Note: This novel was WINNER of the Finlandia Prize in 2011.

“There’s a limit to everything. I never hit [my wife] out in the hall of the communal apartment, or in the street, or at the office. I only hit her in our own room, because otherwise the block watch or the militia would show up…Beat your wife with a hammer and you turn her into gold, that’s what the old guys told me… It’s advice I’ve followed. Maybe too much.”—Vadim Nikolayevich Ivanov, “the man.”

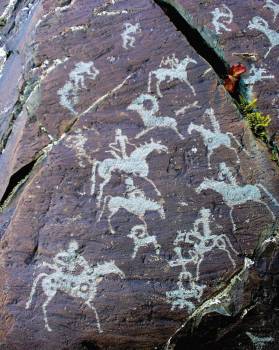

The speaker in this quotation, called “the man” throughout most of this novel, will repel every female reader – and most male readers – with his macho vulgarity, his unrelenting assessment of women in terms of their anatomy and sexual stamina, and his proud alcoholism. Leaving his battered wife behind, he is now on the trans-Siberian train from Moscow to Mongolia for a new job in construction. Though he boasts of his ability to consume seven bottles of vodka a day in his prime, he manages “only” two bottles a day on this trip. Sharing a compartment with him, a character known only as “the girl” had hoped to be alone on this trip. Recovering from a personal crisis involving Mitka, a young friend on whom she had set her romantic sights, the girl is making this trip almost as a memorial to him. She had met him in Moscow in college, where she studied antiquities and anthropology for three years, and they had hoped to go to Mongolia together to see the famous ancient petroglyphs there, some of them dating back to 11,000 B.C. So quiet and repressed that she makes only one or two statements during the entire trip, she is the complete opposite of Vadim, the man, with whom she has been fated to travel.

The speaker in this quotation, called “the man” throughout most of this novel, will repel every female reader – and most male readers – with his macho vulgarity, his unrelenting assessment of women in terms of their anatomy and sexual stamina, and his proud alcoholism. Leaving his battered wife behind, he is now on the trans-Siberian train from Moscow to Mongolia for a new job in construction. Though he boasts of his ability to consume seven bottles of vodka a day in his prime, he manages “only” two bottles a day on this trip. Sharing a compartment with him, a character known only as “the girl” had hoped to be alone on this trip. Recovering from a personal crisis involving Mitka, a young friend on whom she had set her romantic sights, the girl is making this trip almost as a memorial to him. She had met him in Moscow in college, where she studied antiquities and anthropology for three years, and they had hoped to go to Mongolia together to see the famous ancient petroglyphs there, some of them dating back to 11,000 B.C. So quiet and repressed that she makes only one or two statements during the entire trip, she is the complete opposite of Vadim, the man, with whom she has been fated to travel.

The Finnish author of this novel, Rosa Liksom, grew up in Lapland in a village of eight houses, where her family were reindeer breeders. At seventeen she ran off to Helsinki and other cities throughout Europe, living raw, squatting in abandoned buildings and communes, and making her own way, until she began attending college in Moscow, where she decided to study anthropology and social sciences. It is not by accident that the main character here shares the same interest in cultural history and anthropology, and that “the girl” here is also in search of a change of scenery and the beginning of a new life. Liksom, with an extraordinary eye for detail, perhaps honed during her late teen years in which virtually everything she saw and did was a contrast to her life in Lapland, creates vibrant, often lyrical pictures of what might otherwise be monotonous scenery on the girl’s winter train trip to Mongolia. Also an artist, Liksom’s feeling for contrast and color make much of this voyage sound both intriguing and enlightening, despite the bitterly cold, bleak scenery though which they pass.

Readers will cringe at the obscene language that the man, Vadim, uses when he meets the girl, but gradually these two main characters come to a kind of stalemate in which Vadim sometimes makes tea for the girl in the morning, and often offers her vodka, which she refuses. She, in turn, sometimes buys vodka, cigarettes, and food for him when she is killing time in some of the villages through which they stop on their long trip from Moscow to Ulan Bator. The action takes place in the mid-1980s, when the Soviet Union still rules Mongolia, doing everything possible to wipe out the native languages and culture there, and the girl comments that “The terror [still] came and went.” Interestingly, the girl admires – even loves – the Russians and their culture, perhaps reflecting the author’s own attitude after a life of monotony in Lapland.

A grim statue of Dostoyevsky on a grim day in the city where he was a prisoner assigned to a work gang.

Throughout the trip, the girl observes parallels between what she is seeing and what she remembers from some of the many novels and stories she has read by Russian authors. In bleak Omsk, she notes that the city is “sucked dry by the taiga [swampy forests], abandoned by youth…The lifeless copy of a statue of Dostoyevsky in manhood is left behind….A lonely nineteen-storey building in the middle of a field, a five-hundred-kilometre oil pipeline, the yellow flames and black smoke from the oil rigs. Forest, groves of larch and birch forest – these are no longer Omsk.” References to Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, Garshin’s The Scarlet Flower, the work of Pushkin and other literature abound. Music, mostly classical, is broadcast in just about every public park and on the train, from Debussy’s “Afternoon of a Faun,” played in a park in Irkutsk, Siberia’s capital, to Khachaturian’s “Sabre Dance,” played on the train. Louis Armstrong and Dusty Springfield play on the girl’s headphones. Paintings by Ilya Repin – “The Reply of the Zaporoshian Cossacks to Sultan Mehmed” – and one showing Ivan the Terrible with his fatally wounded son – accompany references to Russian history, helping to create a broad cultural background to interest the reader during the characters’ long train trip.

Considering the fact that neither of the main characters is one with whom the reader will identify to any great degree – Vadim because he is so disgustingly venal and the girl because she is so passive – author Liksom does a remarkable job of keeping the reader completely occupied during her novel. Vibrant pictures of life in the Soviet Union from the 1940s to the 1980s emerge as Vadim tells his life story in pieces throughout the trip, and the girl’s own life, though a bit confused and undirected, reflects some of the attitudes of young people and the reasons for her own lack of commitment. Several episodes which take place in the cities where the train stops also add to the atmosphere, especially, in one case, when the girl invites two young men, friends of a friend in Moscow, to visit her. Their fate, directly related to her innocent invitation shocks the reader, illustrating the government’s attitudes at a time in which the weakened Soviet Union is about to break up and become the Russian Federation.

Petroglyphs in Mongolia. These, from 1000 B.C., show the use of horses for hunting. Earlier petroglyphs here date to 11,000 B.C.

The plot, such as it is, consists of loosely organized episodes involving the girl and Vadim, interrupted by passages of romantic, often lyrical descriptions of nature in the winter as the girl looks out the train window. The contrast between the style of these passages, and the bleakness of the landscape helps to define the Russian characters. As the trip ends in Ulan Bator, both the girl and the man have learned from their long trip – “Its joys, sorrows, hope, hopelessness, hate, and perhaps, love,” and, as they head off in different directions, both appear more confident and controlled – he, “going out goating, to get a smell of life and death,” and she, “ready to meet her life, its happiness and unhappiness.”

ALSO by Rosa Liksom: THE COLONEL’S WIFE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Bengt Oberger is from https://commons.wikimedia.org/: His page is here: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

The oil wells and towers, which dominate the landscape near Omsk, are shown here: http://geosferaterrestre.blogspot.com

Dostoevsky was sentenced to a work camp in Omsk and nearly died. He is memorialized there in this statue: http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/

Thousands of children joined the Young Pioneers, sponsored by the Russian Communist Party. Vadim was a member of this group as a child: http://www.atlasobscura.com

Petroglyphs in Mongolia date from 11,000 B.C. The ones shown here are from about 1,000 B.C. and show the use of horses for hunting: http://whc.unesco.org/