Note: This review of a novel from 2004, previously published here, is so appropriate in its insights into political movements and the influence of extreme positions, that I am reposting it in the hope that others will be as stunned as I was when I realized how much the author’s insights into life from almost four hundred years ago are applicable to our own lives today.

“From this day forth in this town, there will be no toleration for any crime, error or sin, however slight. Those whose offenses we have too often looked at through the fingers, pretending they did not exist or were nothing but the common sports of Englishmen, such as fornicators, swearers and drunkards, will be punished.”

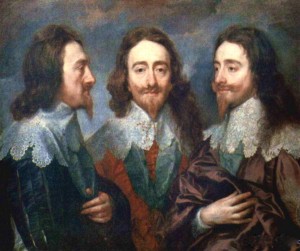

Setting his novel in the north of England in the early 1630s, Irish author Ronan Bennett artfully captures the political, social, and religious turmoil during the reign of King Charles I. Charles, married to a Catholic bride, though England is officially Protestant, has spent his time warring against Spain, and he has committed the cardinal sin—he has lost. He has also been a distant and autocratic king, failing to take into account the enormous religious changes sweeping both Europe and England and undermining his own power. Though England separated from the Catholic Church during the reign of Henry VIII, a hundred years before, grassroots movements wanting stricter accountability for sins have now sprung up, and many local leaders, both religious and civil, are calling for reform and purification.

Setting his novel in the north of England in the early 1630s, Irish author Ronan Bennett artfully captures the political, social, and religious turmoil during the reign of King Charles I. Charles, married to a Catholic bride, though England is officially Protestant, has spent his time warring against Spain, and he has committed the cardinal sin—he has lost. He has also been a distant and autocratic king, failing to take into account the enormous religious changes sweeping both Europe and England and undermining his own power. Though England separated from the Catholic Church during the reign of Henry VIII, a hundred years before, grassroots movements wanting stricter accountability for sins have now sprung up, and many local leaders, both religious and civil, are calling for reform and purification.

John Brigge, a coroner living in the remote northern countryside, has been chosen to be one of twelve reform-minded governors in the area where they live, aiding Nathaniel Challoner, the Master, in his “Revolution of the Saints” and his project to “build a city on the hill,” like John Calvin’s in Geneva. Believing that “in spite of our labors, the people are grown wild,” the Master and his representatives have imposed an even harsher rule than that of Lord Savile, the notoriously callous aristocrat they have replaced, believing that the “sharp law of vengeance” and severe punishments deter other miscreant s from criminal acts. Though he attends the prescribed protestant church, Brigge is in reality one of the “papistical malignants” that the local vicar constantly rails against, a man who must walk the difficult line between the Puritanism of the Master, who is an old friend, and his own Catholicism and the belief that “men must have mercy, for without mercy we are savages.”

s from criminal acts. Though he attends the prescribed protestant church, Brigge is in reality one of the “papistical malignants” that the local vicar constantly rails against, a man who must walk the difficult line between the Puritanism of the Master, who is an old friend, and his own Catholicism and the belief that “men must have mercy, for without mercy we are savages.”

Brigge has been avoiding the town in recent weeks, as his wife is close to delivering the baby they have both longed for and never believed that they would have. Suddenly, he is called to conduct an inquest. An infant has been found dead in a local pub, and Katherine Shay, a Catholic who is deemed “prideful, brazen, and uncontrite,” has been arrested for the murder. Though there is much pressure for Brigge to convict and condemn her immediately, he insists that another woman, who purportedly found the body, be brought to the hearing for questioning. Strangely, she is many miles distant visiting her sister, and the bailiff repeatedly fails to bring her to be interviewed.

While he is in town, Brigge notices that many of the jurymen wear blue threads on their collars and is shocked to discover that these signify their support for Lord Savile, whom Challoner, the Master, has replaced. Convinced, in retrospect, that Savile was less harsh than the current Master and his governors, these men constitute a considerable threat to the Master’s “great project.” Worried that “the better sort” are leaving town because of the high assessments, Challoner cuts taxes by sixty percent, and when one governor points out that this will mean that the poor, who are already near death from starvation, will not then receive their doles, another points out that the Poor Law “is now the mother of idleness. The law should be: he that will not work, let him not eat.” As there is no work, this is a death sentence.

While he is in town, Brigge notices that many of the jurymen wear blue threads on their collars and is shocked to discover that these signify their support for Lord Savile, whom Challoner, the Master, has replaced. Convinced, in retrospect, that Savile was less harsh than the current Master and his governors, these men constitute a considerable threat to the Master’s “great project.” Worried that “the better sort” are leaving town because of the high assessments, Challoner cuts taxes by sixty percent, and when one governor points out that this will mean that the poor, who are already near death from starvation, will not then receive their doles, another points out that the Poor Law “is now the mother of idleness. The law should be: he that will not work, let him not eat.” As there is no work, this is a death sentence.

With numerous subplots and much intrigue, the story of Katherine Shay’s arrest and John Brigge’s search for justice on her behalf evolves. Bringing the period to life on every level of society, the author illustrates in realistic detail the kinds of gruesome punishments meted out for “sins,” the harshness of life for the homeless poor, the dependence of farmers on luck and weather, the fragility of life, the excesses of religious extremism, and the abiding power of love. The realistically presented motivations for some of the extreme behavior in the novel  make the Puritan characters come alive, despite their excesses, while John Brigge, a man who sees more than one side to each issue, becomes a protagonist for whom the reader develops much sympathy.

make the Puritan characters come alive, despite their excesses, while John Brigge, a man who sees more than one side to each issue, becomes a protagonist for whom the reader develops much sympathy.

The language and syntax of the novel have the elegance and formality of biblical passages, filled with observations of the natural world and its harshness, while at the same time revealing the humanity and feeling of the main characters. Though the novel obviously required a great deal of research, the scholarship is so well integrated and so embedded in the writing style that the novel has a unity and integrity rare in historical fiction. The religious symbolism and parallels are unobtrusive during the body of the novel, and despite its somewhat forbidding subject matter, the novel is exciting– full of well-paced action and intense suspense.

The ending, however, is overtly and obviously symbolic. Here the novel becomes didactic, its artistry and elegance subordinated to its message. Some readers may applaud this ending and find it climactic, but others may be disappointed that the thematic balance and restraint which they have observed throughout the novel have been sacrificed at the last moment to an orthodox point of view and conventional conclusion.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.culturenorthernireland.org.

The Anthony van Dyck portrait of King Charles I in three poses (1635) appears here: http://www.wikipaintings.org The King was executed by order of Oliver Cromwell in 1649.

Van Dyck also painted Charles’s queen, Henrietta Maria of France (1637): http://www.historicalportraits.com She died in Paris in 1669.