalist/essayist Roger Rosenblatt uses the conceit of man’s having separate souls – one for the senses and one for the intellect – as the basis of a memoir about growing up in New York City during the 1950s and afterward. Rosenblatt, now seventy-two, is teaching a course in memoir writing at Stony Brook’s Manhattan campus in February, 2011, when he begins his own memoir. He begins walking the streets he walked as a boy, remembering what businesses used to occupy the premises of various buildings, remembering the people he knew who lived there, and tying his own life as a resident of that specific neighborhood to the many writers and actors who also shared the same neighborhood at different times in history. Delightful, filled with insights into how a “real” writer thinks as he lives his childhood, and thoughtful about how our early lives affect not only our (learned) ways of thinking but also our ways of acting, this memoir is a must for those who love writing, think they might want to become writers, or just want a wonderful, complete reading experience created by a writer who started as a devout reader.

Giving structure and charm to this memoir, he introduces himself as a boy of eight who fancies himself a detective. He regularly trails unsuspecting strangers on the streets near his house, imagining what they are thinking and conjuring the crimes they may have committed. A detective, he explains from his adult/teacher/writer vantage point, “builds his case on hard facts, ballistics and prints, types of weapons, eyewitnesses…and things that are real and really said.” The writer, by contrast, works primarily with feeling, and “the one thing they both require – the writer and detective – is the desire to see what is not there, and to make it at once orderly and beautiful, as in a flower or the answer to a math problem.” The memoir, as it evolves, shows the boy as he deals with these two aspects of humanity within his own life and eventually becomes a reader and lover of detective novels, a writer, and a teacher of writing who has honed his powers of observation and intuition through his constant observations around the city.

When he is very young, the author imagines himself as Edgar Allan Poe, and “I could not help but sense that I was also treading a path that had been laid out before me centuries earlier.” He loves the idea of the “private” detective, since he himself leads a solitary life, with little communication going on at home. His father, a physician, is largely silent and ignores him most of the time, and his mother is so obsessed with taking care of his younger brother that he feels he has much in common with the character created by Jack Douglas in My Brother Was an Only Child. No one seems to care or even notice when he spends hours every day wandering around the city alone, letting his imagination run free, thinking of the Empire State Building as “the city’s favorite uncle who just plants himself in the middle of the house,” and imagining King Kong being told by the “big uncle” that “You can be safe with me.”

As he walks, he decides, “I like living my life without telling anyone,” and he feels intuitively that “I was the world in which I walked.” He believes that “The true walk requires a mind finely balanced between confidence and excitement,” and, in walking, he sees the difference between Europeans and Americans this way: “European explorers return home. American explorers keep walking.” He does realize that “not every tunnel has a light at the end of it,” but as he begins to think about writing, he tries to give some kind of order to his myriad sense impressions and the sometimes invented “memories” coming to him on his walks. He eventually decides that “the best moments of our minds occur at the midway point between poetry and prose…That sweet, solid territory between the two main forms of writing allows for thoughts and feelings not available to each alone…[a place where we can each] tell a tale of high adventure, and sing it, too.”

The young walker haunts the 4th Avenue bookstores, and the proprietors treat him with the respect a developing reader deserves in his explorations within the stores. During his childhood, there were twenty-five such bookstores around lower 4th Avenue; now there are only two left, one of them the Strand, which bills itself as a place with “eighteen miles of books.” In his own house, he climbs the shelves in the library, looking at books as he goes, and when he gets to the top shelf, “I could plant my hand against the ceiling, twelve feet off the ground, and look down on my mother rocking Peter…not even knowing I was in the house.”

Birthplace and museum of Teddy Roosevelt, which the speaker enjoyed visiting with his mother, not far from his own home.

The author tells of his several meetings with former teachers, over the years, and what they have meant to him, and he often addresses his own students within the memoir. At one point he tells a story about a group of children who disappeared without a trace from the private, two-acre Gramercy Park, which his house overlooked. No memorial bench preserves their memories, though sixty years have passed since they disappeared. Then: “That story is made up, as you suspected, but not wholly made up…Here, students, is where fact and fiction meld. And a memoir may make use of either or both.” He goes on to say that he could make up all sorts of ‘facts’ about his family and life, or he “could put it all in a novel, and, believe it or not, in a memoir as well. By the time you’ve told any story, fact or fiction, well enough, you’ve made it up anyway…I do not urge you, or even encourage you, to toss wholesale lies into your memoirs – though not from some ethical compunction on my part, or a fear that you’ll be caught in your lies and pilloried and sued. Rather, that the lies are liable to overtake the facts of your story and run away with it.” Lovers of fine writing will appreciate not only the insights gained from this memoir but the concentrated thought which gives it all relevance and intellectual excitement. Superb.

Note: Here the author is interviewed on PBS by Judy Woodruff:

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Chester Higgins, Jr., appears in the New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/

Gramercy Park (20th and 21st St., at Park S. and 3rd Ave.), the only privately owned park in the city, is two acres, owned by the residents whose houses surround it. Photo by DMadeo. http://en.wikipedia.org

King Kong on the Empire State Building, an image that dominates the author’s imaginative life: http://www.thetimes.co.uk/

The Strand Bookstore, still very much in business, seen here: http://en.wikipedia.org

Teddy Roosevelt’s birthplace and museum, near the house where the author lived, was a favorite place to visit. http://museummonger.wordpress.com/